Truth is, there is not much an aggrieved business owner can do. Especially when there’s no written contract.

Without resorting to hiring a bunch of debt collectors to knock on doors, you can only have faith that things will get resolved, or just write off the losses altogether and move on.

Unless you take matters into your own hands, as online jewellery shop owner Trixie Khong did last month.

She had only shared her post because she was at her wits’ end.

“In the greater scheme of things, the jewelry we sent to Elaine did not cost a lot of money. I just wanted to warn others that influencers like her and their work ethic could pose problems to our business.”

She adds, “Honestly the post could also have backfired and hurt my business. It was meant for my circle of friends and business owners, that’s why I shared the post on my personal page and not on the official business page. So fortunately the responses were not negative and the problem was resolved quickly after that.”

Trixie’s Facebook post sheds light on an entrenched problem in Singapore that the law hasn’t really been able to mitigate. Since social media influencers became an integral part of digital marketing a few years ago, cases of influencers freeloading and being unprofessional in the work they do for brands are still not uncommon.

The issue is more profound in the business dealings between influencers and small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Unlike the big brands who hire PR agencies to work with influencers on their behalf, smaller companies typically engage influencers directly for convenience and a lower cost.

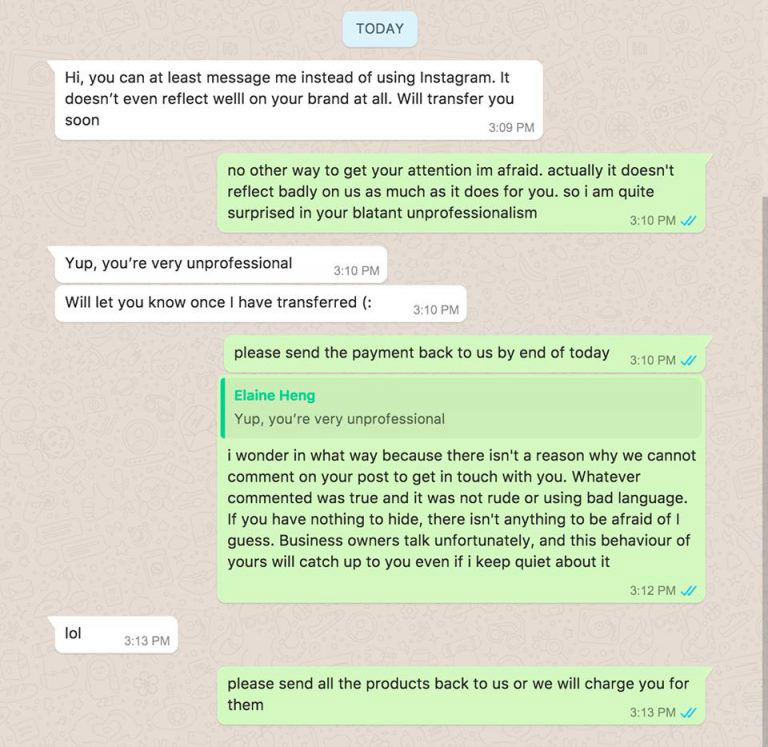

Like Trixie’s case, many of these agreements – whether it’s paid content posts or product sponsorships – are arranged via email or Whatsapp on the pure basis of mutual trust.

Many companies choose not to pursue legal action for fear that taking a hardline stance would also hurt the image of their brand and make it harder for them to work with other influencers.

A contract would also seem intimidating in a partnership where influencers are simply expected to post a mention of a brand on social media in exchange for free product sponsorship.

But pandering to the influencers’ preferences also leaves companies vulnerable to the unprofessional work ethic of those who either procrastinate or, worse still, leech off these brands for free products.

Diving for Pearls, another online jewellery shop, experienced its fair share of trouble when two influencers who had received its products were uncontactable thereafter. With more than 10,000 followers on their Instagram pages, these were no mere amateurs in the business.

Elissa, the company’s founder, says that while those two influencers were under no obligation to post about her products since they were not paid sponsorships, going completely radio-silent was simply unprofessional.

“We usually follow up with these influencers a couple of times. But if they continue to ignore our messages, we will not pursue the matter. We can’t and won’t force anyone to post something they don’t want to post.”

Trixie adds that most of her unpleasant experiences with unprofessionalism comes from working with the top-tier influencers. She acknowledges that these “A-listers” have so much on their plate working with so many brands, often their obligations with smaller companies like hers get de-prioritised.

“There were a few instances when content posts from these influencers were overdue by a few days or even weeks. It can be a headache when they are time-specific posts designed to promote a sales period. When these influencers do finally get back to me, the promotion is already over so what’s the point,” she laughs ironically.

For these brands, influencer marketing is not the only form of advertising that they utilise. But it is still an important way to target specific demographics of consumers, as influencers’ photos create an aesthetic appeal that customers aspire to.

Yet it doesn’t mean that the social media landscape has to be the Wild West where influencers are the modern-day likes of Butch Cassidy and Billy the Kid.

Bryan, a lawyer at Pinsent Masons, cites the Guidelines on Interactive Marketing Communications and Social Media as a form of ground rules that can regulate e-commerce businesses involving influencers. These are industry standards set by the Advertising Standards Authority of Singapore (ASAS), an advisory council under the Consumers Association of Singapore (CASE).

If the trust is broken, business owners can either seek mediation or an action in tort. These tend to be more expensive, however, “so it might be a case of penny-wise, pound-foolish”, says Bryan.

Regardless of the reasons for making business deals over email or text messages, he reiterates the importance of having an agreement inked in black-and-white. Businesses can also seek services which provide legal contract templates for low cost.

Considering that product sponsorships and content posts are not exorbitantly priced, the only practical recourse that business owners have is taking the matter to the Small Claims Tribunal. In reality, as Trixie points out, they may balk at going through all the hassle just for a few thousand dollars (at most).

Legal action tends to be more expensive, so it might be a case of penny-wise, pound-foolish.

Yan, founder of beauty salon Lush Lab, says curating a tight list of influencers gives her a peace of mind as she trusts them to post on social media without the need for her to micromanage.

She admits that as she plans to expand her business, she will definitely have to partner with more influencers which increases the risk of bringing a bad apple onboard.

“Because our customers come for a one-off treatment or service and advertising doesn’t have an immediate impact like the fashion industry, we have to make sure that we work with the right influencers in a long-term relationship so that their posts will have a lasting impact on their followers.”

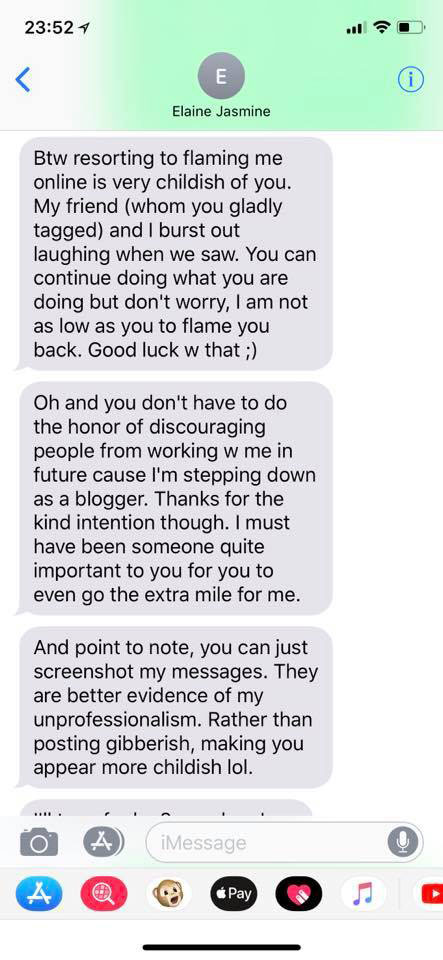

I ask Yan if she would ever resort to sharing an angry post on Facebook if an Elaine Jasmine-type of influencer lands on her boat. Wary of any reputational damage, she laughs and replies that it’s not in the best interests of her and her company to go on a public rant – “I’ve been trained in my previous job at a bank to always resolve disputes amicably.”

Trixie may feel on hindsight that what she did wasn’t the best course of action, but it doesn’t change the fact that it worked. You can win in the court of public opinion, and that should be a grave warning to influencers who think they can get away with cheating, freeloading, or even just being lazy.

Have you experienced problems working with influencers? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co