On June 23rd, twelve boys aged 12-16 and their 21 year old football coach ventured into Tham Luang cave in Chiang Rai Thailand after football practice. Right after that, monsoon rains flooded the cave and trapped the boys deep inside for nine days before they were found and rescued.

One of the most complicated cave rescue missions to date, it took place over a three day period, and involved around 100 divers and about 20 medics.

Upon his return from Thailand, Douglas Yeo, one of the volunteer rescue divers, told me all about his life and what happened in the cave.

As we sat amongst the chaos of lunch hour at Amoy Street food center, leaning over steaming bowls of noodle soup, he recalled the morning he woke up and saw on television the story of the trapped football team.

“At that point in time actually the whole world turned anti-clockwise for me,” he said.

Yeo spoke of that moment as a kind of calling, where suddenly everything turned to Tham Luang cave, and he knew he needed to travel there.

“There’s a lot of how, what, if, when, where,” he added, “All these start to stop you. All of this will slow you down … literally you’ve missed it. Then you wait, for the next train to come. I waited 50 years of my life.”

Afterwards, he shares with me his life’s trajectory to help me understand how fifty years led this incredibly humble Singaporean diver to voluntarily risk his life for twelve young boys.

“I came out to work when I was eight years old,” he tells me, “With my grandfather.”

Before he entered National Service, he lived with his grandfather for six years. As early as when he was attending primary and secondary school, he began to feel responsibility for making money in order to provide for his family. He said his grandfather was his role model, and showed him all of Singapore.

“He treated his people with heart. He would be the last person to eat, the first person to starve,” he said. Yeo would also ride around the island on his bicycle as a young boy, purchasing food and coffee packets from a shop in Clark Quay and selling them to other vendors for small change. This was how he made his livelihood. He would also approach older men in Chinatown and gift them packets of coffee in exchange for their stories, something he still does today. “I learned from working for people,” he said.

Yeo left school at age 16, and began to apply for National Service. But he only attended at age 18. He spoke of the significant effort he put into his service in order to reach the highest placement level, all so he could make enough money to send back to his family to help support his sisters’ education.

“I felt lousy because I didn’t go to school,” he said, “If people do 20, I’m going to do 40.”

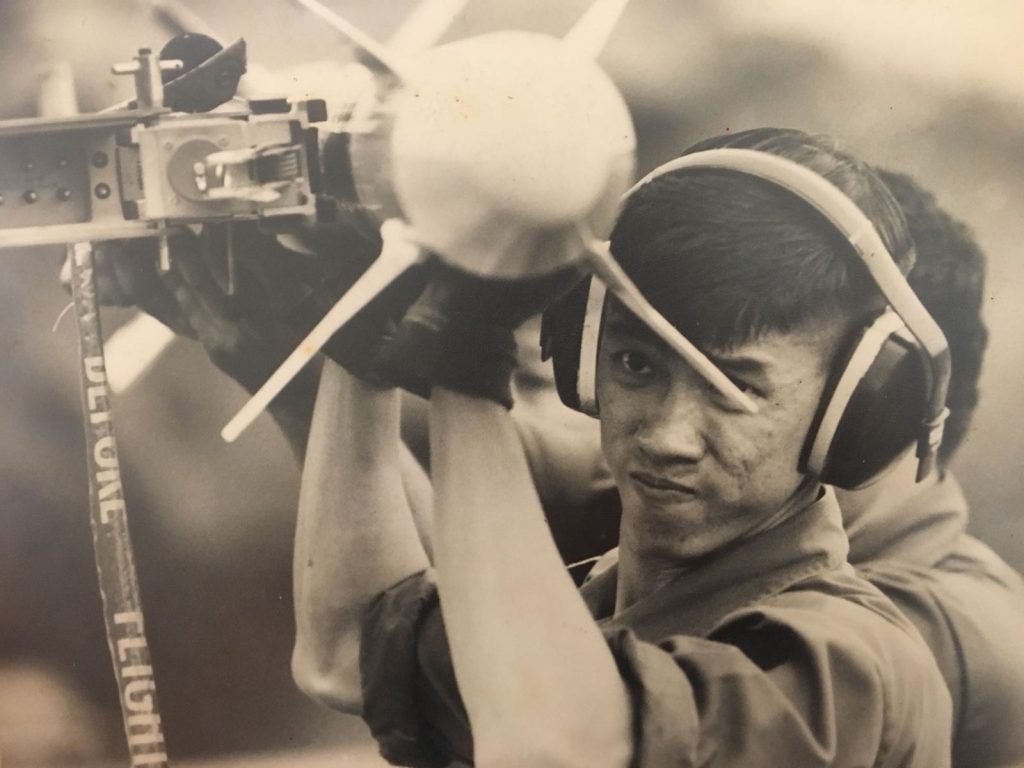

Instead of waiting for his placement after the initial months of training, he walked into the air force and asked for a job, as this branch would promise a more stable and substantial income. He had to be incredibly tough, and physically strong “not because I wanted to be, because I had to be.” With his limited level of education, his hard work ethic and physical strength for his acceptance into the air force.

Despite dedicating this period of his life to the sky, he can still recall the moment he fell in love with the sea.

While still in the air force, Yeo was in Western Australia with a friend who was in the Navy.

“He dressed me up like a merman, and he put me in the water for 45 minutes all by myself,” he said.

He sat at the bottom of the ocean and watched the coral move with the currents. At the same time, Yeo was not in complete solitude. He spoke of realizing how the coral just centimeters from his face was in fact a giant moray eel staring back at him. Yeo fell in love with diving that day, “I think I belong to the ocean,” he said, describing the natural colour and quietness he found underwater.

When he came back to Singapore, Yeo left the force as a highly regarded sergeant, and began saving money by working part time jobs, at least until he could afford the 100 dives that would earn him his certification.

“I found my root, I found my life,” he says.

To make money efficiently, Yeo often worked more dangerous, dirty jobs such as cleaning the bottom of boats.

“It’s all about survival,” he said, “It’s either you make it or you break it. There’s no in between.”

For six years, Yeo also worked as a salvage diver, where he was tasked with rescuing lost or damaged boats, disassembling and hauling pieces of shipwrecks out from the bottom of the ocean, and rescuing people stuck at sea. This job took him to places like Peru and Brazil, and he continued living his life for the benefit and safety of others, putting his own life at risk on a daily basis.

“It is us, it is you and me. We do things sometimes, we don’t know why,” he said, as he came back to the moments before he left to Thailand for the rescue mission.

Like the ocean, Yeo is constantly moving and full of life. He travels to wherever he is needed, even describing a smoothness to which everything occurred after he made his decision to travel to Chiang Rai. Alone, he arrived at the cave entrance and began offering his assistance in any way he could. His preparedness to do anything to earn money as a young boy and in the air force had stuck with him since, and he worked outside of the cave for almost two days, serving water and food to distressed family members and the other hundreds of people waiting by the entrance.

With the little Thai he knew and his obvious physical capabilities, Yeo was eventually brought into chamber two (the boys were trapped in chamber one) by the Thai navy seal in charge.

Once in the cave, it seemed as though the rest of the world stopped existing . His entire focus was on the rescue.

“I even forgot who was my family,” he shares, “My whole focus was my safety. When I’m safe I can save other people. I have to be 101% safe.”

“I held his hand in the dark and asked him, buddy are you okay? … (I said to him) Tell me a little bit about where you live, back home,” Yeo said.

In addition to the extremely low visibility in the cave, verbal communication was incredibly difficult, due to the intensity of the echo. This meant that communication between divers had to be close and clear. Eye contact served as a primary means of communication, and this basic human connection was necessary in order to remain safe and smart throughout the rescue.

With the sensitivity of echo, and low visibility, all communications had to be made in close proximity in order to be clear.

In this day in age, it is uncommon that we find ourselves in a dilemma that technology cannot solve. Yet Tham Luang cave, being incredibly dynamic, made the use of a drill or a submarine impossible.

The discomfort divers and volunteers experienced in the cave was not only environment related, however, as he describes a very prevalent spiritual presence.

“There are other spiritual things moving around,” he said, “There can be animals, there can be soul, there can be the universe… and when you start to feel these kinds of things it’s a good sign. It’s not scary … they are there to help. Nature you cannot control, like the water flow, they will help. When it’s cold, they will give you a little bit of warmth.”

All his life, not only has Yeo been completely attuned to the needs of other people, he has also conveyed a deep connection to his surrounding world. From his school days of skipping classes and running to catch bugs and find fruit, to his many years of loving the ocean, Yeo expressed a deep appreciation for nature from the very beginning. Although dedicating his life to the world of diving, where one learns how to manipulate the laws of nature and breathe underwater, it is almost as if he has always allowed the natural world to guide him.

“I like to help people, I like to talk to strangers, to make sure they’re okay,” he said, “That’s very me…. connecting to nature.”

“How do I explain this?” he said. When Yeo arrived back from the rescue mission in Thailand, however, his wife had thrown the flower away. She said it died while he was gone.

“What made you keep this flower?” he asked himself, “It’s just a flower.”

He shares this story as he spoke of returning after the cave rescue: “That makes me feel like I should come back to what I am and live my life.”

Like the never-ending flow of the ocean, Yeo expressed the need to keep moving from one moment to the next, “Everything in life that will come, will stop. Happiness, sadness, grumpiness. Everything has to come to a stop. Of course, the feeling is still there about the whole mission. But I have to put myself together and say look, my life has to go on.”

For Yeo, diving has been all about sharing something beautiful with the rest of the world. As we finished our conversation over coffee, he maintained the same belief for his story. After many days of fear, discomfort, and unknowing, the cave rescue is an experience he will keep with him forever, but it is one he wishes to share with the world as well.

People all over the world were invested in the Thai cave rescue story, and people seemed to hold their breath until the day the twelve boys were finally brought out from the dark.

“This trip is not about fame, it’s not about glamour. It’s empty. It’s a heart that’s empty,” he says.

“I go down there and I come back and I feel my heart is filled with a lot of love … It’s love. There’s so much of it.”