As I prepare to leave the United Kingdom, deciding which parts of my life at the University of Oxford to take with me in my suitcase, it occurs to me that I am running away. Running home, you may say. Ever since an advisory was issued to overseas students last Wednesday, 17 March, it became clear that this was an evacuation amidst a public, and a global health emergency. One day later, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was working with Singapore Airlines to book students on flights, with “a special rate for travel due to the extraordinary circumstances”.

At any other time, this would be taken as a fantastic deal, but the same web form makes it clear that Singapore Airlines could contact passengers within twenty-four hours of a flight, and could “rebook your travel on an alternative flight due to operational contingencies”. Within less than forty-eight hours, Singaporean students who had resolved earlier to stay and ride out the epidemic, were mostly booked on flights home. Later on, Singapore Airlines would announce that it would cancel all flights to and from London in April, one of its most highly prized sectors.

Being a Singaporean abroad, I’ve always held the assumption that the world could be as safe as home. Bushfires? Anti-Brexit protests? Floods? A plague? I would be careful, and plan ahead; keeping updated and acting quickly where necessary. These time-tested, much-celebrated “national” characteristics would keep me one step ahead. This is, of course, arrogance, because living in a foreign place, even one as international as the University of Oxford, is to throw your lot in with a whole slew of attitudes towards Covid-19.

The University was quick to denounce coronavirus-related xenophobia and violence, such as the well-publicised attack on a Singaporean student in London—in fact, I have not personally experienced any. What was more worrying was the sheer inability of many to recognise Covid-19 as a public health threat. This post from the Oxfess Facebook page, short for Oxford confessions, provides an illustration.

There was intense speculation about the college of the student (Oxford University consists of 39 separate colleges), the dangers of asymptomatic transmission, and how proactive or effective the university was at safeguarding our well-being. In colleges, students interact at close quarters in shared accommodation, and balls and bops were scheduled for the end of term, where hundreds of young, enthusiastic people jive to very good music, helped along by gallons of not-so-good alcohol.

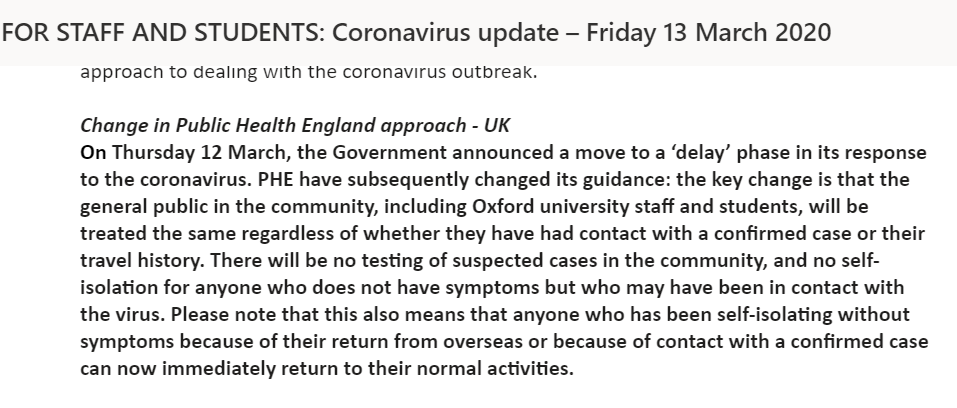

Understandably, the University was hampered by policies from Public Health England. Among its more alarming announcements was one issued on 13 March, after the UK government announced they were moving from the containment to delay phase.

It said: “the key change is that the general public in the community, including Oxford university staff and students, will be treated the same regardless of whether they have had contact with a confirmed case or their travel history. There will be no testing of suspected cases in the community, and no self-isolation for anyone who does not have symptoms but who may have been in contact with the virus. Please note that this also means that anyone who has been self-isolating without symptoms because of their return from overseas or because of contact with a confirmed case can now immediately return to their normal activities.”

For students with respiratory conditions and underlying health conditions, as well as students from Singapore, and other countries like Taiwan and Hong Kong which had experienced SARS, this sounded like a nightmare waiting to happen.

In those two days (10-12 March), there was still an unspoken expectation to show up for official events, worsened by a continued and insensitive insistence that Covid-19 only affects the elderly. We know now this is not true, and on 11 March, the World Health Organisation declared the coronavirus outbreak to be a pandemic. Thankfully by the end of the week, most colleges had cancelled mass events, and were actively persuading all UK-based students to return home for the Easter vacation to reduce the population density. Later, the UK admitted that its much vaunted strategy of building herd immunity was mistaken.

On hindsight, what I experienced in Oxford reflects in miniature, the politics of Covid-19 reporting in the world at large. As an international student, my perspective is always in-between two worlds, and as I go about my day along Broad Street or in the Bodleian, Singapore’s ongoing battle with the coronavirus was always on my mind. For Chinese, South Korean, Japanese, and, as the situation rapidly escalated, Italian students as well, watching the UK sit on its hands was like being doomed with the gift of foresight, but unable to act.

Such nationalist and regionalist perspectives seem self-concerned and smug, in a way that is curiously similar to panic-buying and the hoarding of toilet paper. While there is much to be proud of in Singapore’s early success in containing the first wave of community transmissions, this is a war where we must live with a fragile but important dream—that one day, all countries will be able to open their borders again, and that trade and travel will resume; that we will meet again, laughing and talking freely, face to face.

As the UK goes into lockdown, spring is just beginning here in Oxford, and its many gardens and college grounds are full of blossoming trees. But the University has mostly closed, and its great libraries and ancient halls are empty. Unlike previous years, there will be no Trinity term (all learning has moved online), with its garden parties, its outdoor plays, and graduation ceremonies, where the bell at University Church tolls once for each newly gowned student, surrounded by friends and proud family members. Despite the few days of intense uncertainty, Oxford’s colleges have provided the best care possible, while operating under prevailing conditions. International students who could not return home due to Covid-19 were given financial aid to stay, and college staff were working round the clock, even remotely, to provide day-by-day guidance on the fast-evolving situation. And Oxford’s researchers are doing what they are best at, by developing a rapid testing kit for the virus.

There is a way in which Covid-19 news can reduce us all to data: just case 236 or someone’s else statistic, or a little bit of drama in yesterday’s newsfeed. That doesn’t have to happen. The last thing we should run away from is being kind.

As I count down the hours to my flight, which hopefully will not be cancelled again, I feel sure that I will be back. There are many books that I’m leaving behind, and a bird-feeder. Living with covid-19 in Oxford has led to anger, fear, and much anxiety in the early days. In fact, it has only been two and a half weeks. But despite it all, or because of it all, I am finding a new calm and intentionality—one where going on with my Oxford work in Singapore is definitely not running away.