You may have heard the common refrain that the music and films people consume can speak volumes about their identity. But what about the destinations that they’ve logged on a ride-hailing app?

Can a person’s Grab booking history or the various ways they engage with the app offer us equally intimate insights into who they are—beyond their manicured Instagram feeds—in the way that Spotify playlists or Netflix viewing patterns can?

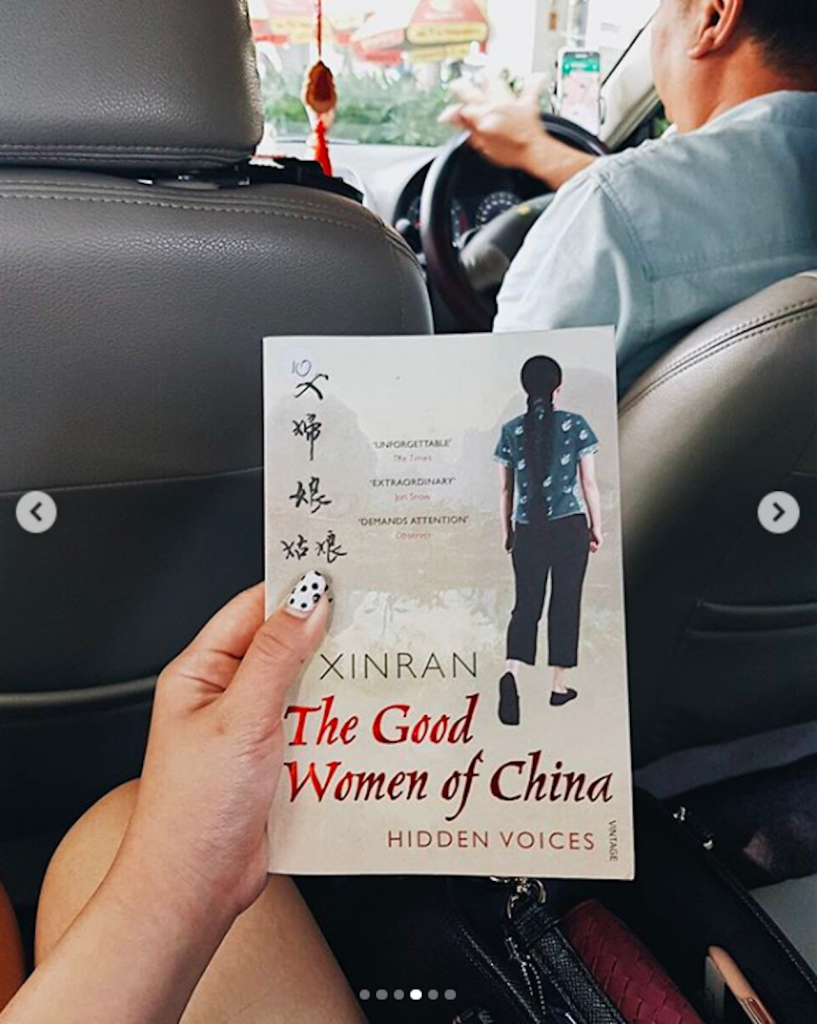

This thought crosses my mind after a tearful Grab ride home during a stressful week. As my driver zoomed down the PIE, street lights casting half shadows on my face while the light from my phone illuminated everything else, I realised my transport journeys have rarely been about getting from one point to another.

In the bubble of the backseat, every Grab ride becomes my momentary reprieve from reality; every location stored in the app represents a version of myself I present to the world.

Work: stoic, perfectionist, fine.

Home: drained, unguarded, free.

As a passenger who uses Grab when I’m in a rush or feeling stressed, I admit I’m often less empathetic to drivers than I should be. At the same time, my rides have always provided me with a sense of escapism precisely because I’ve been lucky enough to have drivers who get me to my location without hassle.

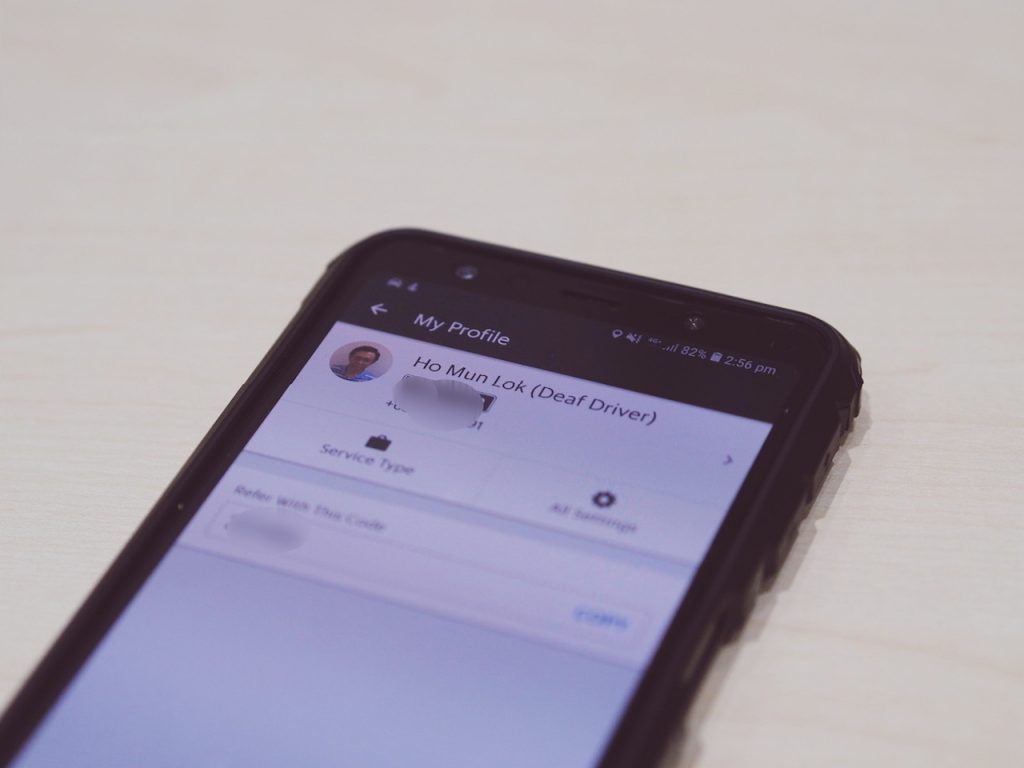

After he gets off work at his full-time job as an architecture assistant, 51-year-old Mr Ho drives from 6 PM to around 2 AM. He does this six days a week.

He’s the sole breadwinner of his family of four; his wife doesn’t work and he has two children—one in nursery school and the other still a baby. Being a driver with Grab provides him with the necessary side income because he doesn’t earn enough from his day job.

Though most passengers don’t have any issue with his lack of hearing, Mr Ho admits that the older generation should “trust deaf drivers more”. As it is, they believe deaf drivers are less safe, though he explains that his hearing aid actually helps him to pick up on environmental sounds.

Deaf drivers also tend to have a heightened visual sense since they can’t hear, he tells me. This makes them extra alert when it comes to remembering road names and looking out for blind spots.

Yet perhaps the biggest ‘issue’ deaf drivers face has nothing to do with hearing or communication. When some passengers find out Mr Ho is deaf, they try to tip him out of good will, though he doesn’t feel like he should take their money. He understands their intentions, but maintains that he’s “just a driver like anyone else”, and doesn’t need pity.

It means ‘thank you’ in signed language—as a placard at the back of his passenger seat has taught me.

On the other hand, I empathise with how fellow writer, high achiever, and insane morning person Jemimah Wei uses the app to maximise time amidst her busy schedule. Both of us usually start our days at 5 AM. She leaves for the gym at 5:50 AM and arrives around 6:20 AM, in time for a 6:30 AM class. After class, she showers and gets to the office by 8 AM, where she reads for an hour before doing most of her serious work.

Admittedly, this self-imposed discipline and laser-sharp focus is partly possible because she can Grab to the gym in the morning, allowing her to begin the day with a clear head. Yet she reiterates that Grab is a financial commitment that she’s privileged to even have.

“Some time ago, it became obvious that given my workload and the limits of what I’m humanly capable of doing, I had to start looking at how to maximise my time and incorporate more rest into my day,” she says.

“The trigger was having to teach morning classes in NTU, which is across the island from where I live. It takes two hours for me to get to the university via public transport, which means I would have to be up at 6 AM for a 9 AM class.”

She adds, “When I’m not sleeping, I’ll listen to podcasts or read, but most of the time I’m knocked out cold. A lot of my work requires me to perform public exuberance constantly, especially screen work, which requires very high energy levels. So I really appreciate having a little air-conditioned bubble to be quiet and unwind.”

Unlike Jemimah, however, I am not as disciplined. Often, I simply pray that life doesn’t put me on edge so often that I need to seek comfort in the privacy of a Grab car’s backseat just to breathe.

Danial has muscular dystrophy, a condition that made him a wheelchair user at 15. He was both “fortunate and unfortunate” to remain in a mainstream secondary school, because his then Vice Principal wanted to help him adjust to the school’s facilities. At the same time, he realised that his school wasn’t built for a wheelchair user; there were no handicapped toilets or lifts, so he had to use the staff toilets and his classrooms had to be on the first or second floor. (The school had a ramp leading to the second floor.)

“If I want to take myself or my girlfriend somewhere that’s not friendly for wheelchair users, I need to prepare myself. It’s not as easy as just jumping over a pond. But I’d say 85% of Singapore is wheelchair user-friendly. The remaining 15% are bars and clubs.”

“Fancy, nice places,” he adds.

“With Grab, I don’t have to flag a cab because that requires me to go to the main road. Getting into a cab at the main road holds up other road users. Regular people can jump into a cab in two seconds, but being in a wheelchair takes me about 25 seconds to properly put the wheelchair in the boot,” he explains.

Moreover, Danial doesn’t like handling cash in a cab, because his “fingers don’t work” due to his condition. With GrabPay, he is able to skip the inconvenience entirely.

He’s also noticed that there are younger Grab drivers who speak English, which makes it easier to instruct them on how to dismantle his wheelchair properly.

While Danial doesn’t believe Grab drivers should necessarily be trained by Grab to know how to interact with wheelchair users, he hopes the app can make it easier for persons with disability to alert drivers to their disability. Currently, users manually describe their disability, from blindness to being in a wheelchair, in the option box.

Talking to Danial makes me starkly aware of the immensely ordinary tasks I’d taken for granted, more so after he offers me a cigarette. With his hands clasped around the packet, he raises it to his mouth. Then he pulls out a cigarette with his teeth. Holding his lighter between his knees, he bends down, puts his cigarette to lighter, and brushes his hand against the lighter several times to light his cigarette.

In comparison, it takes me three seconds to retrieve a cigarette from the box and light it.

“I wanted to place myself in an industry where I’m not defined by my disability. In music, I’m not physically lacking in any aspect. For example, there’s no such thing as wheelchair jazz; it’s just jazz or not jazz,” he says.

“I’ve learnt to see my wheelchair as a privilege. If I wasn’t in one, I would be way too easily content, and I wouldn’t push myself to achieve more.”

Thrown together in the enclosed space of a 30-minute Grab ride, I learn more about life than I have in a long time, from a man who was barely a stranger an hour ago revealing the gravity of his gratitude.

While waiting for my driver, I scroll through social media and clear my emails. The ride-hailing app hums away in the background—a cursory yet vital glimpse into an exhausting yet well-lived life.