Ask anyone to recite a Chinese idiom, and nine out of 10 answers would probably be 风和日丽.

Literally translated as “a fine sunny day with moderate wind”, it comprises four easy words to remember, and has a nice ring to it.

It has been so popular as the default opening to any Chinese essay (as long as it wasn’t raining in the story’s setting) that it’s now a national icon. You find it printed on Singapore heritage-inspired memorabilia, and even as a large decoration at a Southeast Asian-themed rooftop bar in town.

I’m surprised it has not been used as a title for a Mediacorp Channel 8 show yet.

The ubiquitous use of the Chinese phrase is so profound that it has since become a running joke to make fun of not just Singaporeans who did not master their Mother Tongue (like my colleague), but the rote learning that has become entrenched in Singapore’s education system.

After all, we were taught to memorise a thousand and one things in school, and yet 风和日丽 has still stuck with us all this time.

“We tell students that they do not need to spend too much time on their intro. So 风和日丽 is sufficient. Even a P1 kid can handle this phrase,” she says.

If 风和日丽 gets a free pass even though it’s so passé and overused, then it sounds like the emphasis on writing has been superseded by other aspects of Chinese education.

In fact, over the last few years, the structure of the mother tongue syllabus has been heavily overhauled.

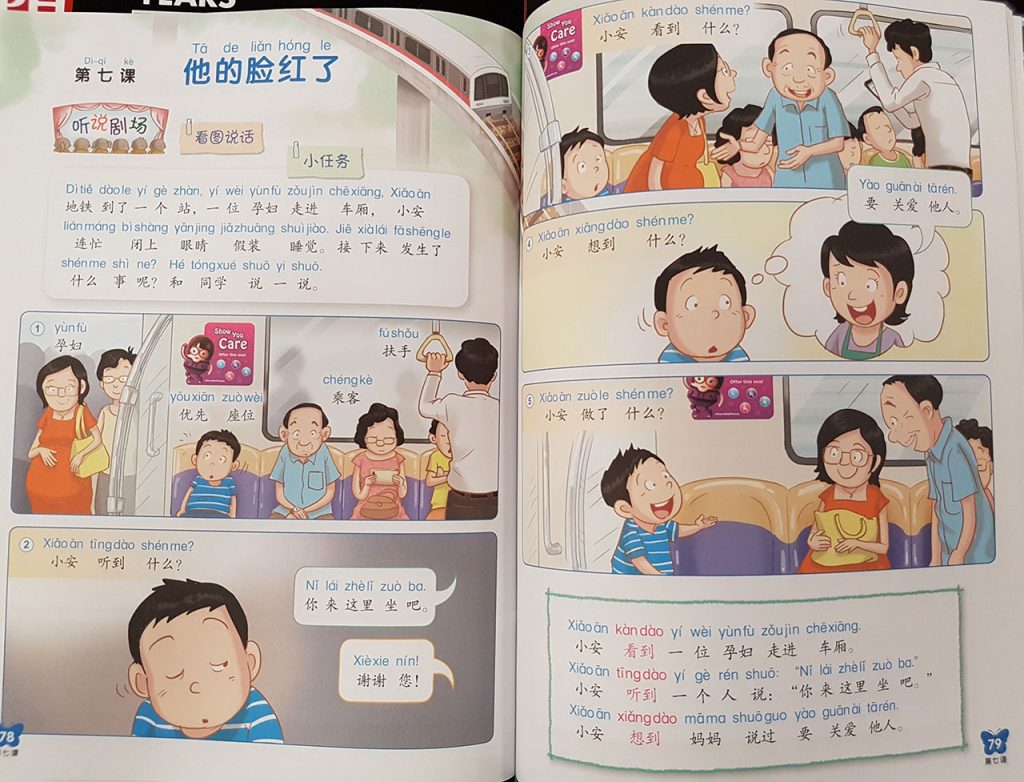

The major changes can be seen in the revamp of the Chinese textbook, which has been taking place progressively each year (the P4 textbook was revised this year). More emphasis is now placed on the oral and listening components – I was astounded to find in the P4 textbook several chapters that featured full hanyu pinyin (romanisation of Chinese pronunciation) to supplement the text.

This is something that was certainly unseen and unheard of in the classrooms of the past.

Yet, the styles of teaching Chinese still varies across different primary schools, and this can have an effect on students’ performance. “Some schools like ACS even use a bilingual approach by printing English words on Chinese worksheets. It all depends on the learning outcomes that each school aims to achieve,” shares Bei Jin.

Conventional teaching methods, like using sentence construction, are designed to help with students’ retention of Chinese vocabulary and phrases without having to resort to pure memorisation. This enables them to use words more flexibly and in the appropriate contexts.

But there is no one-size-fits-all blueprint for educational success. For students with a weak foundation, traditional rote learning methods still offer some form of reassurance, through memorising stock phrases and words. They may not be able to use sophisticated language, but hopefully they can draw upon a more extensive list of vocabulary to supplement simple sentences.

Then there are students who simply have no interest in studying the subject or speaking Mandarin, and neither teaching method would stand a chance of getting through to them.

“A language is first listened to, heard and then spoken. It’s not read or written – that follows later. [But] we started the wrong way. We insisted on spelling and dictation [in Chinese],” he said in 2009.

But the biggest challenge to mastering Chinese still remains – it’s not widely spoken in most households. Even students who come from families that speak Chinese predominantly do not necessarily have a stronger command of their mother tongue, as their vocabulary would still be severely limited to just colloquial use of Mandarin if they do not read widely.

So while building a more organic interest and understanding of Chinese is important, there is still no escaping rote learning simply because of the uneven exposure to both English and Chinese in an enforced bilingual education system.

Most of the changes to the English curriculum come with the implementation of Stellar (Strategies for English Language Learning and Reading) across all primary schools in 2009, to develop students’ ability to speak clearly and confidently.

No textbooks are used; instead storytelling and role-playing are incorporated into regular lessons. This marks a shift away from the old ways of learning English, which comprised drilling exercises and memorising idioms, to equipping pupils with thinking and communication skills.

“In the past, we used to do exercise after exercise on grammar and these were separate from reading and oral components in class. But now we use a story to teach both vocabulary and grammar,” says Sabrina, who teaches English at a primary school in Woodlands.

She adds that teachers must accept that there are no right or wrong answers when students form descriptions in their own words, and it is their duty to provide them with an extensive range of vocabulary that they can tap on to express their creativity.

“Exposure is necessary and sometimes we have to get kids to memorise, if not they will never use the ‘creative’ vocabulary taught to them and resort to using very clichéd and easy-to-memorise phrases.”

However, this is also when you get run-of-the-mill essay introductions like “I glanced out of the window and felt the cool breeze on my neck. The pale sunlight filtered through the majestic trees while the magnolia clouds floated freely in the sky …” as this writer puts it in his commentary for The Straits Times.

He is right when he says that certain aspects of English, like descriptive vocabulary, are meant to be flexible and cannot be taught rigidly. But at the same time, grammar drills are no less important in a creative syllabus – the only way to learn is to practise repeatedly and learn from your mistakes. I still have friends who mix up “its” and “it’s”.

Ruth, who has been teaching secondary school English for 30 years, says, “Teaching languages can be creative, even if rote learning is incorporated, as long as the language progresses to become meaningful. It’s time consuming and we may not see the actual assimilation of the language.

“But every now and then, the students surprise themselves by remembering what they had memorised and then realising that it works.”