Top image: Zat/Rice Media File Photos

“We had all gone to Daiso, picked up white t-shirts and then tie-dyed them pink,” 36-year-old Jess, a lesbian woman, recalls her first time going to Pink Dot in 2009. Although many years have since passed, Jess’ vivid recollection of the day genuinely surprised me. I reckon meaningful moments can do that to you.

“We were also trying to identify or associate anyone that wore pink as an ally. Once we got off at Clarke Quay MRT Station, you could see a few sheepish groups of people. It was like the blind leading the blind but also feeling this immediate connection to these strangers.”

ADVERTISEMENT

As someone who was also there at Pink Dot’s premiere at Speakers’ Corner some 13 years ago, I can attest that till today, I’m still guilty of sneaking knowing looks to people alighting at Clarke Quay MRT station, marching their way down to Hong Lim Park, ready to stand at attention in the name of freedom to love.

Today, the annual Pink Dot event Singapore has come to love and hate in equal fervour looks nothing like it did when it was first held, back when weather and tempers were much cooler and measured.

Then, the word “Dot” is a literal semantic interpretation of the meaning—a small circle. Made by rounding up participants with a rope, it would be safe to say that many of us first-time attendees had no inkling of what this dot would look like. Nor was anyone cognizant of the kind of impact this small, almost haphazardly put-together event would have on how Singapore would approach the greater dialogue of inclusivity amongst the LGBTQ+ community.

50-year-old Shen Tan, a well-loved chef and a gay woman, remembers the first Pink Dot as being “Gay-Lite”. “It’s not like Mardi Gras—it’s not super gay. It’s, well, Mardi Gras-lite. There were lots of kids and lots of families. I thought that was very clever, that it’s not so in your face and not so threatening,” Tan recalls.

“Strategically, it’s what we needed to do. To show that we have hopes and aspirations, family, and love each other—that’s it. We’re not so different from everybody else.”

“It was just so gay.”

As someone who was there as a volunteer for the first iteration, I can safely say that for most of the attendants then, their reasons for showing up were a healthy blend of curiosity and a commendable spirit of activism.

ADVERTISEMENT

Tan remembers wondering how the committee would get Pink Dot off the ground. She first knew of the event after a screening of the movie Milk at Lido. “It was just so gay,” Tan emphasises as we both break into laughter at how incredibly accurate that description was.

“Yes, it’s a seminal gay moment, but I lived in a time when the beach at Tanjung Rhu where gay men hung out got raided and where gay men got entrapped. I was cynical—how would they ever pull it off?

“But when I went,” Tan continued, “we had a great time. It was very chill. It’s essentially a picnic with no political statements. And I remember it wasn’t just gay ppl who went—there were gay allies too.”

For me, my fondest recollection of Pink Dot was the party hats we wore though now, looking back, I’m not sure why we had them on. It’s probably to distinguish the volunteers from the participants.

Those hats were shiny, kitsch, and so incredibly extra. But could anything more aptly capture the guerilla spirit of Singapore’s first pride protest?

A gentle push towards inclusivity

“There were probably 4-5 small booths where people sold various items,” Jess recounted. “There was also an awkwardness amongst groups who recognised each other but didn’t know they were from or supportive of the LGBTQ+ community.”

Jess went on to share that Pink Dot then was a nice and gentle introduction to see how open everyone was to the idea of something like this happening—and in Singapore at that.

38-year-old Fitri, a gay man working in the legal industry, concurs. “It wasn’t sold as something political. It was just an act to show freedom to love. It came at a very gentle angle.”

Still, for Fitri, Pink Dot held a deeper and more life-changing meaning. As a 24-year-old undergrad then, Fitri remembers that time when he struggled deeply with his sexual identity.

To better understand his feelings, Fitri decided to join a support group at Oogachaga, Singapore’s first community-based counselling, support, and personal development agency for LGBTQ+ individuals, couples, and families.

“In the support group, one of the participants involved in Pink Dot asked us all to go and participate,” Fitri reminisced.

“By then, I’ve done the work and finally felt comfortable with myself and my sexual identity. I’ve already come out to myself, and I thought attending Pink Dot would be a good next step—like a powerful statement.”

Pink Dot 2013 was also where Fitri met his current partner. That year, Fitri attended Pink Dot amidst a series of personal life challenges—he wasn’t in the right headspace to attend. “Initially, I didn’t want to go, but when I was there, I met him, and he was flirting with me. *Laughs* It’s a Pink Dot love story!”

Of progress, criticisms, and controversies

As a social movement, Pink Dot’s evolution has been a grand exercise of making lemonades, fruit punch, gin and tonic, teh-si, and bubble tea when life throws you lemon after lemon after damn lemon.

ADVERTISEMENT

Attendance-wise, Pink Dot’s efforts have been stellar, growing from a cosy 2,500 in 2009 to an eye-popping 28,000 in 2015, crowning it as one of the most-attended Pink Dot events in recent history.

The number of sponsors also snowballed from Pink Dot 2011, when Google was the solo corporate sponsor, to Pink Dot 2014, when Google was joined by other renowned international brand names—JPMorgan Chase, PARKROYAL on Pickering, CooperVision, Barclays, The Gunnery, BP, and Goldman Sach.

In 2015, Twitter, Cathay Organisation, and Bloomberg joined the band of merry corporate sponsors, followed by Apple, Microsoft, and Facebook in the following year.

2014 saw active opposition to Pink Dot from the Muslim community who spearheaded the grassroots movement, Wear White, led by Islamic religious leader Ustaz Noor Deros. Two years later, in 2016, the Christian community took over the campaign, led by Pastor Lawrence Khong, senior pastor of Faith Community Baptist Church.

In 2017, tightened regulations meant foreigners weren’t allowed to participate in the annual event. This was also the year when sponsorships from non-Singaporean corporations stopped, which led to a call for local support.

120 Singaporean companies stepped up, making Pink Dot 2017 the first to truly be for Singaporeans by Singaporeans.

Pink Dot 11 in 2019 took on a more political slant with the attendance of Lee Hsien Yang, brother of Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong. Lee came for the event with his wife, Lee Suet Fern, and his son Li Huanwu and his husband, Heng Yirui.

The Covid-19 pandemic saw Pink Dot morphing into an online event for the next two years, despite petitions put up by various groups who called for restrictions on Pink Dot’s live streaming. 27,000 people signed a petition asking the government to restrict the live-streaming to adult viewers.

Singapore’s Ministry of Social and Family Development acknowledged in its statement to the media that it was not the first time the Pink Dot event would be live-streamed. However, they stopped short of directly addressing the issue of the petitions.

The Dot

The peak expression and objective of Pink Dot happen when the dot is formed on the grounds of Hong Lim Park. It’s a sacred act that calls upon strangers, new-found friends, families, and Singaporeans across the gender and sexuality spectrum to take up metaphorical arms and demand equality.

With the burgeoning number of Pink Dot attendees year after year, the dot after which the event is named has since evolved to become a mass that takes the irregular shape of Speakers’ Corner—some say it looks like a dinosaur. Often, the crowd bursts and spills to the side as if to say even this physical space can’t contain the hopes and aspirations we hold dear.

And every year, Singaporean thespian Pam Oei would be tasked to round up participants for the winning shot. “Come in ah, come in! If you cannot see the pink heart, it means you won’t be in the shot ah!” she bellows as everyone obediently jostles for a spot to be counted.

“I felt quite proud and emotional,” Tan shared when I asked if she remembered how she felt when she first formed the dot in 2009. “And even now, thinking about it, every time I see the dot being formed, it makes me feel happy and proud that we have come this far.”

With a laugh, Fitri concurs. “To be honest, I enjoyed it, although it also felt a bit underwhelming, lah. Like, ‘Oh, we made a dot, and that’s it?’. I wouldn’t say we made a statement, but it felt like I did something real. Thinking back, I didn’t realise how impactful and memorable it would be now.”

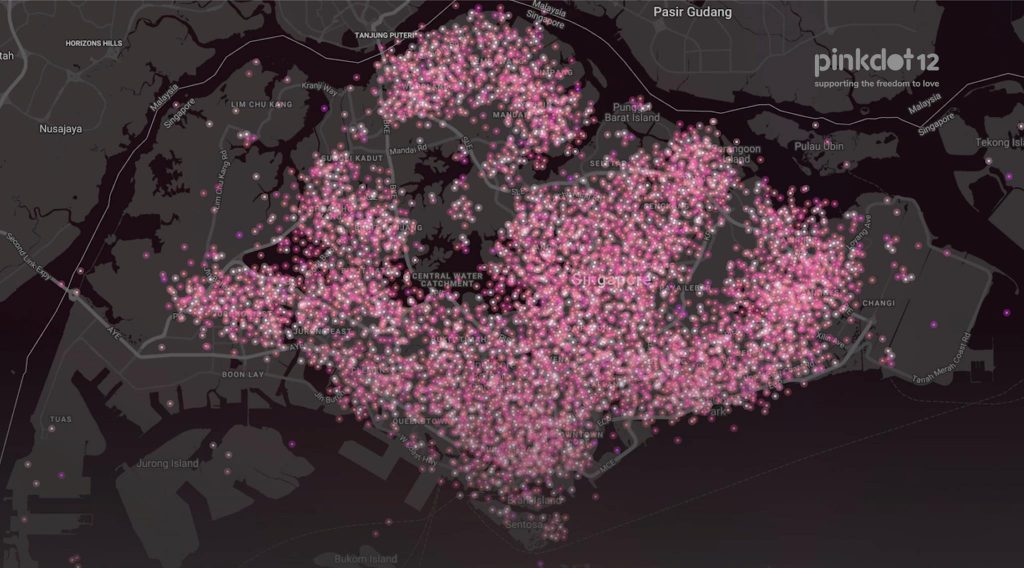

While impressive when formed in person, The Dot proved its malleability during Circuit Breaker and in the wake of a social-distancing reality. In 2020 and 2021, The Dot went digital, using geo-location technology so that participants can be counted from whichever nook and cranny of Singapore they reside. Nothing, it seems, can stop The Dot—not even a pandemic.

Pink Dot then vs now

The biggest setback to Pink Dot happened in 2017 when tightened regulations meant that only Singaporeans and Permanent Residents were allowed to attend the event.

2017 was also the year when former international sponsors like Google and Twitter were not allowed to lend monetary support to Pink Dot.

In his wrap-up speech on the Public Order (Amendment) Bill 2017, Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Law, Mr K Shanmugam, said: “My Ministry made it clear that we will not agree to foreign participation. As a Government, we do not take a position for or against Pink Dot. Still, we do take a position against foreign involvement in events like Pink Dot. That is not new, that has always been the law.”

The withdrawal of foreign sponsors and disallowing foreigners to attend Pink Dot was a sore talking point that Jess brought up when I asked what she felt was the difference between Pink Dot in 2009 versus now.

“On the brighter side, more families are attending now as well, with kids teaching and sharing with their parents and grandparents and vice versa.”

Tan thinks Pink Dot is a lot more polished and a lot more organised today—the scale is also completely different, she admits. “I do feel it’s become a lot more political, though I don’t think the organisers meant for it to become political. It’s other people who have made it political.”

“Isn’t that line of reasoning—that it is not political—difficult to justify when the Pink Dot organisers stand on stage demanding significant changes to the law?” I retorted.

“That depends, Zat. Is demanding equal treatment a function of politics or human rights?”

The future is optimistic… right?

Recent developments lead me to believe that the landscape of LGBTQ+ rights seems to be looking up with assurances given by Mr Shanmugam that the government is actively speaking with various groups on the viability of the repeal of 377A.

Still, Fitri worries that while the government may be forging forward with its efforts, society might move backwards.

“If you see what’s happening in the US, women’s rights are threatened. If even now, in 2022, countries like the US can move backwards, I worry that it will happen to Singapore also.”

Tan agrees. “I feel that abortion and gay rights will be under greater attack in the coming years in Singapore.” She likens it to a swinging pendulum: “We’ve gone this way, and now we’re going back the other way.”

People today, Tan went on to add, are less tolerant—they want to make everybody agree with them. “So it’s very polemical. It’s either left or right. Even in Singapore, the religious right has become more vocal.”

Jess is slightly more optimistic, believing that, in the words of a perennial gay icon, the late Whitney Houston, the children are our future.

“They are much more vocal and are fighting more intently for their rights. We might have paved the way and gotten the motion, but they’re the ones who would be the driving force to make a change if any.”

On legacy

“Do you think Pink Dot is still relevant today?” I ask Fitri as our dinner reaches its one-hour mark. “It’s sad that we still need it,” he replies with a sigh. “Having to think about Pink Dot and how it’s been around this long, I’m not entirely sure if we’re moving the needle.”

Legislatively, Fitri adds, Singapore hasn’t seen any changes ever since the first Pink Dot. It’s why he welcomes the slightly more political stance Pink Dot started taking in its tenth year.

“It should be that way. It has come to the point where we need to demand change and not have to play the “We are harmless, we’re just like you” card. That’s not our responsibility to educate them anymore.”

Tan is a little more hopeful in her perspective. She applauds that Pink Dot now has tents occupied by LGBTQ+ community groups who are there to reach out to younger members of the community, provide counselling services, or organise social activities.

“I mean, not every gay person wants to go to a bar, right? Pink Dot is great because it allows people to hang out in a non-bar environment.”

Our conversation brings to mind Tan’s memory of coming out when she was 17 and thinking she was a weirdo. “So to have Pink Dot, to celebrate your pride together, it will never be irrelevant. It will always be relevant to the times.”