All images by Stephanie Lee for Rice Media unless otherwise stated.

*Name has been changed

It is Sunday at Tanjong Katong. The air smells of rain and it rings with the bluster of cars surging through narrow roads. Coffee shops are aplenty in this colourful neighbourhood, where the remnants of Singapore’s colonial past remain ubiquitous.

In one such coffee shop, two transgender Muslims sit side-by-side.

As transgender Muslims in Singapore, they both traverse the complex intersection of religion and gender identity while existing at vastly different stages of their journeys.

This contrast would set the stage for the conversation I’m about to navigate with them both.

Trans Muslims Have Always Been Here

Singapore’s history is no stranger to trans people.

When Sir Stamford Raffles established Singapore as a trading hub in 1819, the Bugis people of Indonesia were one of the first communities to migrate to the burgeoning port city.

As part of their many distinct beliefs, the Bugis recognised five genders: makkunrai, oroané, bissu, calabai, and calalai. Calalai and calabai, respectively refer to transgender men and women.

In the context of Islam, trans people occupy a complex position in Islamic history both before and after the advent of colonialism.

Take the word mukhannathan, a term commonly used in Classical Arabic to refer to effeminate men who functioned in roles typically carried out by women.

While the term mukhannath are sometimes used to identify trans people, some Western scholars say that they were actually referred to as mukhannith.

But unlike the mukhannath, the mukhannith want to change their biological sex.

Some hadiths (sayings of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ) indicated that the Prophet cursed the mukhannathun and their female equivalents.

Other hadith accounts refute this, saying that he did not curse transgender people, but men who deliberately acted like women or vice versa. Malaysian Islamic scholar Wan Ji Wan Hussin noted in 2018 that the prophet did not hate trans people, and never stopped his wife from befriending a trans person.

According to Larry Nuttbrock’s book, Transgender Sex Work and Society, other early Islamic dominions like India’s Mughal Empire regaled their trans community with reverence and respect, affording them education and prestigious occupations alongside the nobility.

Fast forward to today. Singapore stands among a handful of Asian countries where transgender people are officially recognised.

Sex reassignment surgery has been legal since 1973, and those who undergo the procedure can change the gender marker on their identity cards.

Despite this, the trans community in Singapore continues to endure discrimination in a society that still primarily values traditional notions of gender—yet another relic of our colonial past.

Being Muslim and trans, then, adds extra challenges to the already precarious experience of being transgender in Singapore.

Two Trans Muslims, Two Different Stories

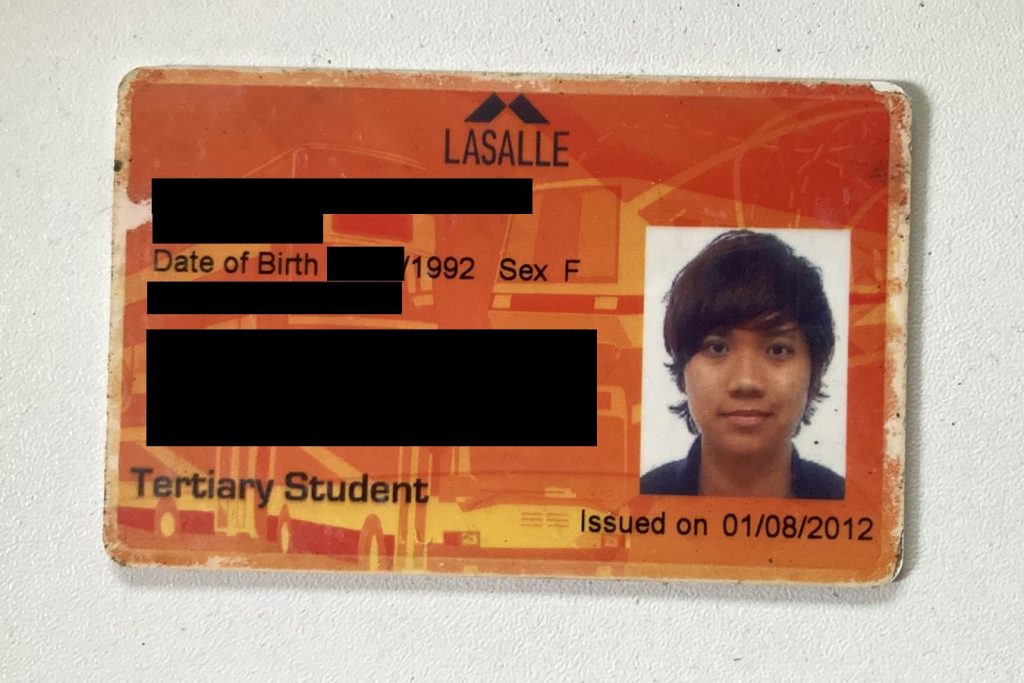

“My first introduction to the theory or concept of gender binary was when I was three,” says Ilyas, a 30-year-old bisexual, trans Muslim man.

“I took off my shirt because I saw my dad doing it. My mum yelled at me for it, though,” he chuckles. “She said only men could take their shirts off.”

Through such childhood experiences, Ilyas realised very early on that he did not align with the gender assigned to him at birth. It was a topic he could not broach with his staunch Muslim family, who are highly conservative on matters of gender and sexuality.

However, attending secular institutions like Tanjong Katong Girls’ School (“it was the Girls School Gayness”) and using the internet exposed him to diverse ideas of gender and sexuality.

He tousles his short dark hair periodically throughout this interview—it’s charming in a way. Every time he grins, the sharp turn of his stubbled jaw moves with him. Ilyas tells me his dead name and talks about his previous life as a young girl with nary a hesitation.

Ilyas began transitioning from female to male more than a decade ago. Today, his collared shirt is free of any unwelcome curves, a result of undergoing top surgery in 2020.

His body language is relaxed, and his eyes are luminous as if to say: This is who I am, but I honour who I used to be.

Sitting next to Ilyas is Jun*, a 20-year-old content creator. He is born female but identifies as a transgender man.

His solemn face is slumped beneath a snarl of short curls that he typically conceals underneath a tudung.

Unlike Ilyas, he rarely, if ever, smiles throughout our conversation. He does not even once mention his dead name. Still, similarities between the two abound. Like Ilyas, Jun grew up in a deeply religious and conservative family too.

As a student, Jun attended an all-girls madrasah (religious school) where the dialogue on trans people mirrored the conservative sentiments of his family.

When he began questioning his gender at the age of 13, the transphobic rhetoric encircling him from every angle prevented him from voicing his struggles.

Because of the intense loneliness and gender dysphoria Jun endured as a closeted trans Muslim man, he developed psychosis, suicidal thoughts, self-harm tendencies, and severe clinical depression. Jun continues to suffer from those symptoms today.

Navigating Gender and Religion

Still, it does little to tamp Jun’s faith. Like Ilyas, Jun’s identity as a Muslim is just as important as his identity as a trans man. The only difference is how that faith is practised, given their present gender presentation.

Like other Abrahamic religions, gender plays a central role in how faith is practised in Islam. Traditional interpretations emphasise strict roles explicitly prescribed to men and women.

For instance, Muslim men are forbidden from wearing silk or gold. Another example is the tudung (also known as the hijab), a headscarf worn only by Muslim women.

“I started wearing the tudung from the time I was born. I remember seeing a photo of myself as a baby, and I was already wearing it,” says Jun.

Jun continues to wear the tudung around his family but prefers not to wear it when he’s out without them.

“Although it does not make me feel dysphoric, I would rather not wear it because it symbolises femininity in Islam.”

On the other hand, Ilyas was around eight years old when he began wearing the tudung. This habit came about from attending madrasah classes every weekend, where it was part of the uniform.

He stopped wearing it when he was in his early teens. “It felt like it had a weight to it,” he explains.

“The hijab tends to be associated with women, and that made me feel very dysphoric.”

Gender also dictates how a Muslim should pray. For instance, women must pray behind men and cover their whole body except the hands and face. Men must lead the prayer at the front and cover their modesty only from navel to knee.

When he first transitioned and presented as a man, Ilyas was uncertain whether he should pray as a man or woman.

“I was like—okay, how do I resolve this?” he recounts. “But because I present myself as a male, I decided to pray as one.”

“It was important to me to be aligned to my gender as I prayed,” he explained. “I wanted to carry out this Islamic ruling as best as I could.”

While Ilyas chose to pray as his true gender, some trans Muslims pray in the manner of their assigned sex. Jun is one such Muslim—despite identifying as a man, he continues to pray as a woman.

“I contacted MUIS—the Islamic Religious Council of Singapore—about this, but they said I would have to pray as my assigned sex because I must ‘accept God’s design’,” says Jun.

We’ve reached out to MUIS for clarification, but they did not respond to our request in time for the publishing of this story.

The Process of Transitioning

Before transitioning, Ilyas opted to dress in a masculine fashion to balance his gender identity with the expectations of his religious mother, who believed in strict gender roles. “It was a decent compromise,” he explains.

It was only at the tail end of 2015 that Ilyas began socially transitioning. Social transitioning is when a trans person publicly affirms their gender identity. It can include changing their name, pronouns, dressing, and other external gender cues like voice and mannerisms.

He eventually began physically transitioning in 2016 and underwent top surgery (the removal of breast tissue) in 2021.

Ilyas’ reason for transitioning was simple.

“I was terrified of being buried as a woman,” he says.

In Islam, death rites, too, are gendered—the method of burial differs depending on the gender of the deceased.

Each corpse is typically wrapped in a plain white cloth (the kafan). If the deceased is a man, the common practice is to shroud him in three pieces of fabric that cover him from his neck to his feet.

If the deceased is a woman, she is typically shrouded in five pieces of cloth instead of three, covering her entire body, including her head and chest.

“I admit that Islam took a bit of a backseat while I was exploring my gender identity ,” Ilyas shares, admitting that his relationship with Islam, pre-transition, was tenuous.

“I thought that I would have crossed the line of no return by transitioning. People around me said there were limits to God’s love, and I had reached those limits by transitioning.”

In the end, transitioning improved his relationship with Islam.

“My relationship with my gender has actually strengthened my relationship with my faith,” he smiles.

“I could never really connect to prayers and everything because I felt like there was something incongruent with my identity.”

“But once I started transitioning, I began embracing my masculinity, which led me to develop strong ties with my religion. Now this feels right. Now when I worship, I do feel connected. I do feel grounded when I pray.”

Conflicted but Determined

While Ilyas was able to reconcile the idea of transitioning as a Muslim, Jun has not. His lack of familial support further compounds his hesitation toward transitioning.

“My family says Islam doesn’t support transgender people, and I’m a sinner. It’s making me doubt my faith because of the challenges I’m facing due to my gender identity,” he says, eyes downcast.

In navigating the complex and, at times, confusing intersectional throes of gender identity and faith, both Ilyas and Jun found strength and guidance in Singapore’s queer Muslim community.

Some examples of organisations directed toward supporting queer Muslims include Quasa—of which Ilyas is a committee member—and The Healing Circle.

Still, for Jun, interacting with Singapore’s queer Muslim community is a double-edged sword.

On the one hand, it has exposed him to different Islamic interpretations surrounding gender and has made him more open to living as a man.

On the other, facing many diverse interpretations of Islam adds to his uncertainty and confusion.

“There is still a part of me that believes transitioning and living as a man will not be punished. Right now, I am conflicted and need more advice from people more knowledgeable on this topic,” he says.

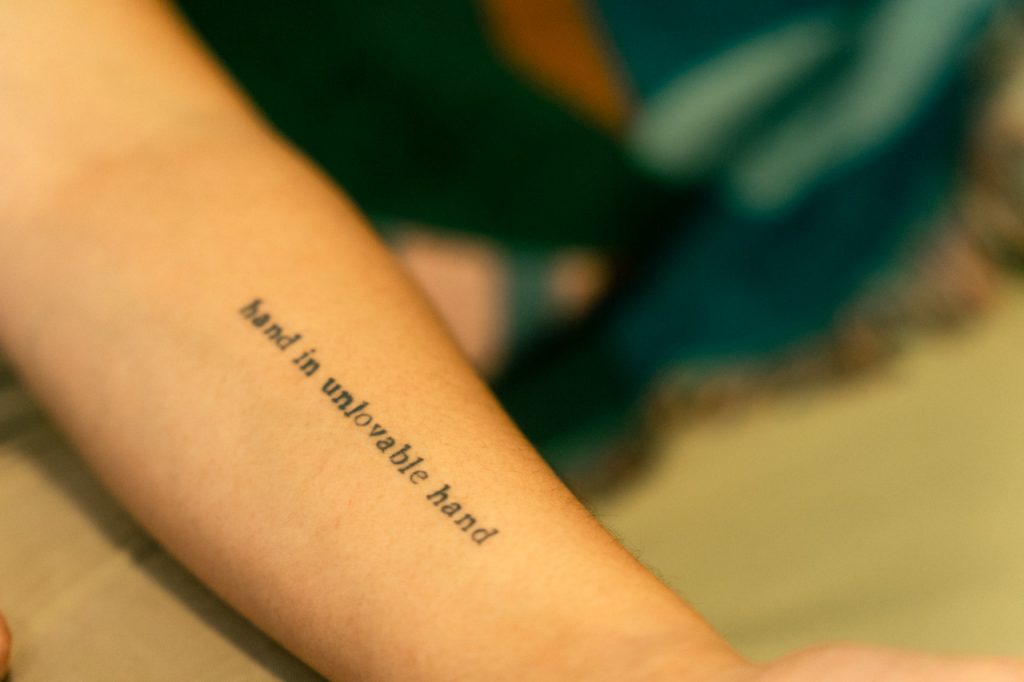

While Jun is reluctant to transition fully, he tries to live as his true gender in more subtle and socially-acceptable ways.

He takes voice masculinisation lessons, cuts his hair short, wears “masculine” clothes, and puts on chest binders.

“I started taking these steps because the person I wanted to be was not the person reflected in the mirror,” he explains.

Doing all these, he tells me, decreases his sense of gender dysphoria while balancing the expectations of his community and religion.

‘I could feel the other men judging‘

Today, the relationship between Singapore’s Muslim and trans communities remains fraught with tension.

To comprehend this, we only have to look back at Samsung’s 2022 ad featuring a drag queen and Muslim mother. The video triggered an avalanche of criticism from many Muslims in Singapore, who rallied against the depiction of a Muslim person defying gender norms. In the end, it was pulled by Samsung.

This hostility is not lost on some Singaporean transgender Muslims. This can be seen, for instance, in the way that Ilyas does not feel safe at the masjid (mosque).

“The last time I went to the masjid was in 2019. At the time, I still hadn’t undergone top surgery, so I went to pray in the men’s section. I could feel the other men judging and staring at me,” says Ilyas.

Ilyas’ relationship with his mother is also fraught with tension.

“My mother is not accepting at all. I mean, she didn’t throw me out, but I eventually moved out myself. My dad isn’t in the picture,” he explains.

“Luckily, my siblings have been so, so supportive throughout this whole journey. Two of my siblings are different shades of queer, so they understood me.”

In an Instagram post about his experience during Hari Raya as a trans Muslim man, Ilyas writes:

It’s hard, every Raya, for me to step out the door and brace myself for the violence I will inevitably face when I meet my family and relatives. The constant misgendering and deadnaming the passive aggression, having to pray behind closed doors because the idea of me worshipping as a man is unthinkable… Every Raya is bittersweet—there is the quiet joy of family and yet the constant reminder that people like me are not welcome, that the idea of us practising our faith is preposterous.

He continues on a bittersweet note:

The silver lining one year was my aunt coming home from England and asking me if she could still hug me, acknowledging the distance one should keep when interacting with the opposite sex. She asked me about my new name and asked me if I had [a partner]. And this was such a pleasant surprise, it caught me off guard. Perhaps in time, she won’t be the only one.

Jun too had unpleasant experiences with family. During Hari Raya in 2021, he came out as transgender to his family. In response, they accused him of being disrespectful to Allah.

Jun’s unaccepting family plays a prominent role in his troubled relationship with his gender identity. “I think I would only transition if I had support from my family,” he says sadly.

Islam places ties of kinship in high regard, and many Muslims are taught never to sever a relationship with their family from a young age.

This makes it all the more painful when trans Muslims are rejected by their loved ones.

Can Two Vastly Conflicting Identities Co-Exist?

Despite the challenges, Ilyas continues to be steadfast in his faith.

“I honestly truly believe that this is the truth of the universe. No matter what, I am a Muslim,” he says.

“My faith and gender are intrinsically tied together,” he continues. “It’s not one or the other… these things can co-exist.”

“Religion did take a bit of a backseat as I tried to navigate my gender. I was stuck in this position where I felt like a sinner and couldn’t be redeemed. But the thing is… I’m never not going to be a Muslim. It’s how I was born and how I’m going to die.”

As for Jun, he remains undecided about his future as a transgender man. Due to his conflicts with religion, family, and community, he has temporarily halted plans of transitioning.

Nevertheless, he remains steadfast in his faith despite his challenges.

“I love God. I am thankful for all They have given me,” he says. “If God created us as perfect beings, then I should be able to accept that being trans and Muslim is just my version of perfection”.