Top image: Marisse Caine / RICE File Photo

The Singapore Kenneth Michael Bong remembers from his childhood was a multi-lingual melting pot.

The corners of the 70-year-old retiree’s eyes crinkle as he recalls frequenting a chapati shop somewhere in Little India in the ‘70s. It was staffed by a Punjabi woman and a Tamil woman who’d frequently holler at each other in Malay over the bustle of the store.

ADVERTISEMENT

His paternal grandmother was Peranakan and would speak Malay to him. His Eurasian maternal grandparents also spoke Kristang, a creole language spoken by those of mixed Malay and Portuguese descent.

Kenneth grew up amongst such a rich tapestry of languages that he would sometimes mix them up. Only later in life did he realise that certain words in his family’s vernacular like ‘buziu’ (monkey) and ‘kambra’ (room) were actually Kristang.

“I thought it was English!” he chuckles. “We’d scold our kids ‘buziu’ all the time without even knowing where it came from.”

A few decades later, things have changed markedly here. The lingua franca now is English. And with our growing English proficiency also comes the dilution of our mother tongues and dialects. Being a banana or ‘jiak kentang’ is socially acceptable—boastworthy, even.

A 2020 Institute of Policy Studies survey revealed that a growing number of Singaporeans identify the most with English. This group (over a third of Singaporeans) has grown at the expense of other groups, which identify more with the mother tongue languages of Mandarin, Malay and Tamil.

It’s a troubling enough trend for Minister of Education Chan Chun Sing to address at the 2023 Mother Tongue Languages Symposium.

“This is a major concern for all of us. If we do not do anything, we will start to lose our bilingualism edge,” he warned.

There’s an irony here, given that it was the People Action Party’s bilingualism policies, introduced after they took power in 1959, that established English as the lingua franca and marginalised dialects. Other languages outside of the Big Three official mother tongues—Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil—naturally fell by the wayside.

Yet, there’s growing defiance. Some Singaporeans are going against the grain, making deliberate efforts to reconnect with the buried languages of their forefathers.

But this isn’t just a story about language; it’s about reclaiming one’s identity at a time when so many seem to be eager to leave culture and traditions behind.

Your Mother’s Tongue

At first, the term ‘mother tongue’ sounds self-explanatory. It’s your mother’s tongue, ergo the language your mother—or your family—speaks.

The reality, however, is a little more complicated. My parents speak English, Malay, Hokkien, Cantonese, and a smattering of Mandarin. Meanwhile, my siblings and I are bona fide bananas (I’ve been told by a colleague that my Mandarin is “weird”).

Languages aren’t inherited; they’re shaped by our social environment. Often, the languages we connect with aren’t the ones we’re most fluent in—or the ones taught in school.

As a current JC student, Peh Zhi Ning’s immediate association with the term ‘mother tongue’ is naturally the school subject. But when I probe deeper, Zhi Ning admits that even though she learned Mandarin in school, it doesn’t really feel like her mother tongue.

That’s why the 17-year-old, who’s Hokkien by blood, is trying to learn the dialect. The Raffles Institution student has been a member of Raffles Dialects, a student interest group, for about a year.

Her Hokkien-speaking grandmother raised Zhi Ning till around 12, so the dialect is familiar to her ears. But she was never properly taught the dialect by her English-speaking parents and struggled to string a sentence in Hokkien together.

ADVERTISEMENT

“Even though I’m more fluent in Chinese naturally than in Hokkien, I feel that it’s something that connects you to your past,” says Zhi Ning.

Funnily enough, the fellow student who’s been helping Zhi Ning improve her mother tongue isn’t even Hokkien—he’s Teochew.

Gareth Quek, who co-founded Raffles Dialects, says you can tell a lot about someone from how they speak dialects.

Apparently, Zhi Ning’s Hokkien pronunciation indicates that her ancestors originated from Quanzhou in southern Fujian. For example, she says “zer” instead of “zei” (another common variation) for the word ‘sit’.

The 18-year-old agrees with Zhi Ning that mother tongue languages offer something English doesn’t: “I speak English a lot, and culturally, I’m very Westernised. But it’s also good to have your mother tongue as a cultural anchor so you can express yourself and understand your family heritage.”

He’s right. We’re a product of everything that has come before us, and keeping our family’s language alive is one way to honour that. English is comfortable and easy. And we should speak it, especially when we’re in diverse spaces with different ethnicities.

But it’s not the language our forefathers spoke when they built this country.

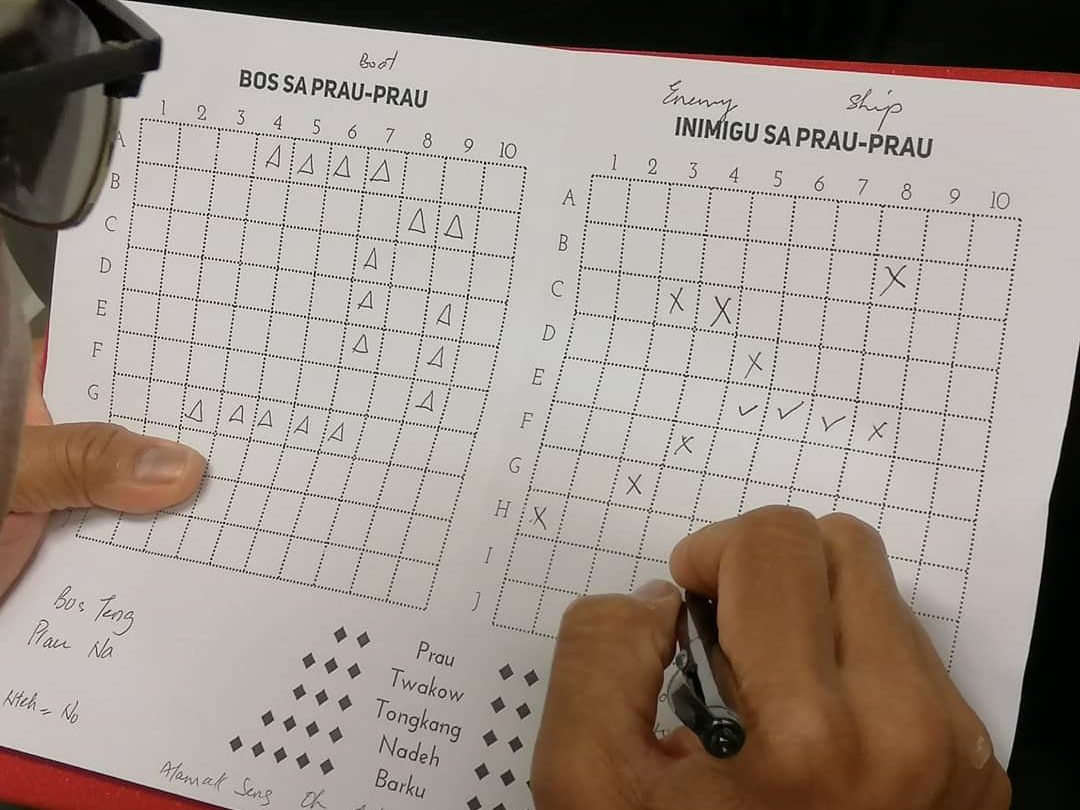

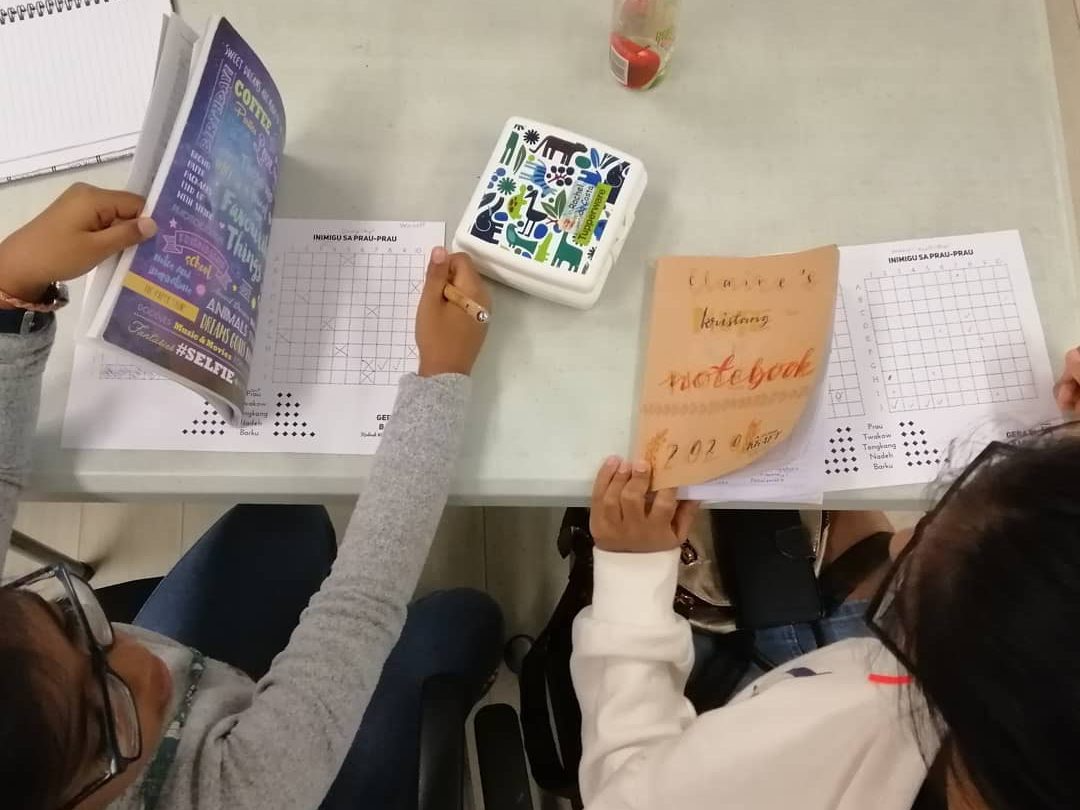

For Kenneth, reconnecting with his cultural heritage is a big reason why he enrolled in Kristang lessons held by Kodrah Kristang four years ago. The other reason, he says, is to keep his brain active.

Spearheaded by Kevin Martens Wong, the Kodrah Kristang project aims to revitalise the critically endangered creole language used by some Eurasian folks. There are less than a hundred native Kristang speakers left in Singapore, some Eurasians estimate.

Over the years, English has become the first language of most Eurasians. When it comes to picking a mother tongue language to study in school, though, they have to pick from Chinese, Malay, or Tamil.

Kenneth says he slowly lost touch with Kristang as he focused more on Malay, which he learned in school in the ‘60s. He also admits that he doesn’t have a natural inclination towards languages.

Still, he’s firmly convinced that we should be trying to preserve our multi-lingual culture. He explains that he sees the dilution of our languages as a dilution of our heritage as well.

He likens us to trees: “If you are strong in your own roots, you can adapt and sway in the wind.”

As the world gets more fractured and uncertain, strong roots will help us weather storms.

The Joys of Relearning Your Mother Tongue

For some, relearning their mother tongue is a matter of practicality.

Sharlyn Seet, a 22-year-old content creator, cooly admits that she never prioritised Mandarin in school because of the low ROI compared to other exam subjects that she could cram.

“There’s no defined scope, you know? Chinese is something that you have to keep learning. You can’t just memorise it in a night or a day,” she says.

“I learned Mandarin in school, and I only spoke it in school, more specifically, only twice a year during my oral exam where we had to speak.”

Like many other English speakers, Sharlyn shelved her Mandarin once she’d completed all her national examinations. She admits she didn’t feel a pressing need to learn Mandarin until several recent trips to Mainland China and Taiwan.

Those trips drove home how abysmal her command of the language was. She had trouble communicating with stall owners and “felt like a child” when she was asking for directions.

“I always used to joke saying, ‘Oh, my Chinese sucks.’ Well, eventually, I was like, yeah, my Chinese sucks, and I have to do something about it to make it not suck.”

When she returned from her travels, she bought herself a Mandarin children’s book and was humbled by how much she didn’t know. Vocabulary like ‘zhi sheng ji’ (helicopter) sounded utterly new to her.

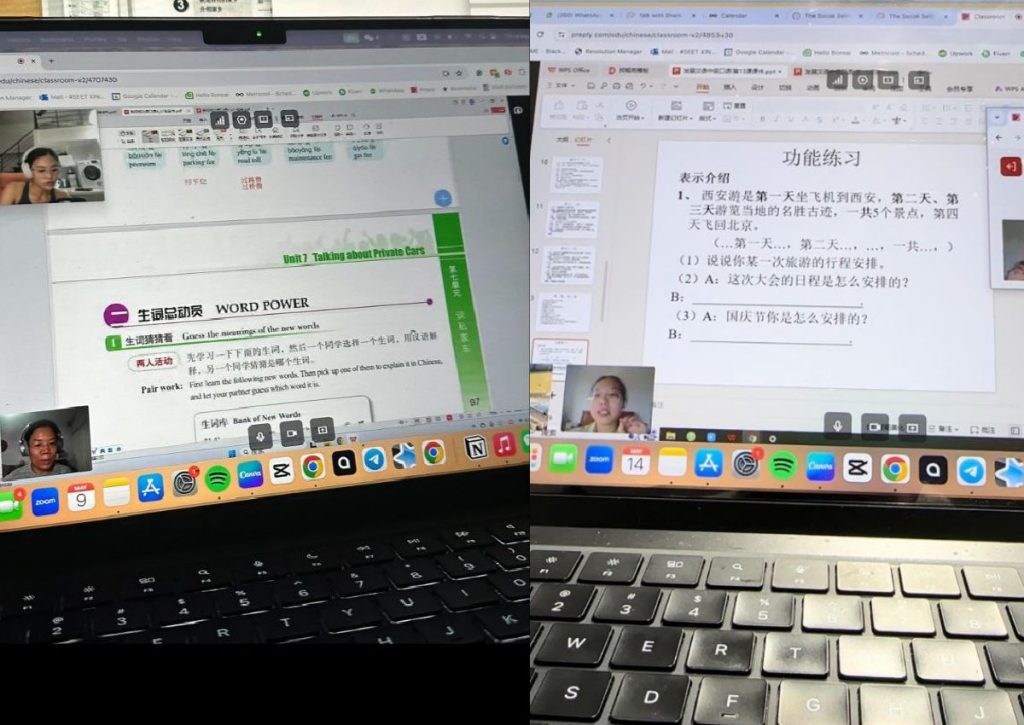

After memorising the book, she moved on to flashcard apps and online lessons taught by native speakers. Having to speak Mandarin to native speakers was one of her biggest fears, but she knew she had to force herself to overcome it.

Today, she’s much more comfortable speaking the language, and has seen marked progress in her vocabulary. She’s even able to rattle off some of the words she’s learnt in an impeccable Standard Chinese accent.

She adds that one unexpected result of her Mandarin learning journey is that she’s since gained a new appreciation for her Chinese heritage.

“My younger self would not believe what I’m saying now, but it’s such a precise and beautiful language with so much history that one can never, ever finish learning about.”

Her improvement has even inspired her friends to consider learning Mandarin—the same friends who’d joke along with her about their poor Mandarin.

Now, as an adult learner, she’s willing to fork out about $200 each month for lessons. What changed for her from her schooling days till now was her interest in the language, she says. She’s now realised that it isn’t something that can be forced.

For people like Zhi Ning, Gareth, and Kenneth, learning their mother tongue isn’t very practical since Hokkien and Kristang aren’t as widely spoken in Singapore. But there are other perks.

“I find the appeal of Hokkien for me is the fact that—okay, it sounds a bit stupid—but as a young person speaking it, you get aura,” Gareth offers.

Zhi Ning’s amused, but she doesn’t disagree.

One recent win for her, she tells me, was watching Wonderland, the new tear-jerker starring Mark Lee and Xenia Tan. She could understand most of the Hokkien dialogue without looking at the subtitles. The movie was also a special moment for another reason.

“Most of the time when I see that Hokkien represented on TV, it’ll be those old shows like the one that goes ‘wa meng tee’ [Editor’s note: she means the Taiwanese family drama Love]. Seeing new media coming out that represents Hokkien is quite interesting.”

Zhi Ning and Gareth also say it’s become a secret lingo they use when they don’t want their peers around them to know what they’re saying.

As for Kenneth, he found community among his fellow Eurasians trying to reclaim their language and identity. There are even some non-Kristang folks who’ve joined Kodrah Kristang to learn more about the culture.

“So many people have come out of the woodwork [to learn Kristang]. I never thought there were so many other people who were interested to learn it.”

Kenneth is self-deprecating when he tells me that there are many more people in the group who are more proficient Kristang speakers than he is. But having people to speak the language with has helped him tremendously. He flashes a grin as he tells me that he hopes to be fluent one day.

Language & Identity

People like Sharlyn, Kenneth, Zhi Ning, and Gareth are outliers. They’re still outnumbered by the bananas and ‘jiak kentang’ people out there.

It’s understandable. Learning a language takes serious time and effort. And as Sharlyn has realised, people can’t be compelled. They’ve got to be genuinely interested.

Gareth says trying to promote dialects sometimes feels like “a losing battle”. He points to Raffles Dialects’ low numbers—it currently has 15 members, and only a handful of students have joined each year.

Zhi Ning sighs.

“You need to be good in English to excel in studies, and then to enter the job field and to get a good job, as prescribed by your parents. So I think it’s understandable that we are kind of losing touch with our mother tongues and with our dialects because it’s so socially acceptable to only be good at English.”

It begs the question: with how much our language preferences have changed, should we consider redefining what constitutes a mother tongue?

Linguists like Nanyang Technological University’s Tan Ying-Ying have suggested that the English language can be considered a mother tongue because of how much it penetrates Singaporean life.

We speak it with our parents; we’re proficient in it; we identify with it. And when we’re free to choose which language to use, we often default to it.

In fact, the associate professor argues in her 2014 paper that granting English mother tongue status could aid language policymaking.

“This move will not change the way of life in Singapore, and the bilingual education system that Singapore is so very proud of will remain as it is,” she writes.

“In fact, the bilingual education system will be a lot more flexible with English as a mother tongue because there is no longer any need for anyone to be tied to one’s ethnic mother tongue.”

Though it might make sense linguistically, it’s still strange to think of English as our mother tongue.

For decades, English has been the lingua franca. And our mother tongue (at least in school) has been prescribed by our ethnicity.

Back when founding father Lee Kuan Yew first introduced bilingual education, his rationale was that English should be the working language as it would enable different ethnic groups to communicate and bond with each other. The mother tongue language would ensure that each ethnic group was still connected to its cultural heritage and values.

Singapore’s brand of bilingualism is not just about being able to speak two languages. Instead, it’s about unity in diversity—being able to communicate with our neighbours while retaining our roots.

Which is why the slow erosion in mother tongue proficiency is concerning. Is it a sign that we’re forgetting our roots? Can we still preserve our Asian and Singaporean values amid growing exposure to Western lifestyles and ideologies in the media we consume?

Keeping a Language Alive

“They usually give me discounts. Sometimes, I get free food.”

Gareth is telling me about the perks of speaking Teochew to his school canteen stallholders. It’s a fun anecdote, but it quickly takes a poignant turn.

“There was a very interesting case where the auntie thought I was from China because she was like, ‘No one speaks Teochew in Singapore. Why do you speak Teochew?’”

To be fair, it’s a valid assumption—dialect use in Singapore has indeed been dwindling, especially among youths. It’s gotten to the point where experts say it’s at risk of fading away eventually.

In our 59 years as an independent nation, we’ve gone from multi-lingual to bilingual. Now, it seems like some of us are effectively monolingual after leaving the education system. Beyond the official mother tongues we learn in school, we’re also hearing less of the vibrant tongues that connect us to our ancestors, like Hokkien, Malayalam, or Slitar.

It can be sad to think about languages dying out. Losing these languages means losing a whole chunk of our history.

But the bright side is that languages don’t die easy. Rare as they are, it’s people like Sharlyn, Zhi Ning, Gareth, and Kenneth that serve as guardians of sorts.

We all ache for a sense of belonging. We want to feel like we’re a part of something bigger than ourselves. We want to know who came before us. We spit in test tubes and send it off to a lab somewhere, hoping to uncover the stories of our ancestors in our DNA (all that just for them to tell us we’re “broadly Southeast Asian”).

Yet, relearning the language of our mothers goes beyond cultural preservation. It’s about reclaiming our identities as citizens of a relatively young nation with scarce legacies.

Perhaps being truly Singaporean means taking pride in the unique elements that shape our personal identities—including the languages that bridge us to our past and define our future.