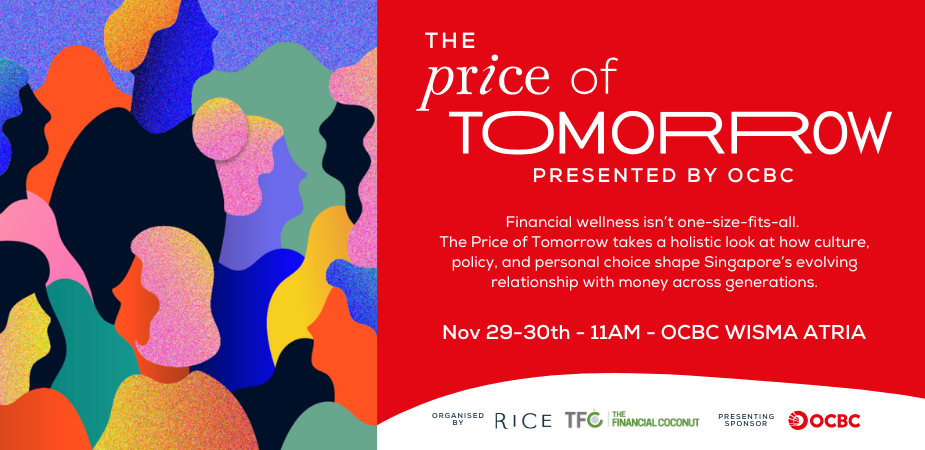

The Price of Tomorrow presented by OCBC is a financial wellness festival held in conjunction with The Financial Coconut and RICE Media to take a holistic, human look at the role of money in our lives.

All images by Darren Satria for RICE Media.

Could millennials be Singapore’s last sandwich generation?

Back in the day, popping out a kid or two as ‘retirement insurance’ used to be common. These days, however, millennials are bucking traditional expectations, choosing the Financial Independence, Retire Early (FIRE) lifestyle, Double Income No Kids (DINK) lifestyle, or both.

In other words, we’re relying on ourselves instead of our non-existent kids to fund our golden years.

There are some encouraging statistics. A 2019 survey by digital wealth platform Syfe found that millennials in Singapore were more prepared for retirement than their middle-aged counterparts. And in Etiqa Insurance Singapore’s Retirement Insights Report 2024, 75 percent of millennials and 69 percent of Gen Z respondents said they were confident of achieving their retirement goals.

As a millennial who’s been working and saving for the better part of seven years, I’d consider myself part of the aforementioned 75 percent. But at a recent live podcast event as part of The Price of Tomorrow presented by OCBC, which The Financial Coconut hosted in conjunction with RICE, I found myself tempering my hubris. Just slightly.

The panel, which brought together caregivers, financial planners, and hospice professionals, examined the financial pressures of caring for their ageing parents, their own future selves, and, for some, their children too.

We grow up hearing that we should be saving for a rainy day. But how many of us really have an inkling of how much we need for this figurative stormy period in life? And what else do we need to rethink when we step into the position of caring for our ageing parents?

Time Is Money, Health Is Wealth

Even before any health-related calamity strikes, Singapore’s rising life expectancy (from 78 years in 2000 to 83.5 in 2024) means that millennials will have to support their parents, and eventually themselves, for longer than any generation before them.

When health issues do inevitably take root, it’s often hard to estimate just how much you’re going to need to spend.

Panellist Timothy Liew, Head of Investments at OCBC, offered the story of his grandmother’s stroke as a cautionary tale.

“My grandmother back then was 88 years old. My parents thought maybe she had six or seven months to live [after the stroke] and they planned their whole schedule just to tide this thing over,” he said.

“She lived another four years.”

Having a living grandparent is better than grieving their passing, of course. But the costs of prolonged care do add up quickly: Medical supplies, home renovations, transportation, and the loss of income from a family member who stops working to provide care.

And as medical costs continue to rise—tune in to Reggie Koh’s The Financial Coconut podcast for a fuller picture—even the most disciplined savers might find the burden too much to bear.

“You can’t really run an investment strategy that outpaces medical inflation,” Reggie added.

When Policy Collides With Reality

Even when families plan carefully, Singapore’s welfare architecture can make caregiving feel like a bureaucratic obstacle course.

Veteran journalist and caregiver Bertha Henson described it bluntly.

“First, there’s the national means testing, and then after that is the household means testing. The household means testing is different for health and different for education. It can be household income gross or household income per capita. So basically, we’re in this whole big matrix of numbers.”

Today, Bertha has two domestic helpers to help her care for her bedridden mother, a decision that, to outsiders, might signal privilege. But in reality, it was a logistical necessity.

“It’s not that I’m very rich,” she said.

“When my mother fell, she was so incapacitated that one helper and I couldn’t cope. They didn’t allow her to be discharged from the hospital until I made arrangements [to hire a second helper].”

Others on the panel described how policy logic can ‘penalise’ caregivers. Dr Chong Poh Heng, medical director of HCA Hospice Care, recalled moving his parents from their HDB flat into his own home.

“When I took Mum and Dad from their flat to live with me, I lost everything,” he said. The household income suddenly spiked on paper, disqualifying his parents from subsidies they previously received when they were living by themselves.

“Your elderly person is best living alone,” Bertha quipped. “Don’t kaypoh and try to be a hero. Once you’re part of the household, your means testing will ‘burst’ and your poor elderly person will have no benefits.”

Bertha also admitted she only discovered the existence of the Home Caregiving Grant while conducting research for her book, When Mama Fell. She could have been collecting up to $400 a month to help defray the costs of caring for her mother, but had missed out simply because she wasn’t aware of the grant.

“When you’re younger, you think you’re internet-savvy, that you can find anything,” she said. “But what you really need is something tailored to your situation, not general advice.”

For some, financial stress isn’t only about scarcity. It’s also about control. James Leong, host of the podcast This Is What Caregiving Stress Feels Like, pointed out that money can become “a weapon” within families, used to dictate decisions, form alliances, or exert pressure.

“As much as money is a resource, it can also lead to unhealthy dynamics and cause even more stress.”

In caregiving, it’s often hard to estimate just how much time and effort you truly need until you’re in the thick of it. Unfortunately, Singapore’s caregiving safety nets seem to be built on tidy assumptions: that needs can be quantified based on the housing you live in, that families will absorb the strain, that people know where to find help.

Breaking the Cycle

If caregiving is so unpredictable for our bank accounts, what are we to do? How do we prepare for something that’s so fluid?

Timothy’s rule of thumb is deceptively simple: invest at least 10 percent of your take-home pay. “That’s how you ensure your kids won’t become the sandwich generation,” he said. “That’s how you take care of yourself.”

For the DINKs who may choose not to have children, the responsibility is different but no less urgent. Without children to rely on, they must plan early to avoid becoming a burden to relatives or the system.

The conversation about care in Singapore is often centred around filial piety and duty. But perhaps a real measure of progress will be the burdens we millennials shoulder instead of passing on as we age.

The Price of Tomorrow presented by OCBC is a financial wellness festival held in conjunction with The Financial Coconut and RICE Media to take a holistic, human look at the role of money in our lives.

Sign up for the next live podcast, Financial Socialisation: Trauma, Education and Accumulation for Your Child, taking place on Nov 13.