I can do it all.

This is the mantra we rehash repeatedly, adamantly believing that our inability to complete our tasks is simply a result of poor time management or unfocused attention. If only we could reshuffle the items on our plate, we tell ourselves, we would surely be able to squeeze it all in. We are aghast to think that the solution is potentially to take some things off the plate rather than carry out a simple exercise in rearrangement.

This drive for productivity is not an individual problem, but a collective one, espoused by two Southeast Asian short films in this year’s Singapore International Film Festival line up. More is not necessarily better has been emphasised before, but even getting to less is more takes work. New kinds of innovation require gruelling effort to pioneer, while sleepless nights usually precede breakthrough. Yet, we fail to understand that this incessant march toward progress comes at a heavy cost that we cannot possibly afford, a new kind of expensive we have yet to comprehend. From mental exhaustion to environmental ravage, these films expose the consequences of an accelerated lifestyle, one that has neither put on the brakes nor shown any intention of doing so.

Burnout has been the constant companion of our generation. When leaving work on the dot becomes a privilege and leisure time feels foreign and undeserved, a recipe for disaster is surely brewing. In People on Sunday, Thai filmmaker Tulapopo Saenjaroen tackles this issue head on with a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the contemporary obsession with work. Mirroring scenes from a 1930s German film with the same title and employing reflexive tactics to audacious effect, Saenjaroen exposes the ludicrous ways in which we constantly succumb to the yoke of labour.

SGIFF X RICE conducted an interview with filmmaker Tulapop Saenjaroen.

It is very difficult to pin down the exact first point of interest. On one hand, I feel like it has come from myself being tired all the time, creating some kind of cobwebs in a vacuum. On the other hand, I would say it’s something that has been developing from my written works years back. At that time, I was interested in free time in the neoliberal age; not to question whether it exists or not, but rather studying its implementation and to question its representability, and how much does ‘free’ cost.

In the process of piecing the film together, how much was scripted and how much was free flow experimentation?

Most of the scenes were scripted. However, it wasn’t like a detailed script; it’s more like lists of images I wanted to have in the film and more of framing conceptual ideas how the scene will play out. For example, the scene where four performers are having a limited words conversation, they were asked to improvise within conditions that were pre-set.

The free flow shooting will be more on the part where the behind the scenes and the compilation of found and shot footage take place. But again, the ideas of what kind of images I wanted were listed beforehand.

While an expose on the discourse of work, it is ironic that this film is ultimately still a product of work. How do you respond to that irony? Do you think that our preoccupation with work is inescapable?

I’d been feeling like I became the characters in the film more and more while I was editing… Well, the decision of making the film as a product of work is conscious from the very beginning in the writing process; for me, it is not, like, all or nothing—not to eradicate all work—but it’s more of a question of not only how we work but also how work works upon us, what does it mean to be worked upon; is it a signed contract? A threateningly forced signed contract? An unconsciously signed? Or no contract at all? For me, the paradoxical aspect of the film is essential in order to reflect these questions.

How did you approach the character of the cameraman capturing the behind the scenes moments? What were you trying to achieve through his more introspective narration?

For the second part of the film, I wanted the character to contrast with the first narrator; to propose another aspect towards work in the same situation. To be more specific, I wanted to step out from the actual aestheticised production, to another layer of production/performance. For the character’s confession, I wanted to emphasise more on his works, through his mind and emotions. For me, it is a process of peeling off the surface to encounter another surface.

I would say no one is naively on for the ride, including the editor character. I think they all have different interpretations/purposes on what we’re doing, and I guess, no one has any absolute answer to anything at the time of production. During the production, I still asked myself and others, half-jokingly, “What is this film about?”. In fact, a lot of people in the team are also filmmakers and freelancers, so these kinds of stories are not too far from their daily lives. So even though everything is fragmented, I guess we still share some common ground.

How do you regard the function of the frame/camera? It seems that people automatically “perform” for the camera. Can the frame truly capture what is authentic?

I think that the frame can never capture what is in the frame only; things within it and the way it’s framed always refer to or are associated with things outside the frame, even if they’re not visible. So “perform[ing]” in front of the camera could tell a lot of stories reflecting in various dimensions in its own way too.

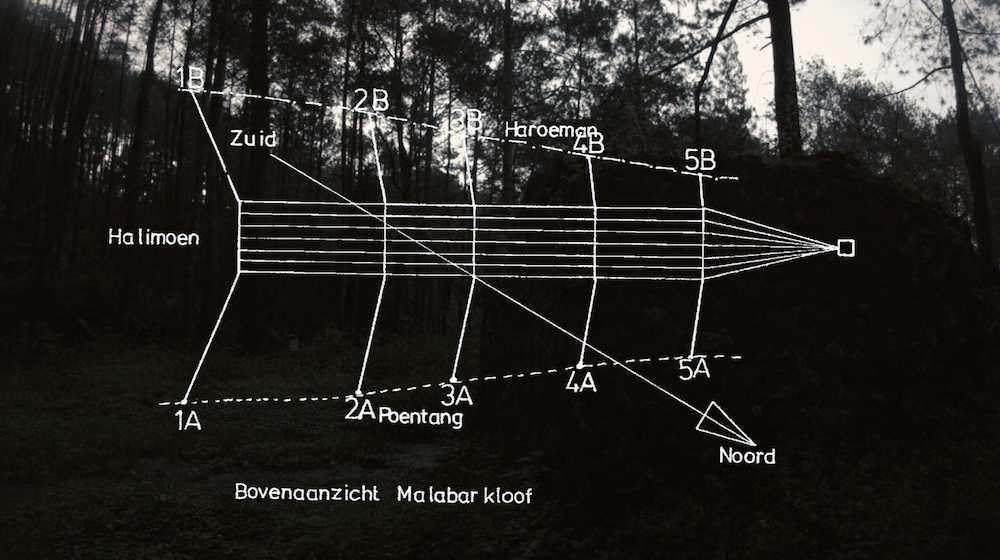

Opening with a cryptic number, we are taken on a trek through overgrown foliage belying weathered stone pillars, the gargle of jungle ambient pulsing through the screen. Foggy landscapes create an otherworldly atmosphere, resembling something out of a Jurassic Park escapade. Peeling back the fossilised layers from Southeast Asia’s first radiotelegraphy station, Radio Malabar, Indonesian artist-filmmaker Riar Rizaldi makes his experimental foray into the lesser known histories of the archipelago’s colonial past, uncovering buried narratives of colonial imprint, indigenous mythologies and human interference on the ecology.

SGIFF X RICE conducted an interview with filmmaker Riar Rizaldi.

I’ve always known of the place Radio Malabar, as it was near my mother’s home, but I never knew the rich history behind it. So it was only after discovering the stories behind it that I decided to make a film about it. In terms of research, it was not that difficult as the local history archive was full of stories, and I also managed to use resources from a website set up by fans and collectors of radio history in Europe. The indigenous mythology was also accessible to me through local history lovers, so there was quite a lot of material to work with actually.

How did you go about scripting your film? Which parts were planned and which parts did you allow for the film to develop organically?

Actually most of it was improvisation in the field, I worked with my partner and it was just two of us shooting in the area. What helped was that we made frequent trips to the area so we became familiar with the topology and where we could place the camera to capture different angles. On one of our outings there we also chanced upon the workers trying to clear the grass and so we captured the process organically as well. For the edit, yes, it was largely experimentation, but I also did have a pattern in my mind since I was able to accumulate all the different materials ranging from archival footage to what we shot. As the edit progressed, the script would change, and I’d go back to the edit again and so on. I think I spent the most time in the edit, in fact more time there than shooting.

I don’t come strictly from a film background, but rather from that of a media artist. So naturally my interest was in using a variety of visual communications to convey the experience, in hopes that it would be more engaging and also thought provoking. So I suppose it boils down to the roots of my practice where I frequently play with presentation.

In terms of the mystery part, I really like blurring the line between fact and fiction, and I’m especially interested in the idea of myths, something fabricated but also treated as true. So in Tellurian Drama there is a lot of myth making going on, even the narrator will cause you to question what, or who, is real or made up? So I think that’s something really fun.

Yes, originally, this piece was supposed to be staged in a white cube space, but due to COVID it was cancelled and this project was in limbo, so I decided to submit it to film festivals. The main difference for me between white cube and black box is the presence of time. In a white cube space, the audience is free to enter at whichever part of the film they first encounter and free to leave it anytime they want, but in the black box, there is almost an unspoken rule that you have to follow the images from beginning to end. You also mentioned the heavy use of text, which I agree with. In the white cube space, there is the addition of different mediums and materials to supplement the moving image, so definitely the interaction with the piece in the white cube will be quite different from that of the black box. But at the end of the day, I think it is not so important that audiences must understand all the historical facts or philosophies conveyed. I’m quite happy for them to take away whatever they manage to absorb.

Sound design also plays a crucial element in your film. Could you share your thought process while creating the aural soundscape for your film?

Yes, actually when I first visited Radio Malabar, I was struck by the soundscape of the place. The location is actually close to the city yet it’s up in the mountains, so I encountered a soundscape I never knew before. It felt like it was surround sound. When piecing together the film, sound was actually one of the first things that entered my head. I wondered to myself what the sounds of the old Radio Malabar would have been like, and I knew I wanted to present the current soundscape of Radio Malabar as it is. At the same time, I also engaged a composer to create these synthesized, wave-like types of compositions since the entire theme was on this radio station. He listened to all my field recordings of the place and began to design the sound piece. So the aural soundscapes you refer to are really a dialogue of how to present the original sounds of the place in a more abstract and immersive form.

What draws you to the intersection of technology, environment and humankind?

I think I’ve always been fascinated with technology as a kid, and I grew up watching a lot of science-fiction cinema, so this was a natural occurrence when I started my practice as an artist. I try to present ideas of technology unconventionally, not as its usual narrative of bringing about efficiency or productivity for the benefit of humankind, but to conceptualise alternative perspectives on it. Naturally, as part of thinking about these alternative perspectives, the ecology comes into play as the two interact frequently with one another. I also think the topic of nature is an urgent and pressing matter for our times, hence I choose to tackle it.

What are you working on next?

I’m actually working on a radio play titled The Right To Do Nothing, about imagining a scenario where migrant domestic helpers are paid to do nothing. I’m also attempting my first feature film based on a short story in Indonesian literature in the 60s, and it will once again have the threads of myth making and so on, but it’s still in the works. I’m hopeful about it though, as it would be like a dream come true for me.

People on Sunday and Tellurian Drama are currently in competition at the Silver Screen Awards. Catch SEA Short Film Competition Programme 3 online on The Projector Plus.