All images courtesy of Rita and Llewelyn unless otherwise stated.

Rita Ahmad, 47, was queuing for food at Pasir Ris a few weeks ago when a Chinese boy in his 20s shyly asked her: “Is the Chinese man sitting there your husband?”

Rita nodded.

“Can I ask how his parents accepted you?” he continued.

Acting on a hunch, Rita ventured: “Your girlfriend Malay ah?”

“Ya. And my parents cannot accept it,” the boy answered.

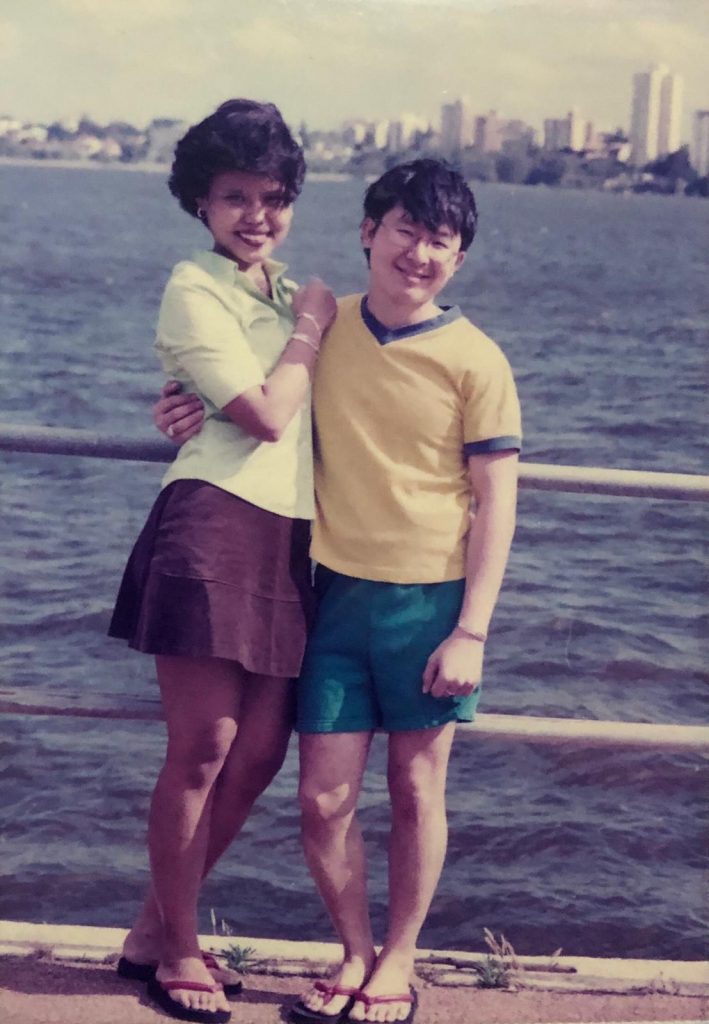

For the briefest moment, it was as if 28 years melted away and Rita saw a younger version of her 52-year-old husband, Llewelyn Ridhawn Teng, standing before her. So much has changed in Singapore, she thought, and yet so little.

But, as Llewelyn admits with a chuckle, “when you work hand in hand with your team 10 to 12 hours a day, you don’t really have a social life outside the airport … so you can’t help but get close to the people you work with.”

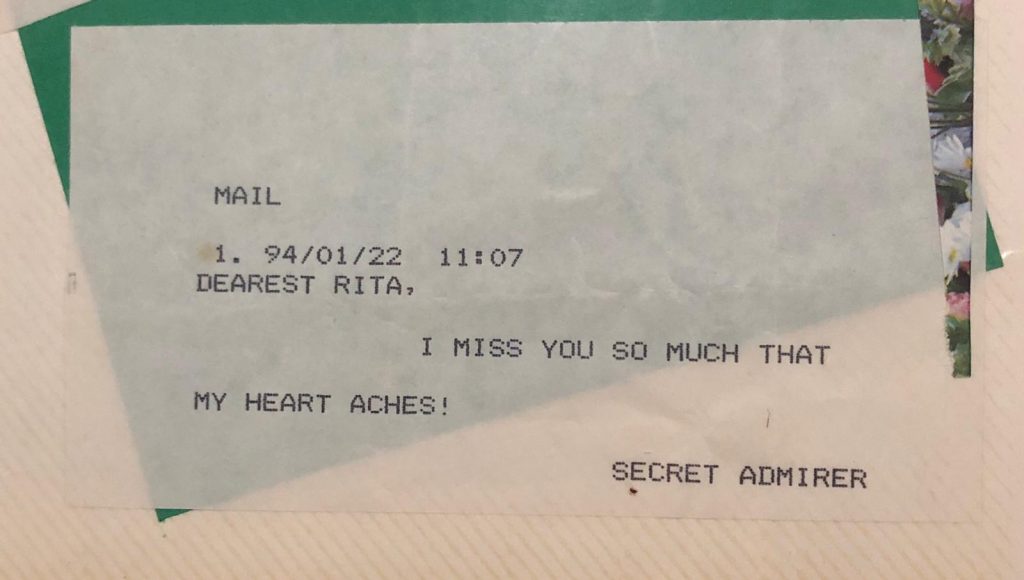

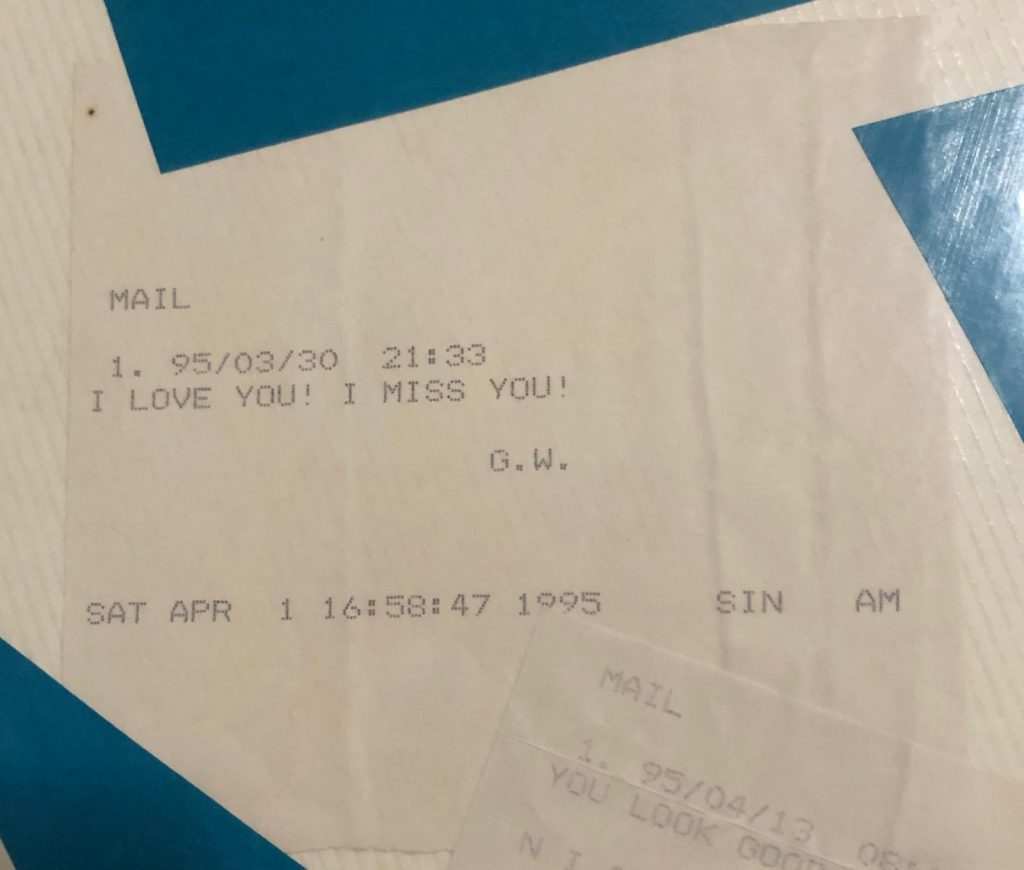

Dearest Rita, I miss you so much that my heart aches! Secret Admirer

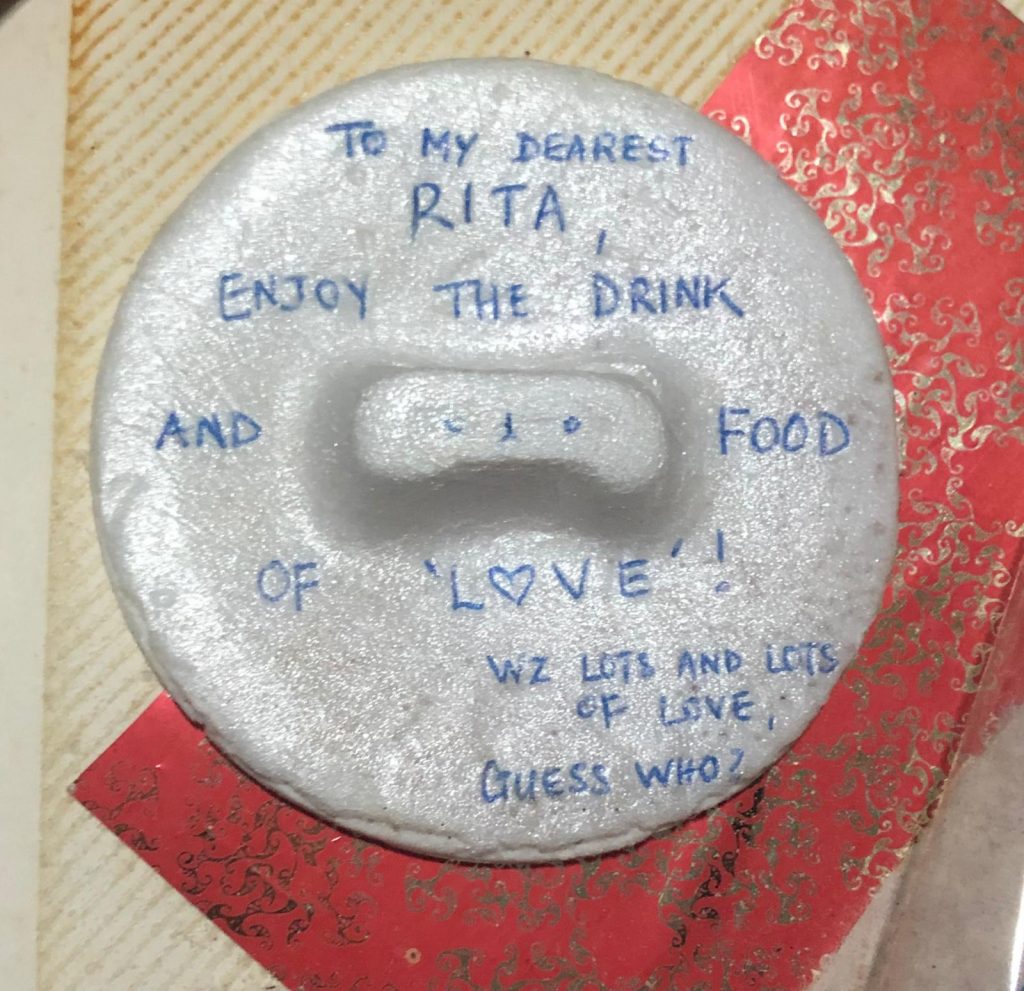

To my dearest Rita, Enjoy the drink and food of ‘l

“I was so naïve,” Rita giggles. “I told Llewelyn, ‘Eh, someone is into me.’

“But he was also such a good actor. He said, ‘I help you check who’s the person.’”

The rest, as they say, is history.

History, however, tells us that Rita and Llewelyn’s relationship is not as common as we may think.

In 1994, only 8.8% of all marriages in Singapore were between couples of different races. Low as that figure seems, if we go back another 10 years to 1984, it drops to 6.3%—and the downwards trend continues the further back we go (at least in terms of officially recorded statistics on interracial marriages).

One reason for the low rates of interrmarriage may be explained by the cultural traditions of each racial and religious group.

In the research paper “Ethnic Outmarriage Rates in Singapore: The Influence of Traditional Socio-Cultural Organization”, sociologists Riaz Hasan and Geoffrey Benjamin explain that “Indians expend much effort in ensuring that their daughters marry properly” because “in Hindu-Indian belief … it is maternity … that determines a person’s ritual (and hence social) standing.” Therefore, an Indian woman’s marriage prospects might be tightly controlled by her family, preventing her from marrying out of her caste, let alone race.

For the Chinese, patrilineage, that is, the passing on of family kinship through the men, influences marriage decisions. In contrast to the Hindu-Indian belief, it is the Chinese man whose “behaviour as regards marriage is … circumscribed by family control”. As a result, “approximately five times as many Chinese women marry out as Chinese men”.

Contrarily, interracial marriages between Malay and Indian people—if both share Islam as a religion—are relatively higher than the average in Singapore because “Islamic allegiance in itself has an overriding and equalizing effect”. Indeed, almost half of Indian-Pakistani immigrants to Singapore married out of their race in the 1960s because of religion.

When Llewelyn’s mum found out that he was courting a Malay-Muslim girl, she grew furious. “There was a lot of disapproval, anger … lots of tension at home,” he says. “She knew that if I got married to her, I would have to convert.”

Thus, his mother went out of her way to express her unhappiness, and even tried to drive a wedge between Llewelyn and Rita.

“When I go to Llewelyn’s place, his mum will just look away and pretend I’m not there, that kind of thing,” Rita recalls.

“And when he calls me from his house, I cannot hear what he’s talking about, because his mother will pick up the other phone and place the receiver at the radio. So he had to use a phone card to call me from a public phone.”

That’s not all: when Llewelyn returned home after talking to Rita at a payphone, he would find himself locked out of home.

Like a good general, Llewelyn’s mum also mobilised the whole family against him. “My mum is the matriarch of the family,” Llewelyn says. “Whatever she says, the whole family has to listen.”

“That time, she said no, so his family didn’t accept me, not even as a friend,” Rita adds.

“I believe that my younger brother and sister may have been more accepting of Rita, actually,” Llewelyn clarifies.” But they could see how unhappy I made my mum during that period. So they backed her up. They rebuked me, argued with me, tried to knock some “sense” into me.”

Things got so bad that Rita told Llewelyn: “If your mum cannot accept me, then there’s no way we can be together”.

Despite the conflict with his family, Llewelyn does not blame them. “Religion is not something you can take lightly,” he reflects. “Especially when you are going to spend your life with someone not of your religion [and race].”

Neither does Rita think that Llewelyn’s mother was mainly motivated by racial or religious prejudice. “Religion is one thing. But I think my mother-in-law was just thinking ahead then—wanting the best for her son, making sure both of us were serious. As parents now, Llewelyn and I understand that’s what parents want for their children. So I think that might have been why she was not accepting of our relationship.”

In 1996, Llewelyn’s family moved to Tampines. One of the first things his mum did was to invite Rita over.

Re-enacting her surprise at receiving the invitation from Llewelyn, Rita exclaims: “She invited me? Really?”

When Rita arrived at their new house, it was only half-furnished, but Llewelyn’s mum personally gave Rita a tour of it and described her plans for decoration. And at lunch, she brought Rita to a Malay stall, saying, “This Malay stall is very nice. You should try.”

“I think she was trying to open up to me at that point,” Rita reflects. “I guess she realised her son was serious about me.”

After that invitation, the couple’s relationship with Llewelyn’s mum took a turn for the better.

“My mum doesn’t cook pork at home anymore,” Llewelyn says. “She’ll only eat it outside. During Chinese New Year gatherings, they will prepare separate dishes and go out of their way to accommodate us.”

Rita agrees, saying that and she now looks forward to celebrating Chinese New Year with her in-laws. While she enjoys learning about Chinese culture from Llewelyn’s side of the family, such as picking up auspicious greetings (e.g. (新年快乐) from Llewelyn’s dad, food, she admits, also plays a big role in her enthusiasm.

“Llewelyn’s grandma will cook many Peranakan dishes like ayam buah keluak, itik cooked in kiam chye, crabmeat balls with bamboo shoot soup … and of course sambal belacan,” she effuses. Of course, she will bring along goodies that her family bakes, like her grandmother’s pineapple tarts and kueh makmur.

For Hari Raya, Llewelyn and Rita will coordinate their outfits and “wear baju kurung of the same colour”, she laughs, with Llewelyn completing the look with a songkok.

Most importantly, these festivals present an opportunity for “family members to be together”, Rita says.

Rita is especially grateful about her relationship with her mother-in-law: “When we got married, my mother-in-law helped us do everything. She searched for houses with us, went to look at the houses together …

“During our Malay wedding, the make-up artist sucked,” Rita laughs. “The make-up was really …” Apparently, it was so bad that Rita was at a loss for words.

But in this moment of levity, Rita suddenly took a piece of tissue and dabbed at her eyes, catching me off guard.

“My mother-in-law knocked on my door and told me, ‘Whatever it is, you still look pretty.’

Rita gushes: “From a person who does not see me to a person who goes through thick and thin with me … She’s my best friend now.”

“My mum, she’s Peranakan, so she can be a bit stubborn. But I take after her. I can be just as stubborn.

“Whether my mum accepts our relationship or not, I would have gone ahead. My mind was set. I was prepared to be ostracised by the family.”

Was there anything that the couple did, in particular, that swayed her decision?

“Not that I can recall,” Llewelyn replies. “I didn’t really … try to convince my family much.

“I just took it as per normal. Rita was just another human being, you know? Rita was just a woman that … some day, I want to get married to.

“After two years of courtship, my mum realised I would not let this girl go. So she accepted it.”

This steady upward trend of interracial marriages may suggest very promising things about Singapore society. Sociologists understand “marital assimilation … as signalling the final breakdown of social barriers between groups”. Indeed, Sharon Mengchee Lee, author of the paper “Intermarriage and Ethnic Relations in Singapore”, acknowledges that “some who marry out of their ethnic communities may indeed be creating ties that will eventually contribute to more extensive and intimate intergroup relations”.

The couple agrees that this trend may reflect the growing acceptance of interracial marriages in Singapore society.

“I suppose in Singapore our society is more … tolerant of such marriages, from what I see and hear. On my side of the family, I’ve got a few mixed marriages as well. The group of people who don’t eat pork during Chinese New Year is always growing,” Llewelyn says.

“It’s everywhere,” Rita chimes in. “Society is more open to mixed marriages now. One of my cousins followed in my footsteps and married a Chinese man.”

While this picture is rosy and appealing, it is too early to surmise that Singapore society is maturing into a racially progressive one based solely on this data. People who enter interracial marriages may still harbour unfair prejudices against people of other races. Contrarily, individuals not in interracial marriages are not necessarily racist. Statistics on marriage are just too limited to point to any firm conclusions about broader society. “Exogamy,” as Lee writes, “has many and potentially different meanings for the individual and the aggregate.”

What is clear, however, is that the maturation of Singapore society has to involve compromise and give and take—just as interracial marriages do. “We have to be more giving and not taking so much,” Llewelyn says.

For instance—as Rita mentioned—Llewelyn’s family does their best to accommodate their Halal dietary restrictions. And Rita has always counselled Llewelyn to put his mum before her, to continue respecting her, even as she was deliberately making their courtship difficult.

But the gesture that moved Rita the most was when Llewelyn got circumcised. “To convert is one thing. But to go for circumcision … I didn’t expect him to go through all that for me. It’s a bit emotional,” she tells me, half laughing, half tearing up.

“Surprisingly, his mum was fine with it. After his conversion, she asked him what he cannot eat; after his operation, she went to check on him regularly.”

“Yeah, she’s cool about it,” Llewelyn laughs. “The biggest obstacle is the approval of parents. Once you get that approval … everything should fall into place: prayers, conversion, circumcision.”

“Of course all parents will not accept your relationship at first, because they don’t know if you’re serious enough,” Rita replied.

“What you have to do is show them that you’re serious about it. You will take responsibility. You respect the religion. And you love the person.”

References

Department of Statistics, Singapore. Statistics on Marriages and Divorces, Reference Year 2018.

Riaz Hasan and Geoffrey Benjamin. “Ethnic Outmarriage Rates in Singapore: The Influence of Traditional Socio-Cultural Organization.”

Saw Swee-Hock. The Population of Singapore, 3rd edition.

Sharon Mengchee Lee. “Intermarriage and Ethnic Relations in Singapore.”

This editorial is written in collaboration with Roots.sg and National Heritage Board.

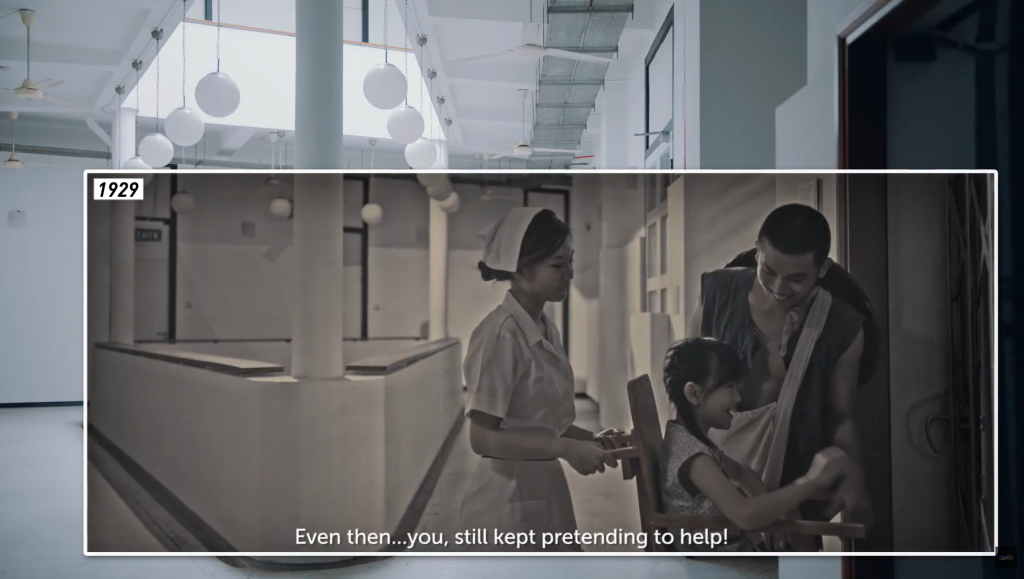

For Your 55th is a story of kind deeds, love and loss. Watch the accompanying tale by NSFTV of a rickshaw rider and a young nurse as they navigate romance in 1929, across ethnicity, class and time:

Do you have a story of interracial romance your own? Share it with us at community@ricemedia.co.