The article describes her experience counselling N, a 22-year-old “Chinese homosexual serving his National Service as a clerk in an army camp”. N was referred for counselling through his medical officer for help in “deal[ing] with interpersonal problems in camp as a result of his effeminate behaviour”.

Lily and N established a “warm and amicable” client-therapist relationship. She writes, “I found N positive and motivated towards counselling.” These sessions, however, seemed to trouble Lily:

“I had wanted very much for N to choose a ‘straight’ life … I was saddened when he chose to remain as a gay after we had explored the challenges he would face as a homosexual. In fact, as the counselling relationship strengthened, I encouraged N to attend a programme for homosexuals, run for the purpose of helping gays change their sexual orientation to one that is ‘straight’.

“I also felt hypocritical when I assured N my acceptance and respect for him, regardless of his decision on whether he would remain gay, when my desire was for him to make a different decision.”

Despite this problematic perspective, Lily ends her article on a positive note.

“I am grateful to N who gave me the privilege to enter into his world of homosexuality,” Lily concludes. “I have learnt much about the homosexual subculture and it had challenged me to review my own worldviews and stereotypes.”

Correction: local forums are rife with speculation and anonymous—hence unverifiable—tales. They range from the closeted pre-enlistee worried about being bullied in the army, to gay men sharing their experiences declaring 302 (the official medical code the SAF uses to classify gay men), to car fanatics who are “scared kena touched in the dark” by their gay bunkmates.

Properly documented reports of what happens when you declare 302, however, are few and far between. The most reliable and oft cited belongs to Lim Chi-Sharn, who meticulously detailed the process of coming out as gay to his medical officer because he, too, was frustrated by “[sketchy] word-of-mouth … information available online” and “wanted to partially fill this lack of publicly available information by documenting [his] own experience”.

Originally published in 2002 on the email group SiGNeL (the Singapore Gay News List), and later picked up by Fridae and Yawning Bread, his account is lengthy and worth reading in full. For those short on time, some things stood out to me:

1. Chi-Sharn’s “officer cadet training … [was] terminated” after he disclosed his homosexuality;

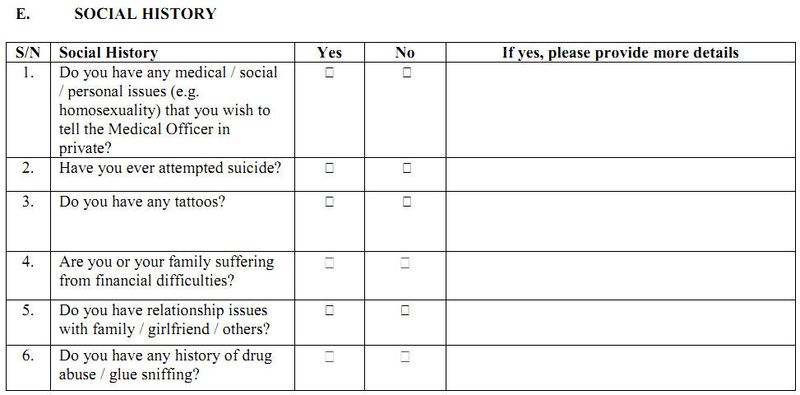

2. Homosexuality is listed as an example of a “social problem” in the medical declaration form (though, in a later version that I found, the phrase seems to have been altered to “social issue”);

3. Capt. Tan, the interviewing doctor, asked Chi-Sharn, “Are you the man or woman?”;

4. Capt. Tan mentioned that ‘sensitive’ areas [in the military] are probably out-of-the-question” to gay servicemen;

5. Capt. Tan told Chi-Sharn that the SAF does not consider homosexuality a mental illness. However, Capt. Tan also acknowledged that the SAF’s “‘Directory of Diseases” contains entries on homosexuality and transsexuality.

The military presents a challenging environment for them, Lily writes—completely without irony—because:

■ It is assumed that gays would threaten discipline and morale

■ It is assumed that the male bonding that takes place in combat would be jeopardised if its potential for erotic contact were condoned

■ It is believed that gays are subject to blackmail in the military context

Seen in this light, the interview by Capt. Tan was designed to assess if Chi-Sharn would pose a problem to the armed forces in these ways, and, if assessed to do so, what vocation would suitably sequester him away from his fellow servicemen.

Granted, these pronouncements are by one woman and do not necessarily reflect the motivations underpinning SAF’s treatment of homosexual men. But we must remember that Lily was the Head of Research and Training Branch at SCC, and was writing for a publication affiliated to the SAF. Therefore, it is hard not to understand her article within the larger context of institutional policies regarding homosexuality in the military.

It is, however, almost too easy to demolish each assumption or belief. All three points are categorically disproven by multiple militaries around the world, such as Israel, Canada, and Australia, which have abolished discriminatory policies towards queer soldiers without compromising military effectiveness. In fact, “British military officials saw an unexpected benefit of allowing gays to serve openly—better retention of qualified soldiers and sailors in key positions.”

Moreover, if eroticism in the army were truly disastrous to its capabilities, then it logically follows that all women should be banned from serving. Yet the SAF constantly attempts to attract women to a military career and celebrate its female soldiers, which is a glaring contradiction to its fear of “erotic contact” in the army. (Just to be clear, I am all for equality in the army, whether it’s gender or sexuality.)

Equal treatment also removes any need for queer people to stay in the closet while serving the military. The freedom to live openly, in turn, prevents them from being susceptible to blackmail: blackmail loses its power when its victims have nothing to hide.

Discriminatory policies based on a fear that “gays are subject to blackmail in the military context”, therefore, create an absurd Catch-22 situation. Soldiers in such armies keep their sexuality a secret because of institutional discrimination motivated by the fact that these soldiers have a secret … It is a circular (il)logic that characterises the contradictions gay servicemen experience while serving NS.

In fact, Lily’s article, “Understanding Homosexual Servicemen — A Case Study” can be accessed only through a snapshot of the page taken by the Internet Archive. It is no longer available at its original URL, which may suggest that the SAF is now more enlightened in its policies regarding gay servicemen and no longer endorses or subscribes to outdated views about sexuality.

“My bunkmates were making jokes like, ‘Do you think there are any gay guys in our bunk? Are they going to rape us at night?’ And my sergeants would say, ‘Run faster! Stop being such an Ah Gua!’

“It felt very tiring … to have to wear a mask. I was already very out, and it felt like I had to step into the closet again … There was [also] a lot of built-up resentment because the first day, [the commanders] try to motivate us by saying things like, ‘Picture your house with your wife and your kids’.”

Expecting the casual homophobia and heteronormativity to persist in the medical centre, Kennede was thus surprised to find the MO being “very chill about it”.

“The MO … told me, ‘I don’t want you to think it’s a mental health problem. I also want to know exactly why this is causing you any problems that you have now,’” Kennede recalls. “I really appreciated that.”

With the support of his PC, Kennede eventually felt comfortable enough to come out to his fellow clerks, who took the news in their stride. Most of them had never met a gay person; their main reaction was fiery curiosity about all manner of gay things. At the same time, they were careful enough not to offend Kennede by bombarding him with potentially sensitive questions. But Kennede opened the floodgates to them.

“I told them I’m very sex positive. They can ask me about whatever,” he laughs.

Encouraged by his experiences in Selarang camp, Kennede decided to come out soon after when he underwent BMT a second time. Now that his section was consciously aware of the presence of a gay person in their presence, no one cracked a single homophobic joke.

“I had a core group of friends in the service who were fully aware … and [provided] a support system at a peer level,” Prashant tells me.

“I came out to my CO and DYCO by email … They know me quite well and were quite positive about it. They were keen … for me to continue working there. At that level, it wasn’t an issue.”

What was an issue, however, was Prashant’s security clearance. Prashant served in a “classified operational unit”, in his words, and thus had to go through Category 1 security clearance. As part of the process, it was mandatory to answer a questionnaire designed to “weed out people who visit prostitutes, who are financially indebted, or are gay,” according to Prashant.

“Because these three, they believe, would subject you to blackmail, and therefore trade national secrets to the enemies,” Prashant speculates, correctly alighting on Lily’s (fallacious) belief that “gays are subject to blackmail in the military context”.

After he declared he was gay in the questionnaire, the Military Security Department (MSD) put Prashant through two full-day, one-to-one interviews in a windowless room.

“It was a very long interrogation process,” Prashant recollects. “Right down to intimate details about your life, who you hooked up with, all these. And then there’s a polygraph test after that to see if I had compromised security while I was away [for my overseas studies].

“The process with the interviews was quite painful. You’re dealing with people who are not familiar with what queer lives are … The burden was on you to try and explain what your lifestyle was.

“Some of the questions were, ‘Do lesbians become lesbians because they have very bad experiences with guys? Do you think you’ll get HIV?’”

In the end, Prashant obtained his Category 1 clearance. When he finished his 3-year stint in his operational unit and was up for his staff tour, however, his homosexuality became a thorny point for MSD.

“MSD [also] gave directions I shouldn’t [come out] to anybody during my staff tour. They said it would compromise my position then.

“And even though my staff tour bosses were putting me up for promotions, at some level higher up, it wasn’t happening anymore. I was getting letters that said ‘You’re not meeting your promotional requirement.’ But my bosses don’t know why, because I’m performing well at the staff tour … it was always trying to negotiate this space and trying to pretend you don’t know the reason.”

Prashant’s inability to obtain Category 1 security clearance after he came out, unfortunately, does not seem an isolated case. The 2014 book Mobilizing Gay Singapore: Rights and Resistance in an Authoritarian State by NUS law professor Lynette J. Chua describes a similar scenario:

One activist, Robbie, was a career officer but not a government scholar. After having kept quiet on previous checks, he decided to disclose that he was gay during a routine security clearance. He was ordered to write down the names of places he frequented socially and people he knew. Subsequently, he was blocked from the highest level of security clearance, which he had obtained before; however, Robbie is uncertain whether that was due to his coming out or due to the fact that he had already told his superiors that he did not intend to renew his contract.

The near identical nature of Prashant’s and Robbie’s experiences suggests that such policies regarding homosexual servicemen are widespread, even institutional. Kennede, too, says he knows of officers who were decommissioned for being gay (though I could not verify this information independently).

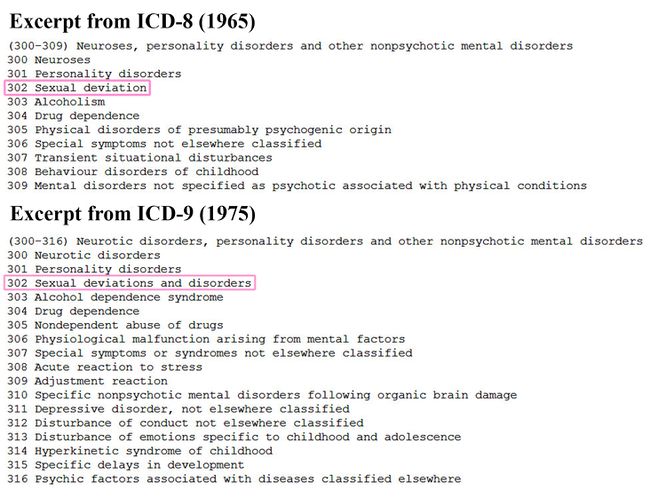

The SAF’s internal “Directory of Disease”, however, still retains its ICD-9 roots, 28 years after the publication of ICD-10. Egregious as that sounds, such medical anachronism in the military is slightly more pardonable when we realise how enormous an undertaking such a migration entails. For instance, as Singapore LGBT Encyclopaedia notes, Singapore’s hospitals only adopted ICD-10 in 2012; it even had to enlist help from the University of Sydney to ensure a smooth transition in what was essentially a complete revamping of its systems and processes.

In other words, it may be possible that these ostensibly discriminatory practices are not motivated by homophobia or malice, but bureaucratic inefficiency that prevent policies from keeping up with the pace of change in the real world.

Prashant’s reflection of his times as a regular serviceman seems to attest to this. “My challenges were more at a bureaucratic level, where there are arcane policies that they haven’t changed, or where they don’t know how to deal with somebody who’s out.

“People were generally quite supportive and open. And it wasn’t a threatening environment,” he concludes.

Kennede agrees: “In that environment, there was no maliciousness at all.”

That said, both Prashant and Kennede acknowledge that they may possess certain privileges that make it easier for people to accept them.

Prashant reflects, “We are in positions of privilege, whether it’s education or passing as cishet [a cisgender, heterosexual person]. [To someone not familiar with queer issues,] we may not be perceived as offensive, as a very effeminate person might be.”

The SAF’s reluctance to let go of ICD-9 also reminds us that progress, sometimes, has to come from the top. Most people are ready for change; those who are not tend to revise their opinions after interacting with a gay person.

But policy-based discrimination legitimises and naturalises hate. It allows hate speech to disguise itself as the defender of an imaginary moral world.

And yet gay soldiers do not choose who to defend. They do not discriminate in their willingness to give up their life for Singapore.