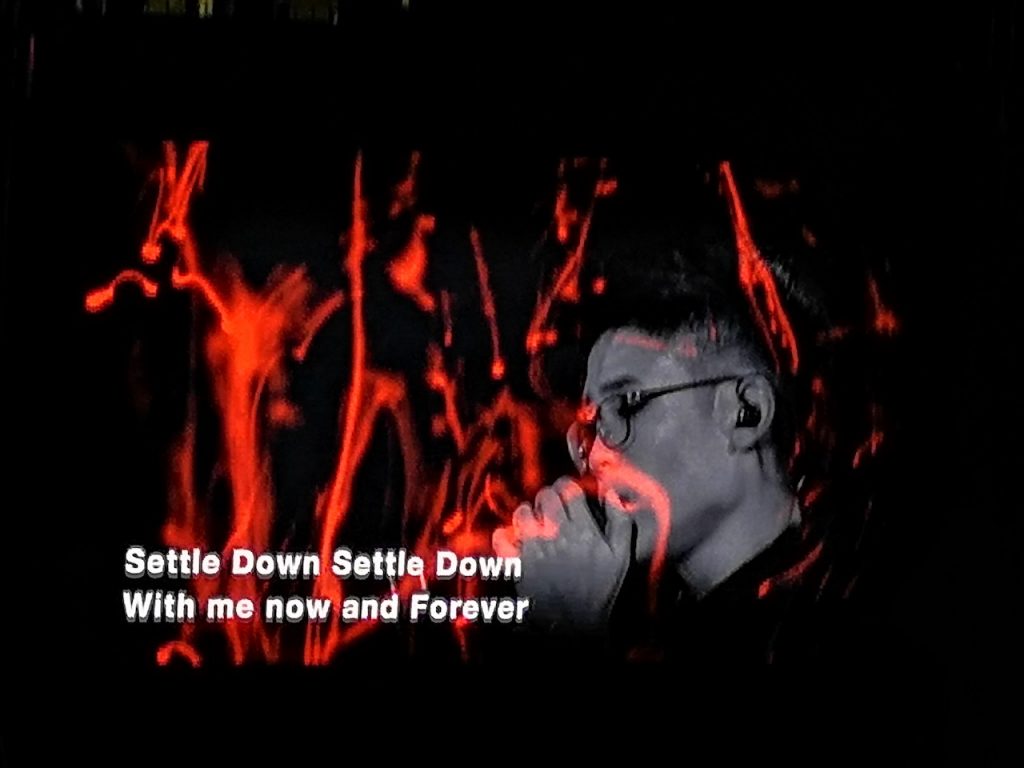

On 15 June, local musician Gentle Bones responded in English to a Mandarin host at the Singapore Cultural Centre’s Cultural Extravaganza, leading to the publication of a Rice Media thought piece on language and ethnic Chinese identity in Singapore. This came in the wake of record-breaking public protests in Hong Kong, which had prompted observers to discuss the subversive role the Cantonese language has played in the demonstrations.

But what does any of this mean for Singaporeans?

At home, older Singaporean Hokkiens pronounce 结婚 (jiéhūn) with a misplaced ‘f’ and a sharper drop in tone (jiè fēn), and Cantonese people stray from official Mandarin standards by pronouncing 白色 (bái sè) with a telltale low-flat tone dip on the 白 (bái).

These happenings are not mere glitches in our region’s chiselled linguistic landscape; they are reflections of our familial histories and the consequences of our nation-building politics.

For a country as young as Singapore, the words we speak and the memories we pass down between generations are direct results of calculated educational and media policy changes. In our bid to facilitate economic relations between mainland China and Singapore, the Singaporean government worked deliberately to erase our native southern Chinese languages, and replace them with a half-spirited “effectively bilingual” education.

They were successful.

These names and official positions are taken to be facts of nature. That Singapore is the only country outside of mainland China that uses simplified Chinese characters is never questioned, and Chinese languages that fall outside this simple perimeter are dismissed as mere dialects.

In other words, Hokkien/Teochew (or Minnan), Cantonese, Hakka, etc are treated only as improper subsets of “Chinese” Mandarin. Most local Singaporeans do not even know that these languages can be written, and the ability to speak these fluently has experienced a sharp drop in the last two generations.

So the adage goes, “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.”

Plainly speaking, the language that commands the most respect is the language that demonstrates the most might. The capital of China has been situated in the north for most of the last millennium. And so, within the context of the Chinese languages, the language backed by the central government in China—Mandarin—emerges victorious.

The simplified Chinese script, which we use today in both China and Singapore, was conceived by the central Chinese government to improve the efficiency of communications and raise national literacy rates. After the Communist Party established the People’s Republic of China in 1949, China had a population which was mostly illiterate. They simplified the characters from 1952–1986 in an attempt to make the learning process easier for citizens.

Singapore, in its own race toward efficiency, underwent a parallel process of simplification between 1969 and 1993. The process began with the Ministry of Education’s release of simplified character charts, and ended with the 1993 update of identification documents. Our eventual simplified Chinese characters were made to match those decided upon in China.

As a result, communications between mainland China and Singapore were prioritised over relations with places like Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, and certain coastal Chinese districts. The Singaporean government settled on a “Use simplified, recognise traditional” (用简识繁 yòng jiǎn shì fán) approach to deal with this disparity.

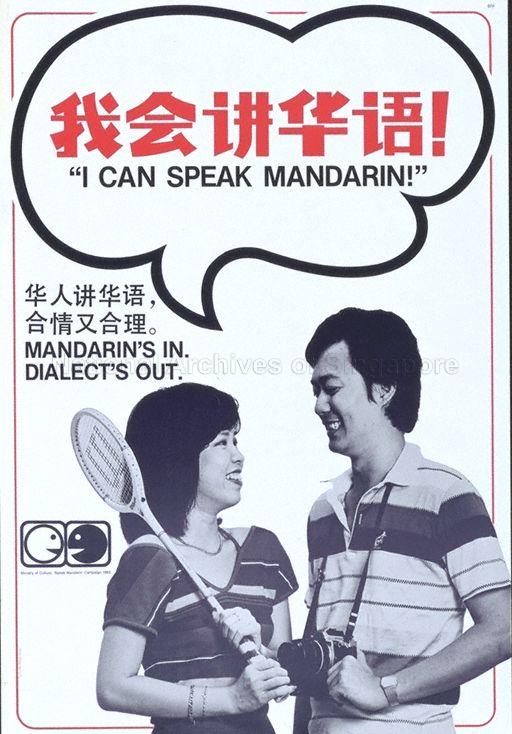

Meanwhile, in 1979, the then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew launched the Speak Mandarin Campaign. At present, the Speak Mandarin Campaign encourages Singaporeans to use Mandarin to cultivate an appreciation of a vague, unified Chinese culture.

The historical television drama Samsui Women (红头巾 hóng tóu jīn) centred the lives of construction workers from the Cantonese-speaking Samsui region of Guangzhou, but the show recorded and aired all the dialogue in clean Mandarin. Up till the present, the Free-to-Air Television Programme Code and Free-to-Air Radio Programme Code restrict the broadcasting of Chinese “dialects”.

Under these codes, media authorities greenlight only special programmes, like opera, to broadcast in non-Mandarin Chinese languages.

Fast forward to the present, and we rarely hear non-Mandarin Chinese languages on the air. We write Chinese documents in standard Mandarin. We teach only Mandarin in simplified characters in schools. Older Singaporeans who remember traditional characters may get along fine with reading material from Hong Kong and Taiwan, but the difference in script is an additional barrier for Singaporean youths.

We have just entered the era where we are losing our last fluent speakers of southern Chinese “dialects”. The flames of our actual ancestral languages are dying. There may well be a day where we won’t hear Hokkien on the streets anymore.

In the spirit of fairness, I must acknowledge that the Speak Mandarin Campaign was an uproarious success. We met all the goals we set out to achieve. Our Chinese population is almost completely literate, we think of ourselves as one united race, and Singapore’s wealth has skyrocketed. Indeed, it is hard to imagine how things could have played out if we had chosen differently in the 60s and 70s.

But there is more to life in Singapore than our endless pursuit of efficiency and KPIs. The erasure of our native languages has left a void in our memories. We have gone from reciting operas to barely mastering a “How are you?”

This is more than a socio-political problem; it’s about family. Young Singaporeans cannot understand their grandparents, and we cannot speak to them about their life stories.

But history is, by definition, knowledge of things that happened. And knowing what happened to us has value. In the most practical sense, if we lose our ability to understand “dialects”, we lose the ability to translate interviews about how buildings were constructed in the 60s. We don’t understand puns and how food and road names came to be. Some of us don’t even know the names of our grandparents, let alone how they came to Singapore. We need this information in our plans for the future. How are we supposed to make projections for the next 50 years, if we’ve already forgotten the last 50?

The idea that the Singaporean Chinese population is one big Mandarin-speaking group is so thoroughly indoctrinated that we don’t sense anything amiss. These sentiments are, however, swelling in the southern coast of China, the 侨乡 (qiáo xiāng) region where our ancestors originated.

On 10 and 11 July 2010, hundreds took to the streets in Guangzhou and Hong Kong to protest state plans to switch Guangzhou’s most popular TV stations over from Cantonese to Mandarin. A similar protest took place on 26 January 2018, when hundreds of Hong Kong students congregated to resist mandated Mandarin tests.

Driven by fear over mainland China’s encroachment on sovereignty and freedom of speech, the largest scale protests took place over the month of June in 2019 to resist the passing of an extradition bill (with crowd numbers in Hong Kong eventually reaching 2 million). These protests are the crescendo after a long period of unease with the central government’s creeping influence.

The struggle that has been extinguished in Singapore is still going strong overseas. What do we do then? Should Singaporeans reignite the fight, or could we rekindle a gentler flame?

If we are serious about remaining connected to our cultural roots, we could use Mandarin as a bridge to relearn our southern Chinese languages. Our education provides us with a promising foundation to build our mastery of Hokkien/Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, etc. The internet presents us with a wealth of information from overseas sources, both formal (newspapers, articles, essays) and informal (vlogs, social media posts, videos, comedy programmes). The technology for online text-to-speech generators is catching up, especially for Cantonese. This would be invaluable for studying languages with multiple tones and contextual tonal changes. Organisations like Learndialect.sg provide Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese classes for young Singaporeans.

In terms of written records, we should make an effort to use consistent systems to sound out words. The most popular transliteration system for Minnan languages like Hokkien and Teochew would be the 白話字 Pe̍h-ōe-jī. Cantonese uses either 粵拼 jyutping, developed by the Linguistic Society of Hong Kong, or Yale romanisation, which was devised by Gerald P. Kok and Parker Po-Fei Huang for a Cantonese textbook.

To quote Dylan Thomas, “Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

We are rapidly losing our familiar and more human sources of knowledge, but we can supplement what we know with our access to information via the internet. It will definitely be an uphill struggle, considering that for many of us, efforts to erase “dialects” have been in effect since before we were born. This is, however, one of the only methods we have to preserve our fading culture and our memory of yesteryear Singapore.

廢事做一個只係識得聽少少、又唔識講嘅人,啱唔啱啊?

Have something to say about this story? Write to us at community@ricemedia.co.