All images from G-23, Ah Ma, Haze, Lighthouse & Karang Guni, unless otherwise stated.

“I find it very hard to film contemporary Singapore. I’ll worry that anything becomes a condo showflat commercial,” Anthony Chen tells me.

This comment catches me off-guard, and I pause to think about Chen’s films. While it was through Ilo Ilo that he made his big splash here, he had already been accumulating a stream of credits with his shorts. They may not have been thematically connected, but there was no doubt that the scenes were Singapore.

How is it that he has been perfecting his craft over the years—with the awards local and overseas to show for it—yet continues to have doubts about capturing the very present; his here and now? When he watched Crazy Rich Asians, it only reminded him of just how dangerous and offensive this undertaking can be.

And this contradiction is key to understanding what being Anthony Chen is all about.

Next to these, Chen’s films resemble a softer-spoken sibling; more evocative than vocal. Ilo Ilo may confront the nuances of domestic work, economic anxieties, and the fault lines of class, but Chen says he can’t start with a headline or thesis.

“I start with the characters, and it grows and grows. What I’m capturing is the truth of personal emotions, social dynamics, how an individual relates to oneself, to family members, to their work, to their schoolplace. When you get these observations well, that’s when you start seeing the issues at play.”

In Ilo Ilo, there’s a scene of a morning assembly languidly reciting the national pledge in its entirety. As soon as it is over, the protagonist is publicly caned onstage.

“Could it be that Chen intends Jia Ler [the protagonist] to be the satirical embodiment of Singapore itself: cosseted, spoilt and entitled?” wrote Peter Bradshaw in his review. “Overdoses on understatement,” remarked another critic.

Yet Chen tells me, as if in gentle retort, “How do you make a film about issues? I can’t make a film about that. I can make a film about people.”

I suspect the idea that one could make no statement might relieve Chen, someone who prefers to make works that are rather than are about.

Making something semi-autobiographical like Ilo Ilo could not possibly have been too analytical an affair for him. There’s the process of separating the extraordinary from the everyday and the brutal from the banal, along with the very fact that they all seem the same until they’re put side-by-side.

“When I get it right, everything else will fall into place,” he says.

But before that comes many messy questions; the emotions to be excavated piecewise, and the feeling of always groping in the dark.

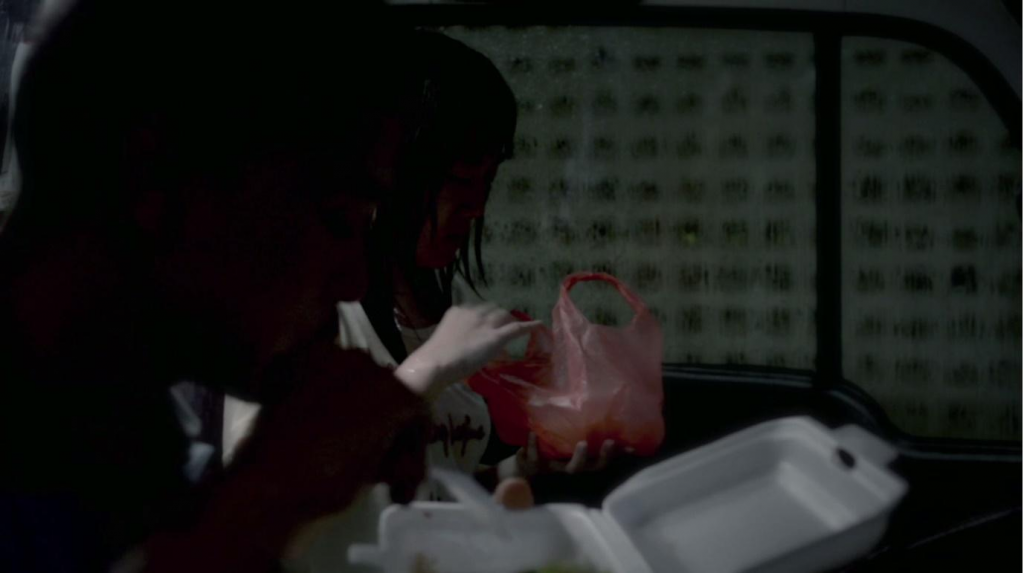

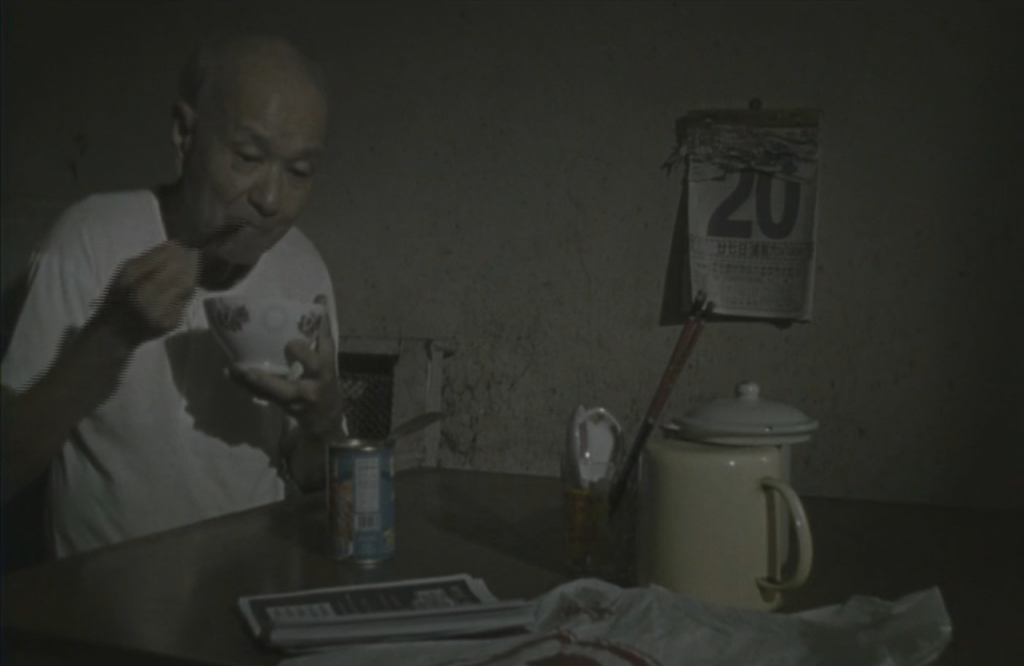

Within a lorry’s front cabin, a karang guni and a Chinese migrant have a Styrofoam-box communion. A teenager figuring out how to use a condom.

Likewise, watching Chen’s shorts feels like walking alongside a montage of people, with opportunities to pause and consume in episodic detail.

He’s fussy on set, and has a reputation for being a stubborn perfectionist. While making G-23, his first short, Chen would grab the camera and shoot by himself handheld sequences that his director of photography wasn’t getting right. He doesn’t take the camera away nowadays, only because most of them have gotten too heavy.

“I now understand what it feels like when Hou Hsiao-Hsien decided to reshoot the whole of Goodbye South, Goodbye three times,” he says.

He also refuses to let his actors to change a single line. It’s not that he doesn’t improvise, but running through his mind is always the urge to “get it right” and “figure it out”—phrases he returns to frequently during our conversation—and use as many takes as required for that to happen.

He also knows he can’t do everything by himself, and lives with the irony of filmmaking.

“It’s completely about control, and the first thing you learn is mise en scène. Yet I can only verbalise and make sense of it to others, and it’s always about questioning the director—himself—and questioning everyone until we understand what this is really about.”

“Every young filmmaker has a Wong phase one has to go through with”, Chen admits, “I’m all over it now.”

He doesn’t have very kind words for his debut, describing it as “rather pretentious”.

At the same time, G-23 is more than a WKW-phase filmmaker’s elegy. It suggests the potential of a ticket-tearer’s curiosity to animate the lives of strangers, going beyond temporary encounters. “There are many questions I want to ask him, but his eyes always tell me he does not speak much,” he introduces one of his patrons. How does one begin to bridge the distance between strangers, separated in degrees and by the privacy of watching a film?

Otherwise, “It’s emotionally wrong for the scene,” emphasis his.

“I shouldn’t feel like that.”

On first watch, I indeed wondered if G-23’s protagonist was a reincarnation of that cop-turned flaneur from Wong’s Chungking Express. But could it also have been the incarnation of a future Anthony Chen? One who could, with a camera, bridge the distance between his imperfect vision and someone else’s truth? What he grasped about those emotions, and what little detail he would embellish it with, came from these questions that he was accumulating.

This also translated into questioning his DP on the way they choose to light something, or questioning directors Kirsten Tan and Tan Shijie, in the capacity of a producer for Pop Aye and Distance respectively. During the making of his upcoming feature Wet Season, he turned those Whats and Whys towards himself, only to break down when the answers would not come (yet).

Its title plays on the yearly affair that’s deeply embedded in our national consciousness, a season of shutting windows and rekindling our anxiety towards the outside. The teenagers nest themselves in their apartment block—a day when behind closed doors and far from school, their adolescent worlds might stand still.

Yet the sensation of encroachment lingers. Backgrounds creep back into the foreground, like the noise of traffic that accompanies them throughout and even during coitus.

As it turns out, Haze has little to say about the big haze. Chen, after all, isn’t as interested in declaratives as he is in staging doubts. And so he turns further inwards, inquiring about the physical and emotional landscapes we inhabit. What happens when they become too absolute to bear?

A teenager lights a cigarette in his house while the news reports a new PSI high. A couple has their first time only to discover the disquieting space between them. Paradoxes and reactions like these fascinate Chen. Instead of gazing up towards the cloud of smog, it’s a time to look at the smaller fires and listen to the sound of our own coughing.

Chen remembered these words as he enrolled into the UK’s National Film and Television School to complete his Masters’, shortly after Haze was completed. If Haze feels like looking into a snowglobe, one crystallising proximity, enclosure and distance all at once, then a parallel set of sentiments also lurked within him—a filmmaker carrying various attachments to home.

Singapore in the meantime was moving on. There wasn’t a casino when he left; when he returned it was right there in Marina Bay and he seemed to be the only one who found it odd. Home was like a mural ceaselessly updating and redrawing itself in concrete and glass.

What if twenty-four frames per second was simply too slow for this amorphous country? Was he to be merely a witness to all of it?

Well, not quite. He found that filming was becoming more navigable and slightly less disorienting at every go: maybe he could have everything figured out after all. As grew certain of this, he took a headlong plunge and began recollecting the autobiographical details of his first feature Ilo Ilo. No longer groping around in the dark, instead tripping around in a dimly lit closet.

Thank god he was in the UK, he maintains. Ilo Ilo could have easily been an “awful kitchen-sink drama”—“you smell those, and you get it already”. He is certain it would have been that had he remained here.

“Most people have this idea that they need to be in the heart of the situation, they must find it there. But I fear I’ll indulge in the wrong things.”

Lighthouse resumes the magnified relationship study Haze left off, circling a single mother as she takes her three children on a road trip. They stop at a landfill to trash their absent father’s belongings. They look for a lighthouse, only to grapple with unclaimed baggage between them. If Haze was a snowglobe, then Lighthouse is the aftermath of a star bursting, tracing emotional matter after it’s dispersed across expansive cornfields.

The core of it is unmistakable: questions beget detail, which beget even more questions. It’s also reflected in the film: objects like the father’s old sock resurface as disarming curiosities, but in the process initiate fresh ruptures. I tell him that there’s a lot of continuity between Lighthouse and his earlier work, and Chen says I’m not the first to observe it.

In fact, why shouldn’t there be?

“I don’t actually think people view me as a filmmaker in the UK. Most people probably think I live and work out of Singapore,” he says. He still directs and produces a lot of work back home, and helped found the production company Giraffe Pictures, which he still runs out of Singapore.

For all intents and purposes he’s still based in the UK, and if he is going to paint in a different neighbourhood, there are things to learn.

“If you want to shoot English or British people and society, you have to grasp the nuances of class. For example, there is a very specific kind of working class that Ken Loach films are all about.”

That precision is vital: “The detail gives you the period, the class. The character’s background, how they speak, how they act.” This only whets his appetite. Many people ask him why he insists on all that detail.

“That gives you the truth,” he simply says. After all, he’s a painter at heart. His upcoming projects include his first British film, none other than a period drama set in the 1970s and spanning forty years.

While anyone will tell you that that is of course not the point—yes, you’re paid in exposure, but it’s Cannes—or that plenty of other awards come with money, the fact is that it’s not enough. He maintained a small income making commercials and commissioned gigs, but quickly went into deep debt after returning from the UK.

He told his wife before making Ilo Ilo: “I’m sick and tired of being this poor.” He had enough of giving up all his savings for the things he loved. He was done with putting the prize money he had into making yet another short—essentially the filmmaker’s equivalent of living paycheck-to-paycheck. And remember that filmmakers are people who look for their own paychecks.

“What is there to prove anymore. People give grants to nurture new talents, and I’m considered old by their standards.”

Nobody likes to talk about money in their art, but he couldn’t ignore the fact that it might be his time to leave the nest.

Ilo Ilo would be his last go. It was something he had been keenly feeling with each new short. There were still the burning questions he wanted to solve, but what he needed at this point wasn’t even answers, merely the faintest acknowledgement.

“I thought, after this I’ll just go into the civil service or go teach at a film school.”

“You realise how much more commercial the feature film world is. It’s not thriving, but there is a certain market even for arthouse and independent films,” he says, describing the difference between the world of features and shorts. He doesn’t mean his comment pejoratively; after all every film has the right to make money. But otherwise, finding money does not trouble him anymore, and he’s just about done talking about it. That may sound like a luxurious thing to say, but this has more to do with the savviness he picked up during his time as a producer.

Nowadays, he only worries about making a good film, as well as getting to the bottom of things that don’t work and don’t make sense. If he is being tormented, at least it’s by his own questions and not money.

If reality is what’s here and now, then he doesn’t think he can make a film about that.

“I’m clueless about what is going on here sometimes—why is Singapore like that? Why can things be so messed up?”

His films may appear contemporary, but like murals, they’re not so much concerned with the sense of place and time as they are about the people who simply share them.

I ask him if he would try shooting a documentary. He would love to, but he says he doesn’t know how. He’s been on juries where he’s had to view many of them. When he was in the UK, Stephen Frears once told him, “Give me a bunch of actors and I can give you a film. But I have no idea how to make a documentary.”

And for someone whose filmmaking thrives on humble questions, that notion of a big reality might hardly be useful. Answers which are too all-encompassing, such that they become a non-answer. Generalisations which feel brash against delicate situations, and have the subtlety of those condo showflat commercials Chen is wary of. If he feels clueless and helpless towards the here and now, how could he attempt to arrest it on screen?

“Sometimes I can’t even smell the truth of life here,” he says. “There’s almost an artifice to things in Singapore.” But he knows what he can do instead: dramatise, ask questions, figure it out.

He once mentioned being most moved by a scene from Ilo Ilo, when husband and wife come clean with their lies: his joblessness, her financial naivete. In their wordlessness, that is truth. They listen to the sound of their unborn baby: truth.

In Ah Ma, a boy encounters death possibly for the first time as he stares at his bedridden grandma. In his agape mouth: that is also truth.

“Truth is a perspective that’s curated. I can give you truth that you feel is much truer than life, even though it’s all fiction.”

Chen’s camera might see it more clearly than he ever could, and he’s okay with that.

Nine short films and a feature is hardly enough to tell for sure what Chen is capable of. Only time will tell, and it’s a mantra that works true for Chen. He brings up Edward Yang, a director he has long admired.

“If you’ve seen Yi Yi (Yang’s final work), you’ll also see that he had to go through love, marriage, childbirth, divorce, all of it, before he could make a film about that.”

Sometimes, these answers feel too minute or too coarse for the question. Other times, it’s the question that doesn’t seem right.

Yet no answer seems to come too late for him. After all, the semi-autobiographical films that took him to Cannes—Ah Ma and Ilo Ilo—took two years and a childhood to recollect respectively.

When that happens, he knows exactly what to do.

This year, it takes place over 12th and 13th July. Register for Spotlight: Anthony Chen here.