Our Prime Minister concurs! At a recent Forbes panel, he argued that HK’s five demands were not meant ‘to solve Hong Kong’s problems,’ but ‘to humiliate and bring down the government’.

Subtext: This is not a rational answer, but a spiteful reaction.

By examining Hong Kong’s history, Mr Dapiran comes up with an interesting counter-argument: 1. Hong Kong has a long history of protests, demonstrations and riots 2. They actually work.

In other words, the protests are a tradition rooted in pragmatism.

To make his case, he takes us on a guided tour of dissent in Hong Kong. Contrary to popular opinion, HK civil disobedience did not begin with the Umbrella movement in 2014. Although it was the most widely-reported demonstration up to that time, it was neither the first, nor even the most successful protest.

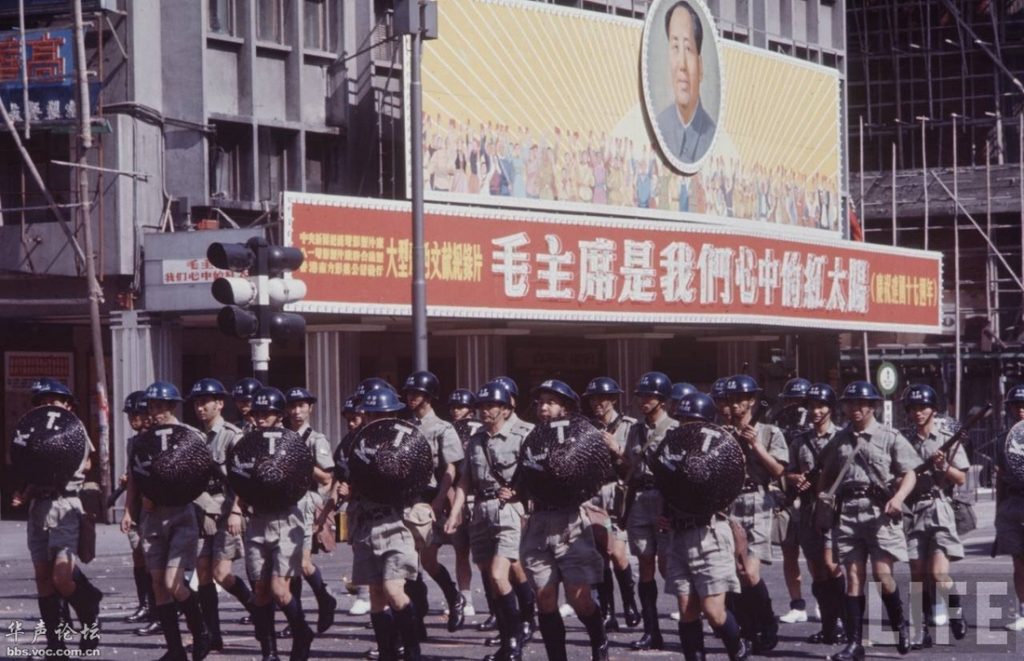

The city has always been staging protests, sit-ins, demonstrations and vigils. Before the Umbrella movement, there was the 2011 National Education Controversy, the 2003 ‘Article 23’ marches, the 1989 Tiananmen vigils and the 1967 Leftist riots, which were instigated by CCP agents sent by China.

In that same year, a small group of protesters marched on the Japanese embassy to protest a Pokemon name change: The mandarin form ‘Pikaqiu’ is unacceptable. Please change it back to the Cantonese Bei-kaa-ciu.

This is a totally frivolous example, but it highlights an important point. Hong Kong has always enjoyed a vibrant protest culture, which began way back in 1966 with the Star Ferry riots.**

In 1966, the Star Ferry Company wanted to raise the fare by 10 cents. Since the MTR was still a twinkle in some urban planner’s eye, this was disastrous news for the working poor, who could not walk on water and had no other means of getting across the harbour.

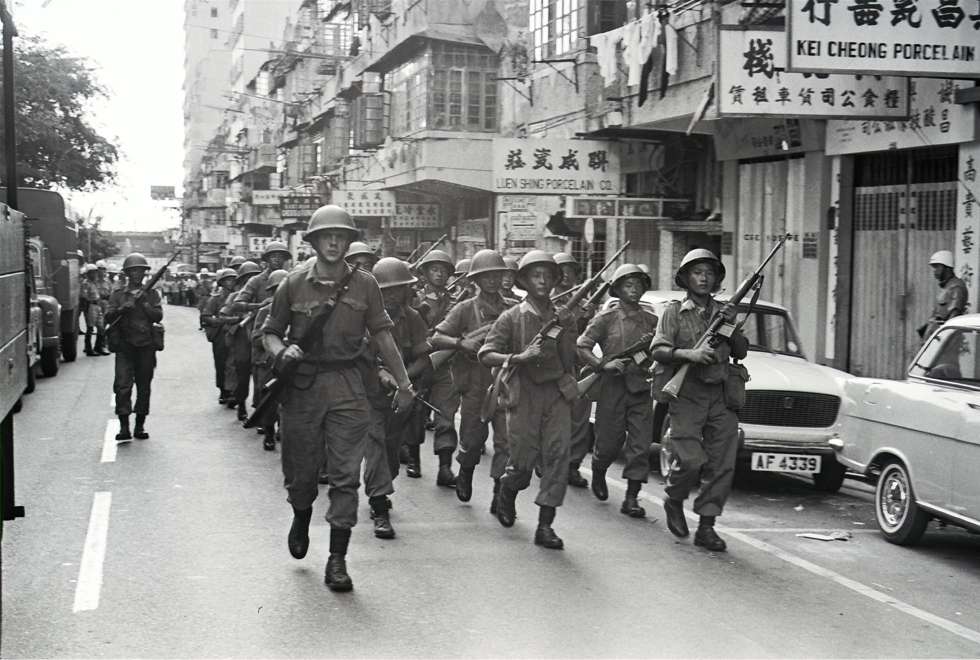

Outrage ensued. A young man, Mr. So-sau chung, started a hunger strike at the ferry terminal in protest. When he was arrested, more protesters showed up to demand his release. When those protesting his arrest were also arrested, all hell broke loose. 1465 people were arrested, 26 were injured and one person was dead. The British Army patrolled the streets to enforce a curfew.

This brings us to the book’s second point: Protests do work. In HK, they are extraordinarily successful as a means of resisting unpopular government policy. Colonial governors and Chief Executives alike were forced to change course when confronted by mass mobilization.

This was the result of the Star Ferry riots in 1966, and it would be the same for 1967 leftist riots, the 2003 ‘Article 23’ marches, 2006 Star Ferry demolition protests and the 2011 National Education protests. Not all protests were successful, but there were enough successes to justify optimism.

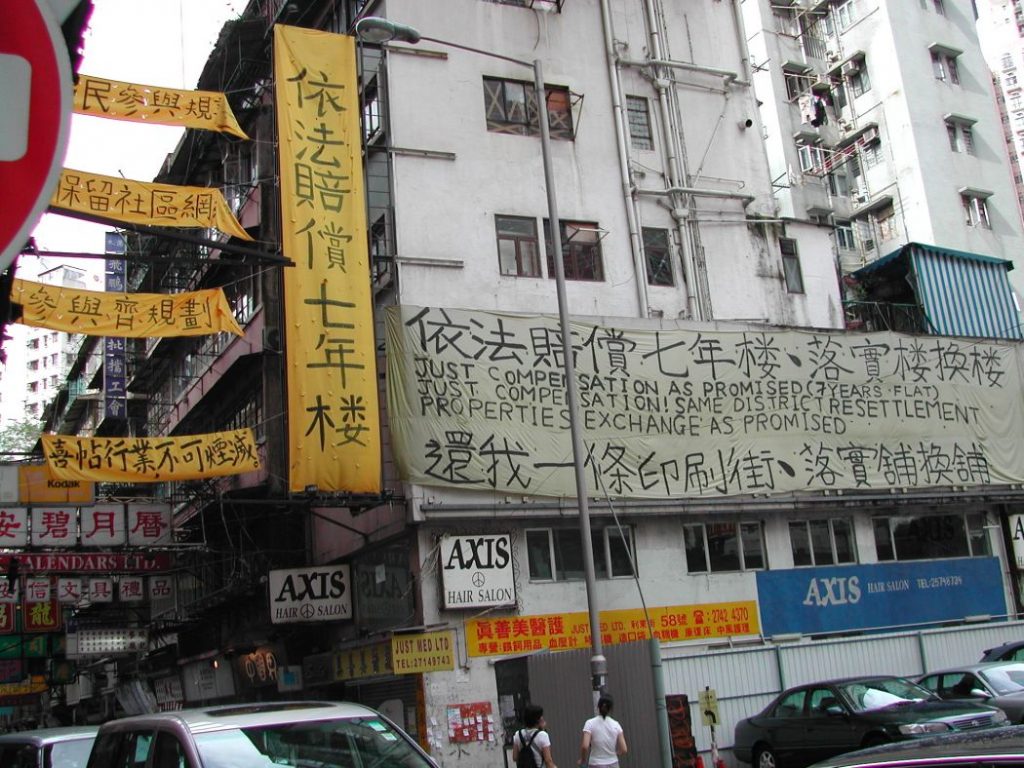

44 years later, protests proved just as successful when the HK govt tried to introduce ‘The China Model’ curriculum, a sort of pro-China moral education program which derided democracy, liberalism and other western opiates. When 120,000 people took to the streets and with university students started camping on Chief Executive C.Y Leung’s front lawn, the HK government gave in. The schools could choose their own syllabus.

Hence, City of Protest makes a simple argument for why Hong Kong is in turmoil: “it often works”. To say that protests will achieve ‘absolutely nothing’ is absolutely misguided because they’ve proven highly-effective as a means of cockblocking unfavourable legislation. This is Mr. Dapiran’s ‘pragmatic explanation’. Given its track record and Carrie Lam’s withdrawal of the extradition bill, I don’t see how to argue otherwise.

Mr. Antony Dapiran calls this system ‘Liberty without Democracy’ and argues that it is the source of HK’s protest fetish.

After all, he asks, why bother voting when ‘past experiences in Hong Kong have shown that demonstrations in the streets were indeed a more effective means of achieving change than participating in the political system?’

His book The Struggle for Democracy in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan argues that suffrage cannot be achieved in Hong Kong by protest alone. Although they’re effective as a means of cockblocking the Chief Executive, they actually hurt the protesters’ cause in the long run.

Looking at the same period of history, he suggests that Hong Kongers protest because the British colonial government was ‘highly responsive to public demand for reform’. In doing so, however, it attracted citizens towards mass protests, and away from ‘membership-based political parties’ like, say, The Tories or The PAP.

This does not seem like a big deal for Hong Kong’s already-spayed LegCo, but Prof Fulda argues this is bad because political parties are important even in the absence of full democracy. They offer the people a means to power because political parties are able to ‘amalgamate and accommodate diverse interests.’

In other words, protest alone cannot forge common ground between contentious parties or erstwhile adversaries. Hence, their potential is severely limited as compared to political parties, who can compromise between ‘striving for ideals’ and ‘coalition-building.’ And in doing so, they build a broader, more coherent platform for political opposition.

To substantiate this argument, the book looks to Taiwan. In the 1970s-80s, DPP lawmakers worked with the KMT government, using ‘trojan-horse’ tactics to slowly liberalise the party from within. Democratization in Taiwan was possible, Prof Fulda argues, because of the’ infusion of young and open-minded Taiwanese politicians into the mainlander-dominated KMT’.

Such a process of ‘reform from within’ could not be achieved by protest alone.

In HK, the preference for protest over parliament has resulted in the fragmentation of the anti-Beijing camp into what Prof Fulda calls: ‘an ever increasing numbers of pan-democratic political parties, which very often resemble NGO start-ups without a clearly defined constituency.’ Instead of ‘unity’ to counter Beijing’s Xi’henanigans, opposition has broken up into a thousand harmless splinters.

In that sense, Hong Kong’s protesters are highly pragmatic. Their methods have worked in the city’s past, and they continue to be super effective today. You could argue, of course, that they hurt Hong Kong’s branding as a financial hub. But that’s disingenuous because you’re judging the protests based on what you want, rather than what the Hong Kongers desire for themselves. It’s a bit like hating Arnold’s because you prefer fish.

Neither book offers a real answer to the bigger question of how to achieve universal suffrage, probably because the real answer will start World War 3, but their history is nonetheless an interesting read. Public opinion either venerates the protesters as saints, or cast them in the role of antichrist. When you look at the history, you realize the civil unrest is not even particularly new or radical. No wonder Lonely Planet lists ‘protest culture’ as one of the city’s attractions.