All images by Isaiah Chua for RICE Media.

On the night of my birthday earlier this year, I decided to make an impromptu trip to Woodlands Memorial to pay a visit to my late grandmother.

I live in Geylang, so ‘twas a long commute. To be honest, I was quietly questioning myself about what spurred this spontaneous trip while waiting for the train.

Was it the grim reminder that I’d just turned a year older—a year closer to reuniting with her? Or maybe it was something more instinctive: enough time had passed since my last visit, and I missed the way her presence always fills family gatherings and birthday celebrations.

The location of the columbarium made nighttime visits troublesome. Not only was it located deep within Woodlands Industrial Park—surrounded by metal factories and distribution plants—it was also plagued by the faint whirr of engines and poorly lit roads, making the journey on foot slightly unnerving.

I was aware of this, of course. The rumbling of the train to Woodlands North MRT station drowned out any thoughts of turning back at 6:45 PM.

But tonight felt different. Special, even. As I reached the columbarium, paid my dues, and spent some time with her, I found myself drawn to the strangely beautiful nighttime landscape outside.

Towering industrial blocks—stoic, unfeeling, distant. Their utilitarian silhouettes carved into the heavy darkness. In this stillness, I found a kind of quiet that grief rarely allows anywhere else in Singapore.

I put my phone away, step into the chilly night, crossed the road, and just started walking.

Walking in Woodlands

The street lights were bright but sparse. They light the pavements sparingly, beckoning me to think twice before exploring further. I dismissed the doubts and started trudging down a random street.

I sought silence and solitude to reflect on death, but the streets had other plans: life unfolding in quiet corners. Migrant workers lined the concrete curbs, backs pressed against fences. Some sought relief from the humidity, stretched out on patches of open, breezy grass.

From somewhere nearby, a TikTok video played softly. Others spoke into white earpieces, their words foreign yet familiar in their warmth—calling home maybe, or just trying to feel a little less far away.

I weaved through the roads, avoiding eye contact—not out of anxiety, but out of quiet respect. I didn’t want to intrude on their pockets of peace. They looked at ease, more at home on the pavements and grass patches than I felt in my own skin.

Labouring so far from home, I assume the same emotions of longing, doubt, and fear plague their thoughts from time to time. We weren’t that different.

They were countries apart from their family. I was worlds apart from mine.

I stride past a number of workers still wearing their construction site uniforms, sipping on tall cans of beer. I can’t help but think: How much better would my life be if I’d just be content with what I had, worry less, and spend more time with the family I have?

I turn onto an ominous street populated by parked towering trucks. I was sure I was lost.

Where does one go to be alone in Singapore?

In an age where every transient safe haven is “ungatekept” by social media, it seems that every obscure fortress of solitude has been conquered.

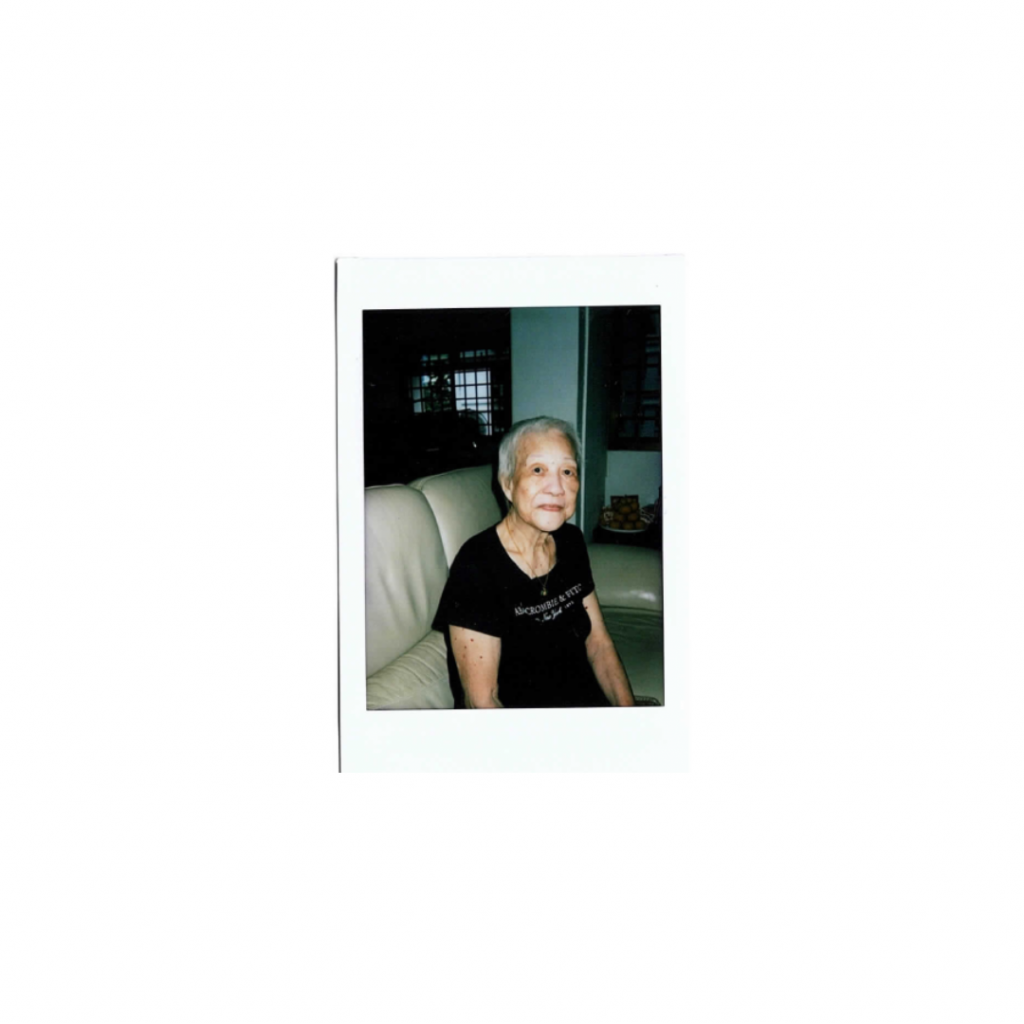

Woodlands has always been a wonderfully sentimental place to me, even after my grandmother’s passing. As long as I could remember, she lived in Woodlands, near 888 Plaza, where she first introduced me to coffee.

Thanks to her, I discovered my love for ngoh hiang; it was hers that ignited it, of course. Her house was also where we had most of our reunion dinners.

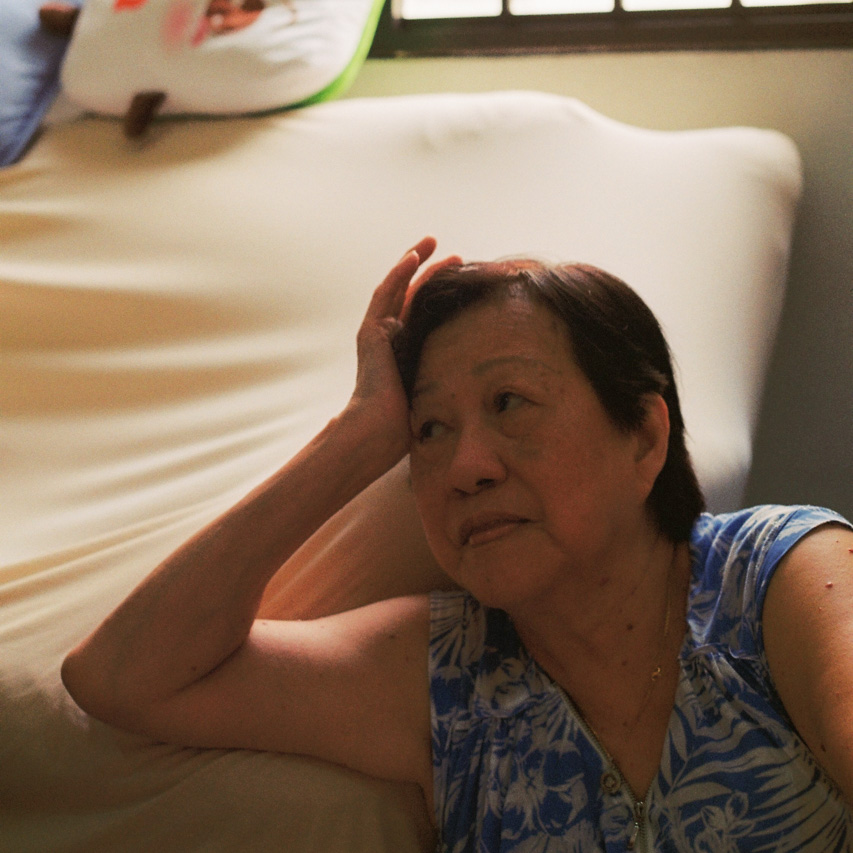

The memories began to rush back. Even near the end of her life, she could always force a smile and throw out a witty joke that made everyone chuckle.

I yearn to experience those moments again.

The thoughts spur me to continue walking down a sketchy road. We were, after all, still in Woodlands. I had nothing to fear here.

Two Years Since

The incessant drone of what I assumed were generators kept me from moping in silence. The hum of output and productivity, a reminder that quiet and stillness are a luxury this country seldom affords.

How do other Singaporeans process the same swirl of emotions I was sitting in?

Maybe it’s escapism—going on a vacation in distant places to chase temporary utopias. Maybe it’s avoidance—throwing themselves into work to distract themselves. Maybe it’s surrender—confiding in a higher power when no one else can.

Grieving is ultimately sentimental and personal; no one should tell you how to spend your time going through it. Which was why being stranded alone in an unfamiliar place felt so peaceful. In this moment, I had all the time in the world to mourn.

It has been two years since her passing. My parents visit my grandmother’s niche with my aunt whenever her death anniversary rolls around—they’d always dedicate a whole afternoon (sometimes a whole day) to adorn it with flowers.

Many grieve by gambling and getting drunk during funerals. Others break into chants or silent prayers, murmuring their hopes for their loved one in the afterlife.

The sound of two tipsy men talking loudly jolts me back to reality. I remind myself that grief is a subjective experience. Who am I to judge when we all find comfort in different ways?

Time Moves Faster Than You Think

Two hours had gone by, just like that.

A bright red plastic bag catches my attention. It just turns out to be a bundled collection of crushed beer cans. A sign that someone had just been here, maybe too intoxicated to find a bin.

In the distance, I spot a few moving vehicles. For an industrial park past dinnertime, it suddenly seemed awfully busy.

What I thought was a very slow motorcycle turned out to be someone on a bicycle. It was an auntie pedalling a dingy bike with a bag attached at the rear. She seemed determined to rush home.

The rickety bike edged forward, groaning with eerie creaks, its sound blending with the hum of machinery in the background.

The sight, as random as it was, sent me into an unexpected daze. It reminded me of the passing of my schoolmate, who was also set to have his ashes placed in the same columbarium as my grandmother.

He was a friend; I worked with him in our university’s student council. But a freak road cycling accident with a truck changed everything, and he passed away during our summer break.

He was about to leave for an overseas exchange. He was only 25.

I never had the time to grieve my friend’s passing. The loss came suddenly, and life pulled me back into routine before I could properly process it.

But grief shouldn’t be rushed or hidden. It’s not a weakness, not a waste of time. It deserves to be sat with—even on this random jaunt at Woodlands Industrial Park.

I looked up. The sky was split—majestic blue in some corners, bruised purple in others. It felt like the sky was painting them in colour before I could name them.

Worlds Apart

As I began to lose sight of the towering columbarium, the number of migrant workers I passed began to dwindle. Most of them were packing up, presumably heading back to their dormitories to rest for the night.

It was probably time for me to do the same.

My legs were starting to ache. Another hour had already passed.

I fancied a spot on an empty field and touched grass. Dry, but cool to the fingers.

Barely ten minutes had passed since I sat down when the sky turned cloudy. It really was time for me to get back home.

Just as I began to gather my things, Beach House spilling into my ears, an unknown figure inches toward me. It was a migrant worker.

He claimed in broken English that he was looking for someone to drink with. But the more I politely declined, the more he urged me to keep him company. He’d already had a few, judging from his breath.

He ended up buying me a can of beer and a chicken pau.

He tells me that he’d come to Singapore in 2008—and after more than a decade here, he’s now 36. He shared that his grandfather had passed recently, after I explained why I was there. Through disjointed back-and-forths, we began to empathise.

As the wind started to pick up, he pointed at a bus park nearby. It used to be a worker’s dormitory, he says, but it was converted into a depot. He shrugged when I asked him why.

Some things are simply beyond our control.

Monumental changes occur in the blink of an eye. People come and go, buildings are built and demolished as the Earth makes another revolution. Grief clings to places, routines, and versions of ourselves that no longer exist.

He awkwardly smiles and tells me he enjoys working in Singapore. He appreciates our stability, our safety, our clean and efficient society—but hates how “unnatural” our food is. For now, though, he’s content.

I ask for his name. Sarabanan.

We exchange numbers so I can pay him back for the beer. We shake hands.

I got going. It hadn’t rained just yet.

Where Do We Go From Here?

As I continued to walk to seek shelter, my stomach grumbled (again). I’m reminded of my love for food, cultivated by my grandmother’s cooking. Slow-cooked 卤肉 (braised pork) and 排骨莲藕汤 (lotus root soup with pork ribs and peanuts), just to name two.

Refusing to check Google Maps for directions, I wander into a random industrial building in search of sustenance. There must be a canteen somewhere on the upper floors.

By some miracle, I stumbled on a canteen serving Indian food. It was empty, as expected, given the time I arrived.

The blinding LED lights illuminating its interior contrast with the darkness blanketing outside. Chairs and tables neatly arranged in an orderly manner. I’m pretty sure this place gets packed during lunchtime.

After settling on a garlic naan, some chana masala on the side, and an iced coffee, I sat down, finally catching my breath.

One of the cooks notices my camera. He gives me a bright smile and a thumbs-up. He asks me where I’m from.

Did I really look out of place here? Maybe it was my camera—or maybe it was because I was sweating hard through my clothes.

He lets me observe as he slices garlic—fast, precise, no wasted motion. I always sucked at it. My grandmother let me try when I was younger, but I never really got the hang of it, no matter how many times she demonstrated her technique. She’d smile as I mangle clove after clove.

Nearby, I spot three large crates filled with plastic bundles. The man explains that it’s catering: 210 packets of food to make up 210 migrant workers’ meals. Each packet stacked neatly, like a small gesture of care in a system that often forgets them.

As for the naan, it was crisp and fresh. It made me feel a little bit more comfortable. Food really is a universal language.

I ask him for directions to the nearest bus stop, which he explains extensively with gestures. He extends his hand for a handshake and gives me a firm pat on the back as I bid him farewell.

Grief in All Shapes and Sizes

I always think I wouldn’t know what to feel or say when I lose someone close. But this walk has taught me that I do know. I just needed the right circumstances for me to do so.

We all will have to face death head-on at some point, but thoughtful living cannot be a substitute for healthy grief. Life goes on, but those thoughts and memories have to be laid to rest at some point.

I start the journey back home; any of the buses here can take me to the nearest MRT station. Life has a way of working things out.

Turning 23 this year was strange. I never wanted lavish dinners or a large, rowdy party. I had always preferred small and humble, yet intimate get-togethers.

This birthday escapade in the middle of an industrial park might be my most intimate one yet: a get-together with memories of my grandmother.

Halfway home, I spontaneously asked my father to meet me at a coffee shop near our house for a kway chap supper. We shared about losing people in our lives—for him, it’s his father and a few friends.

I learn that he, too, takes walks to make sense of it all, often heading to the park in the early hours, when it’s quiet enough to release the thoughts he usually keeps buried.

Looking back, my grandmother always opted to walk wherever she went. She had no need for PMDS or walking sticks—until chemotherapy slowed her down.

I wonder now if her long, unhurried strolls around Woodlands were her own way of carrying grief. Perhaps many of us are just walking off the weight of love that’s gone. With each step forward, we learn how to live with what’s missing.