Top image: Zachary Tang / RICE File Photo

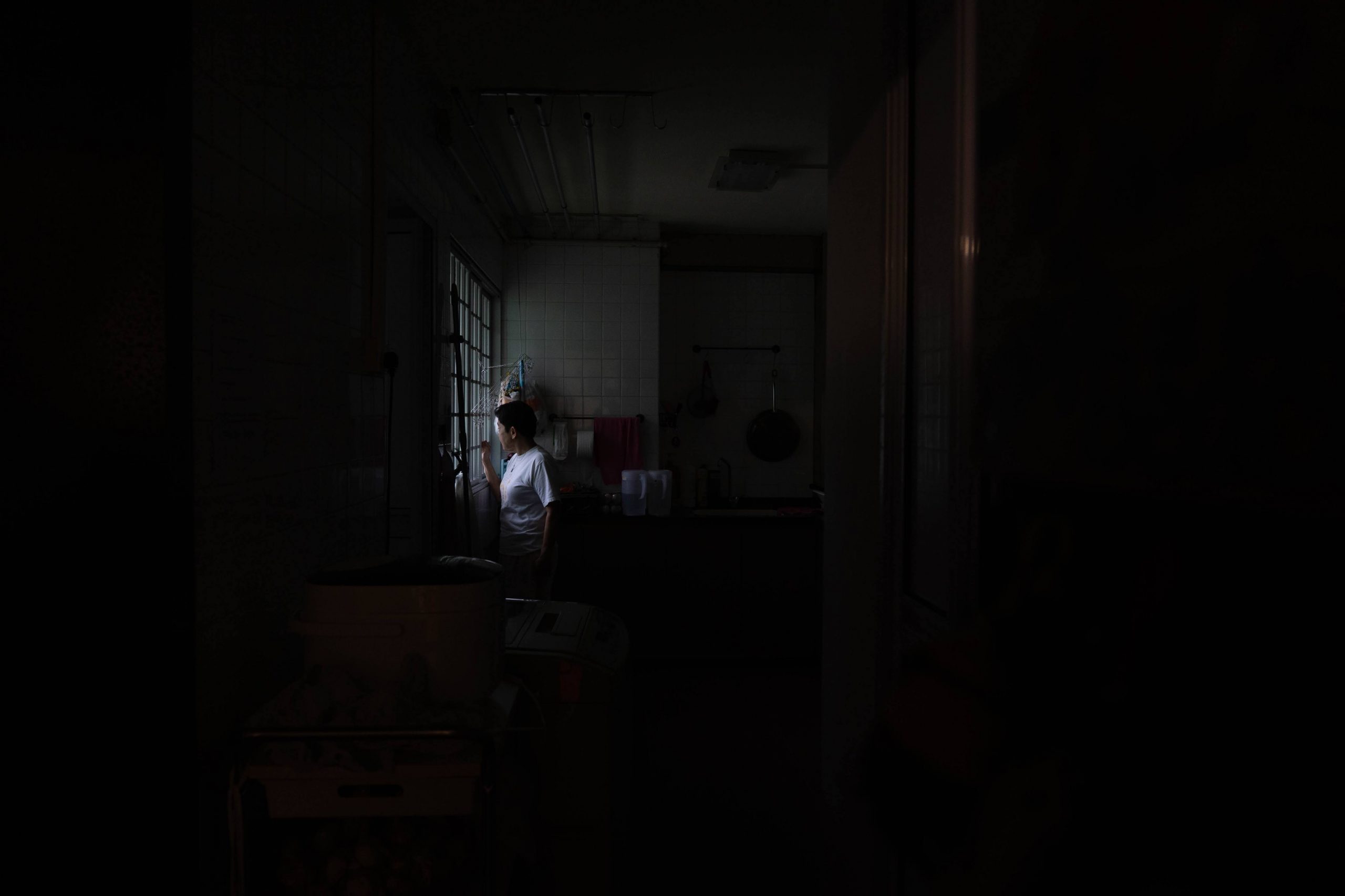

The recent discovery of a father and daughter found dead in their Sengkang flat sparked nationwide conversation about mortality and the lives that go unseen behind closed doors. Yet what truly gripped the public was what came after.

The horror first surfaced when residents living directly below noticed a red-coloured “sticky” and “pungent” fluid seeping from their ceiling. They tried cleaning the unknown liquid by hand with tissue paper, but the stench lingered. When the smell grew stronger, they sensed something was wrong and called the police, leading to the discovery of the bodies above.

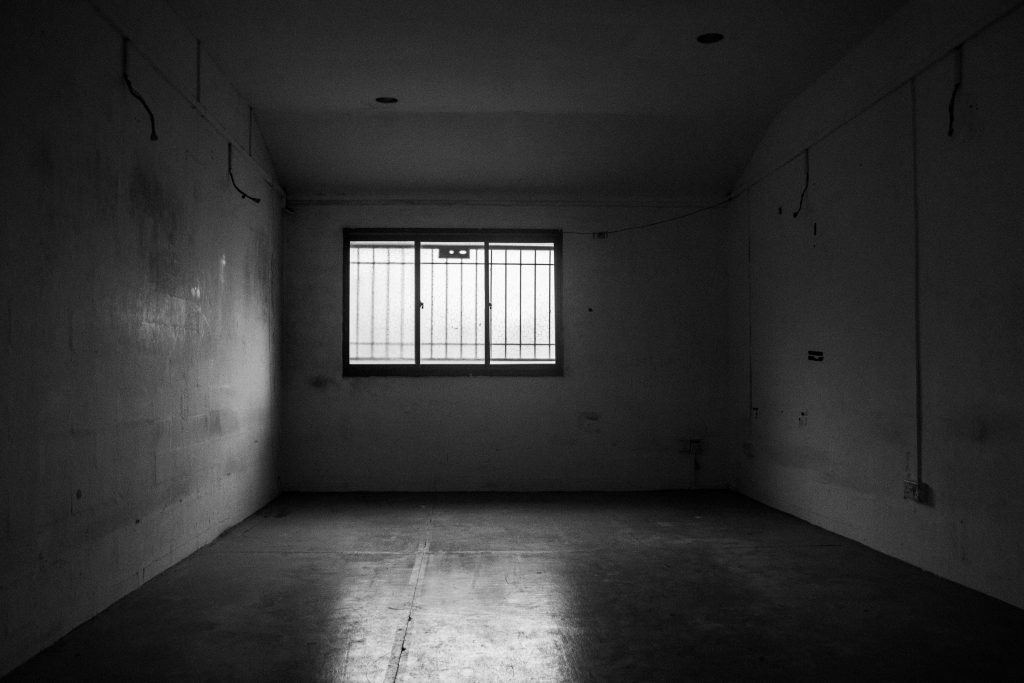

Days after the bodies were removed and the unit professionally cleaned, however, the odour returned. The seepage hasn’t stopped.

While studying forensic science at Nanyang Technological University, I learned how often the residue of death—those invisible traces clinging to walls, floors, and fabrics—becomes the silent witness to what happened within a home.

Advances in DNA and forensic detection have helped convict murderers even when they tried to erase all traces of their crimes. In the 1950s and 1970s, killers like John Christie and Jeffrey MacDonald were ultimately caught despite scrubbing and wallpapering over their flats.

In the case of Richard Crafts (infamously dubbed the ‘Woodchipper Murderer’), blood residue trapped in floor seams helped secure a conviction without a body—a first in forensic history.

The concrete that separates us from our HDB neighbours, it turns out, is not as impermeable as we think.

What We Leave Behind

“When the police discover a body, it’s double-sealed in a body bag and transported by the police hearse to the mortuary,” says James*, a funeral industry veteran with over a decade of experience.

At the mortuary, a pathologist conducts the investigation. The body is usually kept there for up to several weeks, until next of kin are located and the case is closed.

“After that, specialised trauma cleaners are brought in to sanitise the scene,” James explains. What’s left behind isn’t always visible; death leaks into places one wouldn’t expect.

“It’s not just about odour. The fluids released during decomposition can seep deep into concrete and flooring.”

After death, the body undergoes self-digestion and bloating. The bodies in the Sengkang flat were likely in the subsequent liquefaction stage, indicating they had been decaying for at least five days.

In this phase, dissolving tissue releases strong-smelling fluids such as putrescine and cadaverine alongside sulphur compounds and rancid fatty acids. Phenol and ester by-products, too, are known for their sharp, unmistakable odours.

As the body cavity collapses, these volatile molecules escape through natural orifices and wounds.

“If you’ve ever found a dead animal, like a decomposing pet hamster, that’s what ‘decomposition soup’ smells like,” James explains.

“It’s stronger than faeces—choking even if you breathe through your mouth. Imagine seafood left to rot in the sun, only far worse.”

What makes these substances particularly persistent is their chemistry. Acidic compounds etch into paint and tile, while waxy lipids form stubborn films that resist ordinary cleaning agents like bleach or detergent.

Structural materials worsen the problem: wood draws in liquids through capillary action. The same applies to concrete’s countless pores. Grout, the paste used to fill the gaps between tiles, is also notoriously absorbent.

Even after visible stains are removed, bacteria continue digesting what remains, releasing gases and odours that can resurface long after. That’s why the smell of death never truly leaves.

All this to say: our homes are not meant to withstand human decomposition, architecturally or socially speaking. Then again, HDB floor plans don’t account for decay.

The Decay That Sticks Around

Death leaves traces not only in the spaces where it occurs but also on the people who tend to it. Proteins and fatty acids—albumins, keratins, lipids—act as biological adhesives, binding tightly to fibres such as cotton and wool.

Meanwhile, surfactant-like compounds from cell membranes lower surface tension, allowing these fluids to soak deep into fabric. Ammonia and sulphur compounds can also react with dyes, leaving stains that never really come out.

This is why funeral professionals wear fluid-resistant uniforms, made from synthetic materials like polypropylene or PVC-coated fabrics, when handling bodies.

“We ensure that all our employees’ uniforms are deep-cleaned,” says Harmony Tee, 32, funeral director of Harmony Funeral Care and a third-generation undertaker.

For her, the greater tragedy is not decay itself, but isolation.

“Elderly Singaporeans living alone isn’t new,” she says. “But there are definitely more and more of them, with fewer caregivers.”

James echoes this, noting that the trend has been growing steadily. “I haven’t seen a sudden spike, but it has been gradually increasing with Singapore’s rapidly ageing population,” he explains.

In 2024, over 87,000 seniors aged 65+ were living alone—more than double the number from a decade earlier—and this figure is expected to reach around 122,000 by 2030.

When asked whether the homes of decomposing persons share any common traits—such as hoarding, unsanitary or unkempt conditions—James shakes his head.

“The cases I’ve seen are all very different, but one common thread is that the deceased hadn’t been in touch with their families.”

He recalls an elderly man who liked to send ‘good morning’ messages every day.

“When his family, living apart, noticed the daily messages had stopped, they sensed something was amiss.”

Sealing the Cracks

Singapore’s social safety nets are extensive—the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) runs programmes like the Community Befriending Programme and the Silver Generation Office to check on seniors living alone. Financial aid schemes such as ComCare and Silver Support aim to reduce hardship, while grassroots volunteers conduct welfare visits.

Yet, as social workers reluctantly admit, many still slip through the cracks—those who are not considered destitute enough to qualify for aid, yet isolated enough that no one would notice their absence. Others resist outreach, valuing privacy or fearing institutionalisation.

The systems are built to respond, but they are less adept at anticipating silence.

At the time of publishing, authorities have yet to locate the Sengkang pair’s next of kin, underscoring how stark these gaps can be.

Death leaves traces that are both physical and social. When human remains seep into concrete where they were never meant to, they speak of absences no one thought to look for.

The father and daughter were not mere statistics. They were lives quietly lost, revealing the vulnerability of those living alone. James believes that the pair may have been new citizens, without kin in Singapore to check on them.

Ceilings can be repaired, and walls can be repainted. What’s harder is building the kind of closeness that stops people from disappearing unnoticed.