‘After the Vote‘ is a RICE Media series where Singaporeans from all walks of life share their hopes for Singapore—the changes they envision, the values they want to uphold, and the future they want to help shape.

We take a step back to explore the bigger picture: What kind of Singapore are we building beyond the ballot box? Through these conversations, we uncover the aspirations and concerns shaping the nation in the next five years and beyond.

The views in ‘After the Vote’ are those of the interviewees and based on their experiences; they do not reflect the publication’s stance.

All images courtesy of Wong Zhi Wei unless stated otherwise.

When Wong Zhi Wei tells people he’s visually impaired, he’s often met with surprise.

“Most new people I have met—if they have no experience with people with disabilities—tend to see blindness as an ‘all or nothing’ condition,” he tells RICE. “But visual impairment is a wide spectrum. Many of us don’t walk with a cane or have a guide dog.”

For Zhi Wei, who was born blind in his right eye and has 6/60 vision in the left eye, his condition means that he can’t see well from a distance. His phone’s camera, which he uses to zoom in on signs and landmarks, is his biggest visual aid.

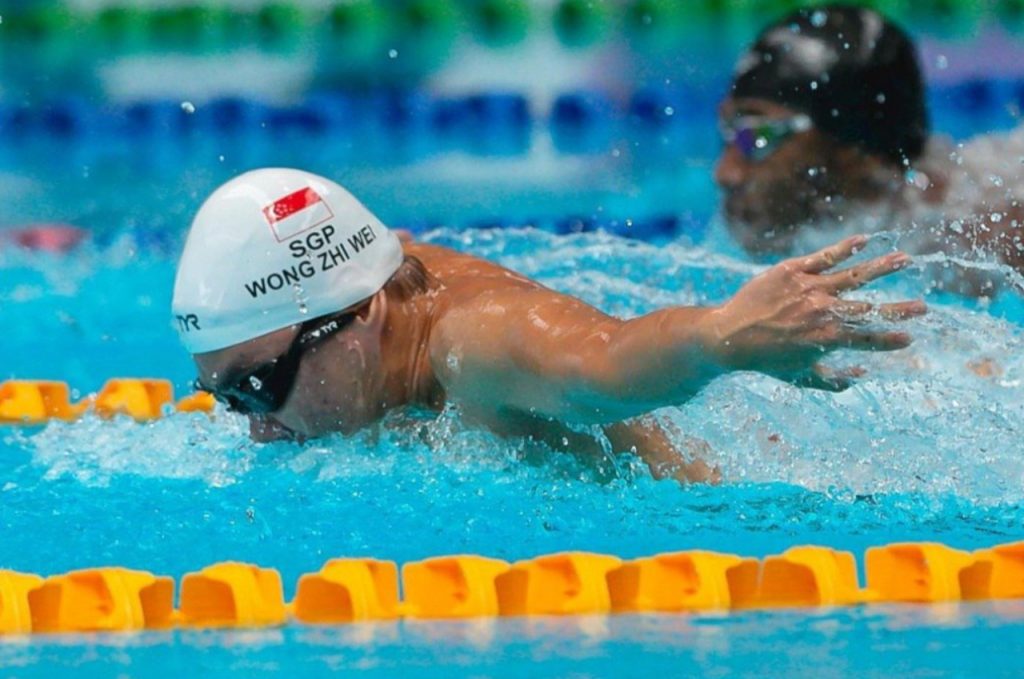

Despite it all, Zhi Wei has accomplished quite a bit at the age of 23. The psychology student at the National University of Singapore is also a national para swimmer.

At the 2017 ASEAN Para Games, he clinched a silver medal in the Men’s 100m freestyle S13 event and a bronze in Men’s 50m freestyle S13 event. Even a Stage 5 chronic kidney disease diagnosis in 2019 and a kidney transplant in 2020 haven’t kept him away from competing.

When asked why being a sportsman is so important to him—even in the face of ongoing health issues—he says it’s given him a space to belong, especially in a school system where few CCAs could accommodate his needs.

It also gave him the tools to face setbacks. “The Sisyphean struggle of trying to break your personal best when you haven’t done so in over three years teaches you a lot about grit and faith in the process.”

RICE is taking a longer-term view towards the Singapore we’re collectively building. And Zhi Wei has plenty to say about how Singapore can give people with invisible disabilities more leeway to be different.

What is one change you hope to see in Singapore by 2030 that would make life meaningfully better for people like you?

I don’t think I can give a complete answer when I ask myself what change I desire for “people like me”. I feel like my experiences don’t exactly qualify me to speak for the challenges and aspirations of my community.

While I am a visually impaired person and a student with a disability, I largely followed the ‘mainstream path’. That is, I went to mainstream primary and secondary school, then JC, and then university.

Of course, I think that there is some level of privilege behind this. My visual impairment is not severe, and I am able to navigate life and academics independently and efficiently.

Nevertheless, I do have experiences that have shaped my perspective on living with a disability here. I think that in Singapore, the pressure to fit in and not stand out leads to less openness on disability and an unwillingness to openly share about it.

In the local context, some of us tend to be hyperaware of how we are perceived, and this hyperawareness could be a result of a society that emphasises conformity.

For example, walking with a blind cane in London is less mentally draining than using one in Singapore, where I try not to stand out. Whenever I use my phone to zoom in and look at road and MRT signs or restaurant menus, I do it discreetly, with the goal of avoiding attention.

Another interesting experience I observed and talked to other visually impaired friends about is the hurdles we undergo when trying to network or socialise.

It is quite difficult for me to recognise faces, especially those of strangers or new people I have just met. I also do not recognise their presence easily. Most of the time, I don’t immediately greet or wave to people until I am near or when they initiate the conversation. I think that this has resulted in some people believing that I am unfriendly or do not want to interact.

It’s understandable since I don’t use a cane, so most of them cannot tell I’m visually impaired.

But it’s still difficult because networking is becoming more and more of an essential skill as we embark on our careers. A visually impaired friend also once told me that she found socialising draining as she felt that she had to overcompensate by being overly friendly so as not to come across as aloof.

Moreover, as someone with an invisible disability, I do not share my condition unless necessary. Perhaps I am a product of survival by assimilation.

I guess, in general, I hope to see a Singapore that puts less pressure on people to assimilate and fit in—a society with more room for people to express and honour the different sides of themselves.

What’s a challenge Singapore must overcome in the next six years to stay a place where people want to live and thrive?

Given its place as a financial and economic hub, I think that Singapore would very likely remain a livable country no matter what.

However, to thrive is a different story.

Singaporeans would need to contend with upholding stability or embracing the risks of change. A common narrative is that Singapore sits on a tight rope of balancing different views, races, religions, backgrounds, social, and cultural beliefs. As such, change comes slowly.

However, there is a fine line between stability and stagnation.

I hope to see a Singapore that is perhaps more accepting and “nonchalant” towards others who do not fit the typical mould of a Singaporean. For example, when someone strays from people’s perceptions of what a disability should look like.

If you could introduce a new national priority for Singapore, what would it be, and why?

As a para-athlete, I would love to see more national attention given to our performances at regional and international competitions—and also a greater effort towards recreational parasports.

When I was 13, my parents introduced me to different parasports (swimming, bowling, sailing) as a way to keep fit and to fish out any kind of potential I had in non-academic domains. I eventually became most competent in swimming. Ever since I was 15, I’ve been part of the Team Singapore para swimming team.

My sport has taught me so much: Humility, gratitude, confidence, and overcoming trauma.

Ernest Hemingway puts it most succinctly: “The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places.”

Without parasports, I don’t think I would have been able to manifest what my teacher called “an indomitable spirit”, which allowed me to finish and do well at the A Levels.

The recent Enabling Masterplan 2030 does indeed include expanding access and opportunities for sports participation for persons with disabilities (PWDs). Through the love and experience of sport, I hope PWDs can be empowered and also build common ground with non-PWDs.

What small shift—policy or mindset—could make a big difference in the daily lives of your community?

Something I’ve been thinking more and more about is how I and perhaps other para-athletes define ourselves.

To become a para-athlete, one has to have a disability first. This is slightly different from able-bodied athletes, who just have to be… athletes.

Perhaps this ontological difference between para-athlete and athlete has led me and other para-athletes to identify as disabled first, athlete second. This could also contribute to the difference in perceptions between able-bodied athletes and para-athletes—the perception that the former represents elite performance while the latter functions as a participatory celebration for ‘unfortunate folk’.

These are just concerns of mine that may or may not resonate with other para-athletes.

Of course, the Singapore Disability Sports Council and the Singapore National Paralympic Council are actively trying to provide a spotlight to para-athletes.

Singapore moves fast. What’s one thing we need to slow down for?

I think many people are too preoccupied with hustling and min-maxing their student and career experiences. I think that there is great value in stopping and smelling the roses.

Practising gratefulness and being happy for what I have or have achieved has helped to ground me beyond the hustle and bustle of daily Singapore life. This is especially so given my experiences as a kidney transplant patient and my continued struggles in sport.

Initially, when I was hit with my kidney failure prognosis, I never would have believed that I could have a meaningful life again. However, after my A Levels and my return to swimming, I gained a second lease of life.

In 2030, what kind of Singapore would you be proud to call home?

A Singapore with many roads to success, where the mould is not set, where one’s value is not determined by extrinsic utility.

If more individuals feel less suffocated and have an easier time expressing hidden sides of themselves, then I would be proud to call Singapore home.