Top image: Unsplash/Cole Keister

The landscape of academic freedom in Singapore is more complex than one might expect, given our reputation as a country of tongue-biters.

ADVERTISEMENT

On the one hand, academia, like journalism, is rife with cautionary tales about the consequences of failing to toe the line. Shortly after I joined RICE, a foreign academic declined to be interviewed for a piece for fear it could jeopardize the renewal of her ‘E’ Pass. Whispers about scholars being denied promotions due to their political views, or being asked to withdraw their findings, abound.

And yet, there are exceptions. At least two prominent Opposition politicians, Dr. Paul Tambyah of the SDP, and Dr. Daniel Goh, a former WP NCMP, have been appointed to senior academic positions in the last few years. (Dr. Goh is now fully retired from politics.)

Meanwhile, the real risk of foreign influence operations, including in the academy, jostles with examples of blatant misuse and the conflation of criticism with ‘disloyalty’.

Earlier this week, in an attempt to shed more light on the issue, a team from AcademiaSG, a collective of local academics, formally launched a new report on academic freedom in Singapore.

The anonymous survey was administered by Cherian George, a co-founder of AcademiaSG and a professor at Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU), and sent to around 2,000 academics in the humanities, social science, business, and law faculties at five local universities earlier this year.

Key findings: not so much ‘whether’ there’s interference, but where, who, and how

On the whole, the survey findings are neither reassuring nor damning. They neither indicate that academic freedom is a myth nor that interference is non-existent. Mainly, it is as frustratingly vague in parts as it is enlightening.

At a minimum, it makes clear that asking whether there is academic freedom in Singapore is less useful than asking what is off-limits, who feels unfree, and in what ways.

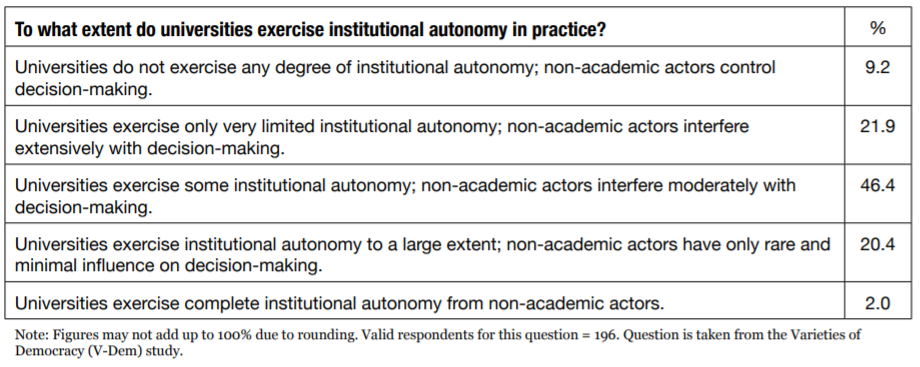

The full document is available online, but some of its key findings include:

1. While the majority of respondents did not feel stifled, a sizeable minority did. This included feeling unable to shape their syllabi or broader research agenda, feeling unable to engage the wider public (e.g. by speaking at events or writing for the media), or being told to withdraw findings for reasons they found unconvincing.

2. Where respondents reported feeling constrained, this was more likely to take the form of self-censorship or institutional signals rather than outright external interference. This included signals from university administrators, advice from peers, and respondents’ own readings of the political situation, in what the authors suggest amounts to a ‘decentralisation of censorship and control’.

3.The distribution of constraint and risk is not random. Foreign academics, as well as those working on ‘politically sensitive’ topics, were more likely to report constraints or inhibitions.

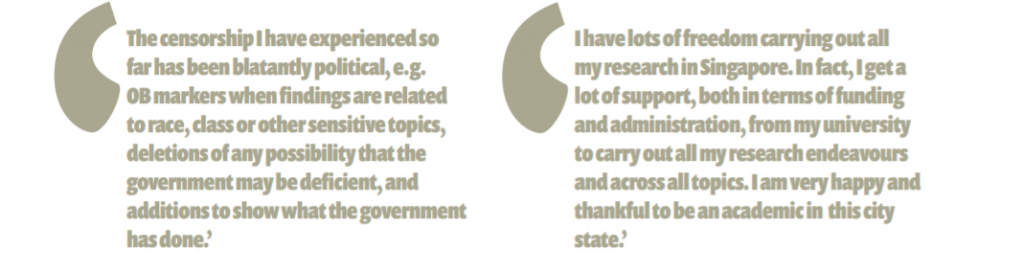

4.Gender, surprisingly, turned out to be a more significant factor than tenure or citizenship status. Female academics consistently reported feeling less able to pursue specific projects, discuss sensitive issues in class, or engage the broader public than their male counterparts.

ADVERTISEMENT

Representation and bias

The survey has its shortcomings, though these, in their own way, relate to the very question it explores: how ‘free’ do academics feel?

First, the 9% response rate automatically invites questions about how representative it is (something the authors acknowledge, though they argue its impact should not be overstated).

At the launch event, panellist Associate Professor Walter Theseira of SUSS noted that apathy might be a possible reason for the low response rate, which he found particularly “concerning”. (He also shared that, ironically, two academics had privately reached out to discourage him from speaking on the panel.)

Linda Lim, a Professor Emerita at the University of Michigan and a co-founder of AcademiaSG, who received similar advice to ‘be careful’, put it this way: “Nobody really knows what it refers to, but you are expected to internalise it.”

When contacted for comment, Dr. Rayner Tan, a researcher at NUS’ Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, also queried the survey’s representativeness, given that only academics from specific faculties were contacted (STEM, for example, was excluded). He also raised bias as a potential issue, though he observed this could go two ways.

“Individuals less affected by issues of academic freedom may feel less motivated to participate, thus biasing the results towards ‘less freedom’, or they could (ironically) be fearful of the repercussions of engaging in such a survey, and therefore bias the results towards ‘more freedom’ than things actually are,” he said.

Whither the OB markers?

Moreover, the survey did not gather data on respondents’ fields of study, which makes it impossible to tell which disciplines are perceived as more risky, or what counts as ‘politically sensitive’.

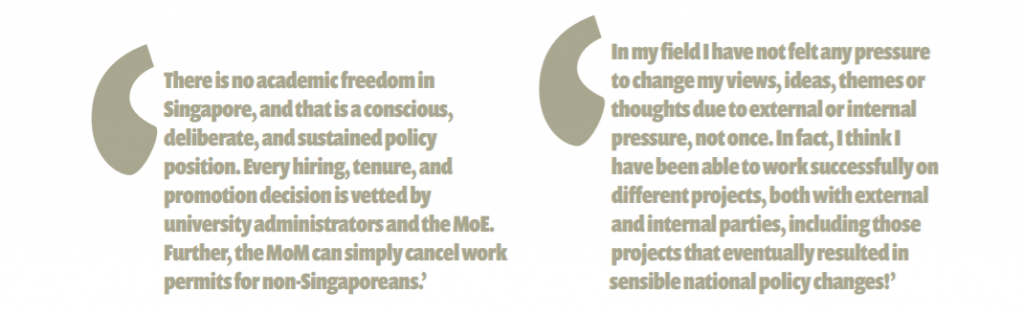

This makes it especially hard to draw conclusions, given the striking polarisation in anecdotal responses:

Going by these, where the OB markers are, like the next GE’s electoral boundaries, is anyone’s guess.

ADVERTISEMENT

The information which would help shed some light is, unfortunately, missing. When does something shade from ‘safe’ into ‘dangerous’?

Several academics I reached out to for this piece shared that they had not personally felt stifled. From their accounts, working on conventionally ‘sensitive’ topics had not affected their careers.

For example, Dr. Tan shared that NUS had been “very supportive” of his work, although it looks into many “sensitive” topics like the health of low-income migrant workers, drug policy, and LGBTQ+ health. “In my experience, as a school, we are driven largely by impact, productivity, and scientific expectation,” he added.

Similarly, Dr. Goh told me he had experienced “no constraints whatsoever”. Despite working on topics like race, religion, and cultural politics, he felt free to contribute to the media and enjoyed career advancement, adding that he had suffered ‘neither censorship nor self-censorship.”

Shortly after reading his message, I spoke on the phone with another academic. They very apologetically declined to comment, citing worries about potential repercussions for their research.

The cost of anonymisation

To be clear, anonymity is a common and important research practice. In an academic community as small as Singapore’s, more safeguards are needed to avoid re-identifying respondents.

Asst. Professor Shannon Ang of NTU, who assisted AcademiaSG with analysing the survey data, gave an example: there are only so many tenured, female professors of sociology locally. A few minutes with Google is all it takes to narrow down a pool of candidates. “The risk of re-identification is very, very high.”

However, the attempt to mitigate respondents’ fears of reprisal also limits the survey’s own insights.

I asked Asst. Professor Ang if it would have been possible to ask for respondents’ fields of study anyway, and simply redact the data from the dataset before publishing it online. He explained that there were concerns this would be insufficient to assuage people’s fears. Even with anonymity, the team worried that potential respondents might still have been scared off by the extent of the info-gathering.

Why do female academics feel less free?

Over email, Professor Linda Lim, one of the AcademiaSG co-founders, offered some hypotheses regarding the findings on gender.

While noting that further research was needed, she suggested that this could reflect broader societal issues with gender norms and representation.

“[Women] are underrepresented particularly in university leadership hierarchies, for example, just as ethnic minorities are, so are more likely to feel powerless or fearful of authority,” she said, adding that gender stereotypes might make women more reluctant to express contrarian views for fear of appearing ‘aggressive’ to male colleagues and superiors.

However, she noted that it was a “pity” that the survey was not able to shed more light on this due to the extent of anonymisation.

“We can’t tell if women tend to be clustered in fields or work on topics which are likely to be more ‘politically sensitive’,” she said.

Are academics ‘freer’ overseas?

It’s also notable that the project was administered by a Singaporean academic at an overseas university. While approval was sought and obtained from HKBU, one can’t help but wonder if a local institution would have green-lit such a project.

In fairness, foreign universities are hardly bastions of liberty. Many are mired in their own battles over censorship and cancellation.

It’s also worth asking whether the academy practices its own form of gatekeeping by shunning certain areas of thought or scholars of particular backgrounds while privileging others. In their own ways, market forces, university rankings, and promotion and tenure processes exert influence on academic choices.

Nonetheless, while many scholars in the local academy produce critical, thought-provoking work, it’s impossible to ignore that some of the most politically sensitive ‘Singapore scholarship’ has come from academics based abroad, such as the work of Netina Tan or Lily Zubaidah Rahim.

So what?

Academic freedom has implications for Singapore society as a whole, not merely scholars themselves. The job of an academic, after all, is to interrogate the status quo; to expand what we know, seek truth, and sometimes, speak truth to power, even when this might be unpalatable or unorthodox.

It’s not even necessary to get bound up in arguments about liberties or freedom of speech. One need only look as far as the climate crisis or wealth inequality to see the need for diverse, independent scholarship.

In the meantime, one can only marvel at the devastating irony: that a survey on academic freedom felt the need to tread so carefully, with findings that raise as many questions as they answer.

If you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram. If you have a lead for a story, feedback on our work, or just want to say hi, you can also email us at community@ricemedia.co.