I was nine when he stumbled into me.

The periphery of the incident has always been hazy—did it happen on the train, or outside the library? Was I in uniform or some demented shirt-and-shorts combination my mum chose?

But I will always remember the jittery man, his hands a little too rough with the way he groped outwards, as though needing to hold on to something. I don’t think he grabbed me. I think he wanted to, but stopped just short of scaring the shit out of this tiny child.

Like any well-behaved mummy’s boy, I’d learned to not talk to strangers. So after saying excuse me, I teetered away from him. I stole a glance back, and while as a child I didn’t understand this was a man suffering from mental illness, I knew I felt upset.

Did I feel upset at him? For him? At myself for not doing anything? Who knows. I just knew something was off.

Mental illness is also often invisible.

My experience with mental illness is mostly benign. I have social anxiety—which at its worst cost me a job interview and me sitting on my arse for three hours paralysed in my own thoughts. It’s not something people expect, but neither are they surprised.

It’s a pesky quality of life issue these days, mostly impacting my correspondence with strangers. To cope, I write all my messages separately—yes even WhatsApp messages—and scrutinise and double check them thoroughly. I sometimes even send them to others to vet before copy-pasting the message to be sent. In a job where I have to constantly reach out to people, the amount of time I have to spend dealing with this can be quite frustrating!

This doubly applies to phone calls. Once before making a dental appointment, I would write down exactly what I wanted to say, complete with all the possible scenarios the conversation could take.

It took me twenty minutes to prepare for a one minute call.

Their stories have far more gravity than mine.

Writer Maryam Noorhimli—who crafted the text and interviewed the actors with fellow writer Harris Albar—shares one story which struck her. An interviewed actor had shared that they had kept a suicide note in their bag for a week, even bringing it to work. All the while people remained unaware of the note, which was detailed enough it couldn’t have been a spur of the moment decision. Maryam says that having worked with the actor before, she always saw them as an exuberant person. Definitely not someone leaning over the railing of suicidal ideation.

Now, it’s far more common to suddenly find an acquaintance you’d never expect to end up in IMH, or worse. Sure, there are still ‘jittery men’ roaming the street, but the vast majority of people struggling with mental health walk among you and I, unseen and unheard. We often don’t find out until it’s too late.

“It could be anybody,” Karen tells me, sighing into her knees.

Here, an interesting angle for interrogation opens up. The archetype of the ‘brilliant but tortured artist’ is as enduring as a piece of Van Gogh. It begs the ouroboric question: does mental illness find its way into the arts, or does the arts cultivate mental illness?

Obviously, the cast doesn’t have an answer for me, but there are a few hypotheses.

Masturah suggests that perhaps the pressure put on artistic geniuses by singling them out might cause them to fall that much harder. Matin shares how he struggled to compartmentalize between the different ‘bodies’ that actors inhabit, allowing various roles and his personal life to seep into one another. The vulnerable, emotional work that actors subject themselves to is an occupational hazard that might escalate mental illness if left unchecked.

Haresh posits that the archetype comes from artists’ misery being sensationalised. Happy, wholesome artists don’t make headlines, and these stories don’t get told. We have to be careful in peddling such narratives that can be destructive to an entire industry.

But the industry takes its toll on its professionals as well.

It’s no secret that people don’t go into the arts to get rich. There’s no money in creative industries—and any that’s left go to very few. In the mind of the practical Singaporean, being in the arts is akin to playing Russian Roulette with your 5Cs.

This leads to another whole host of problems such as not having a strong support system from friends and family. There are countless stories of disapproving parents who would rather their artistic child go into finance or some other soul sucking career.

Writers Harris and Maryam have their own observations as well. Harris states that creative industries don’t have the luxury of time. Cast and crew barrel on from production to production, striving for quick and efficient work in the precious few months of rehearsals they have before it’s showtime. Caring for one’s mental health is often cast aside because it hinders one’s work, and it’s only a death spiral from there.

Maryam notes how the industry is brutal in its demands—and unforgiving in its rejections. With one’s art and craft often tied deeply with one’s sense of self, multiple rejections can feel devastating. As though a repudiation of one’s entire being.

Mental illness is becoming increasingly common today, regardless of industry, and especially in our youth. It doesn’t take a psychologist like Oliver James to draw a correlation between increasing mental distress and the structure of neoliberal capitalism present in most first world countries today.

Cultural theorist Mark Fisher wants to reframe the way mental illness is discussed by focusing on its structural aspects. In his book Capitalist Realism, he claims that mental illness is currently seen as a personal failing. It’s on the onus of the individual to manage and self-medicate.

And so Fisher rallies us to politicise mental illness. The pervasiveness of individualism, hyper-competitive industries, maintaining self-worth through consumerism—these are anxieties that can’t be privatised. Societal issues require societal solutions, if not they lead to societal problems.

Matin’s character, Zac, says as much in a monologue: people are angry, tired, scared, and fighting all the time. Everyone’s going crazy, lacking proper human connections and an outlet to release their frustrations. That’s how it is on this bitch of an earth.

Expecting a drastic overhaul of our economic system is a pipe dream. Even the most optimistic radicals can see that. So if we’re all at our wits end and the system isn’t going to change, we should at least be granted the tools to cope with how fucked everything is, right?

But we can’t even do that.

I know that it’s partially in jest when Zac suggests that the solution is for the government to appoint a therapist for every person. But I wish such a measure would be feasible. One of the largest barriers to treating mental illness is how expensive it is. Even coming from a well-to-do family, I still balked at the bill after my first session. Whipping out a calculator, I realised there’s no sustainable way for the average Singaporean to have long term mental health care.

Weekly, hour-long sessions can reach close to a thousand dollars a month. And we’re not even factoring in the medication.

But talking about these solutions feels so far away. Karen pops my bubble by admitting that in her experience, mental health is far beneath many others’ priorities.

“Even beneath STDs,” she jokes, before strong-arming me to place a disclaimer that these aren’t actual statistics.

“If you say you have HIV/AIDS, you elicit sympathy which you don’t get when you reveal your having mental illness. Many people’s reactions—including mine, being born in 1967—would be to ask why?”

The continuation of the accusatory ‘why’ seems to materialize before my eyes. Suck it up and stop being such a fragile snowflake! Don’t you know everyone’s having a hard time too?

But how has it become acceptable for an entire generation to be so stressed out that we struggle to maintain our mental health? Since when did we start to see suffering as a personal weakness to be corrected and not the failings of a system that was supposed to support us?

Ignoring mental illness because of its stigma does no one any good. Its invisibility is in no small part due to the self-censorship of people to suppress their illness. Harris notes that many actors fear that having a mental health condition affects the work you get in the industry, and again, this is applicable to society at large. Pretending that mental illness doesn’t exist only exacerbates the problem until it can no longer be hidden.

We have to start talking about mental illness, and what we can do about it.

Haresh says that much more attention is required inside the industry, and acknowledges how complex the situation can be. “Different phases of rehearsal require different kinds of investment. Just how do you care? There’s no hard and fast rule because different actors have different needs.”

But undergirding any kind of care would be communication: “A lot of talk needs to happen to work something out. And everyone needs to be involved—from the director to the stagehands.”

“Care has to be tailored and negotiable between one company to another, one show to another,” Karen adds on. “Obviously a show like Broadway Beng is very different from what we’re doing here.”

Andre talks about mental health days as a way to cope. “There would be days back in school when someone would just not show up for a rehearsal and we’d ask where this guy is. The reply would be that he’s just not feeling well. He’s mentally not in the right space and he can’t come down today.”

“Maybe that’s the kind of understanding we need now,” Karen replies. “Maybe mental illness is so prevalent these days, it’s like the flu and you just need a few days off.”

Beyond the industry, I asked the actors what they hope the general public can take away from Acting Mad.

Masturah shares her initial anxieties regarding mental illness.

“I’m very fortunate to not experience mental illness myself, but I do know of many friends who struggle with their mental health. And I’m always so worried that I might do or say something bad that might be triggering.”

“But you just have to talk about it,” she continues. “You have to be comfortable to have these conversations and asking about what your friend needs. And then you can learn. It’s just the same as if your friend’s going through anything—you need to be able to address the problem, and ask them how can I help?”

Matin reinforces Masturah by stating that his greatest hope is for the audience to acknowledge mental illness and start talking about it.

“If we can do that,” he says with a smile, “Then I would say we have succeeded.”

“Depression manifests in many forms,” Andre says, echoing how mental illness can feel inscrutable and undefinable. “Embracing diversity and our differences in how we deal with it might be what’s important when helping others.”

“Personally, I’m interested in the idea of theatre as a cave,” he tells me. “When you are in the space with your actors and with your audience, they become your community for the moment. People may struggle with mental illness, but the work is what pushes them forward. It becomes their outlet for managing mental health.”

Finally, Karen recounts an anecdote from many years ago when she did an interview on depression.

“A relative called me up and told me: at least you don’t have bipolar. The insinuation was ‘at least you’re not really crazy’—you know that kind of idea? As if there is a difference. It made me realise that I—and many others—really don’t know anything about mental illness and the people who suffer from it.”

“You just have to be kind,” she says. “You really don’t know what someone else is going through.”

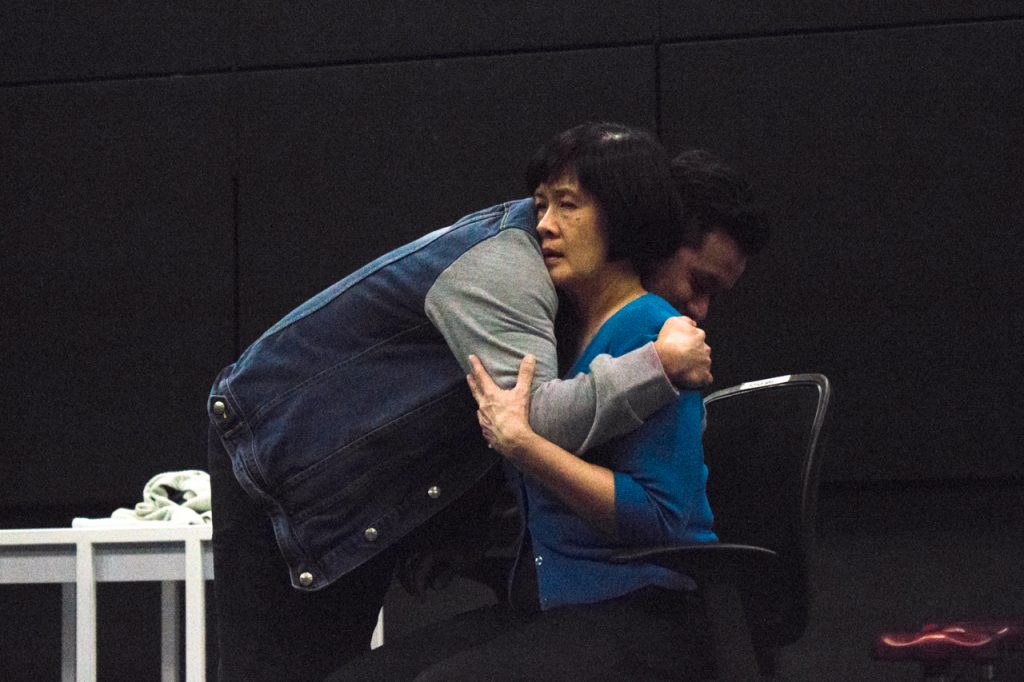

I want you to go watch this production, so I won’t spoil what this entails. But I accepted it. The actors reacted with surprise, anxiety, and relief all at once, their train of emotions distilled into tiny gestures. Eyes widening a fraction, a sharp intake of air, a twitch in their smiles.

As they would later tell me, it had been the first time someone accepted, because no one had been there to respond before. The magic of the theatre comes from the two-way between actor and audience. Within a rehearsal space, you don’t get that.

Likewise, the magic of society comes from the interactions between people. Relationships are a dance of give and take in the dark. It’s daunting to commit when you feel like you have two left feet, when you don’t really know who your partner is. But you just have to reach out.

Hell is other people, sure. But so is heaven.

I held Masturah’s hand, and I understood why the jittery man wanted to hold mine, all those years ago.

Do you want to talk about mental illness? Reach out—and hold on—to us at community@ricemedia.co.