Can people with vision impairment or hearing loss enjoy theatre? Can those with mental disabilities even understand it?

As small-minded as these questions might be, they lurked ominously at the back of my mind when I attended an open rehearsal for Not In My Lifetime?, Singapore’s latest inclusive arts theatre production.

To get some answers, I spoke to Alvan and Beng Tian, the playwright and director for this new play.

It was in 2006 that director Tan Beng Tian first met Alvan Yap.

“At the time, Alvan was teaching at the Singapore School for the Deaf,” says Beng Tian. Alvan is himself deaf.

Then, in 2017, Beng Tian joined Project Tandem (where Alvan was freelancing as a verbatim script editor), a local initiative that pairs budding disabled artists with experienced mentors to guide them in the craft.

“I reconnected with Alvan – I read his blog, his other writing, and I realised that he’s actually quite a prolific writer,” says Beng Tian, “So when I wanted to do inclusive theatre, I naturally asked him to write my script.”

“I’ve never written a play,” responded Alvan, at the time. “What should I write about?”

“Write from your heart,” Beng Tian replied.

“What do you want to write about?”

The answer to that question is found in Not In My Lifetime, the latest production from puppet theatre company The Finger Players. The play revolves around two SPED (Or SPecial EDucation) teachers, capturing their day-to-day struggles and the larger feeling of frustration held by many in the field.

For The Finger Players, it is their first foray into the Inclusive Arts; an approach to theatre that seeks to make the performance accessible to members of various disabled communities, from those with sensory differences to people with autism.

But what was the impetus for putting up such a specialised production?

“During the project, I got to know some PWDs. People who were blind, people with autism, cerebral palsy; I started to be more aware. When we wanted to meet, there were many places that were not conducive to them.” This included the theatre.

“It made me feel … not pity, but frustration. I am so privileged, my friends are not, how can this be?”

That’s what spawned the idea for this production.

“We want a show that many different people can enjoy. A conversation … that can spark people to make a change.”

At present, Beng Tian feels that “Singaporeans are not against Persons with Disabilities, just not aware [of them].” She says that it is important to “consider them in [our] decision making.”

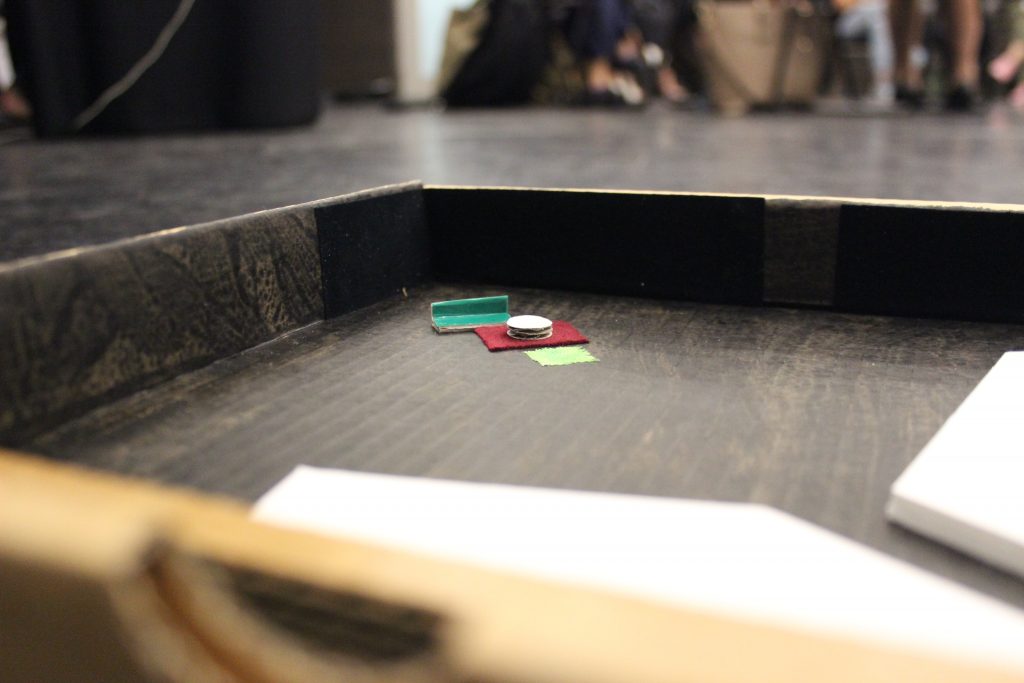

The play contains several elements that make it more accessible to those from the PWD community. For audience members who are vision impaired, a pre-show ‘Touch Tour’ allows them to physically feel around a small model of the set.

Sighted audience members will be offered blindfolds during this segment; they can choose to participate in the experience in a manner similar to that of their blind counterparts.

For the deaf, closed captioning is provided during the play, and the preceding Touch Tour is accompanied by sign language interpretation.

This description is done in the form of a projection against a plain wall next to the performance space; in this way, the deaf can simultaneously watch the action and read the captioning to more fully understand the performance.

Act Three

Making an inclusive performance is not without its challenges, most obviously of which is budgeting.

“People are basically working half pro-bono,” explains Beng Tian, “Doubling or tripling their job scope. We hired Nix and Evelyn as actors, but they are also doing sign language interpreting.”

A tight budget also means the play’s puppets and props are assembled from household items that the team scraped together.

“There is a real lack of expertise in inclusive theatre here,” Alvan adds, “It is something new in local theatre, so there is a steep learning curve.”

“There was one rehearsal,” says Beng Tian, “When one of our actresses was sitting next to a puppet. And on inside this puppet’s ‘head’, which is actually a dustpan, was a magazine. While rehearsing, the actress picked up the magazine and start reading! We all thought it was very funny, and we were going to [include] it, but then we realised that this joke cannot be told to a blind audience.”

As it was a visual gag, that joke simply would not have been be funny to the blind, even in an audio description.

“What, are we going to have the puppet say: Mummy, why are you taking the magazine out of my head?” jokes Beng Tian.

However, this does not mean that the players are restricted in their performance.

“We are not forgoing [anything], we are finding other fun parts that can be shared, together, by both the blind and seeing audience.”

“So why do you listen to football commentary?” Alvan shoots back.

“I mean, you can watch football, but even if you don’t, you will still enjoy the commentary right? Truth is, a lot of the enjoyment [of arts] occurs in our imagination. We underestimate the extent to which people with disabilities can enjoy it too.”

I concede that this is true. After all, it’s the football announcer’s voice that really gets my heart thumping, even if I’m not too focused on the game.

“Why do deaf people go to concerts? They cannot hear well, or cannot hear at all, right? But they can feel, they can feel the vibration inside.”

Similarly, the theatre experience of those with sensory differences is “different, but not inferior” from that of their non-disabled counterparts. They can still enjoy the show.

“Also, it’s not just about sensory experience,” adds Alvan, “Theatre is all-rounded: it’s the feeling, the energy of the audience, something you can only get in a live performance. It’s about enjoying the company.”

To make the play accessible to them, seven of the fourteen ticketed performances will be ‘relaxed performances’.

“Relaxed performances mean that anyone will be allowed to move in and out of the theatre, go to the toilet, and so on,” says Beng Tian.

I ask why this is necessary.

“What’s expected from a theatre experience? Absolute silence. We’re annoyed by other sounds.”

In a typical theatre, people who are unable to stop themselves from making such sounds, for example those with a vocalised tic, will be asked to leave.

“After all,” she jokes, “If we can focus so intensely on smartphones, we should be able to use this ability to concentrate on a show together with members of the PWD community.”

Beng Tian explains that many of them may want to come to the theatre, but they are unable to do so. Due to their involuntary behaviour, they are unwelcome in such a stifling environment. With the relaxed performance, the players hope they will feel welcome to attend.

However, this has raised other potential challenges. During the feedback session, Mrs Jennifer Chee, a senior social worker at MINDS Woodlands Garden School, raised a salient point:

“Children with Autism may be oversensitive to noise and light. They may not be able to stand the loud noise in one of the scenes, and may try to cope with the sensory overload by covering their ears, or react differently.”

“They are capable to enjoy and understand the play.” Jennifer corrected me.

“Arts is a medium [for] which you need no words. Just a sound, or a look, and you can feel it. They (PWDs) have the same emotions as all of us.” They may have difficulties recognising and expressing emotions. However, everyday interactions, and enabling them to attend such events, will help them to learn more about feelings and improve their ability to express and respond to emotions.

She adds, “In fact, I have watched a drama performance put up by students with special needs. They managed to perform a 3-act play!”

This different treatment is the key issue raised in the play.

“Right now, who is responsible for Special Education?” Alvan quizzed me. I confessed my ignorance.

“SPED schools are run by various Voluntary Welfare Organizations (VWOs), not MOE. In all other developed countries … the education ministry is in charge. Here, education of special needs students—it’s not education. It’s just a social welfare issue.”

“The play is a commentary on why we have separate education for those with and without disabilities, and the disparity between the two systems.”

“In the arts sphere,” says Alvan, “We are more open minded. In the mainstream world, it may not be worth serving a minority community, may not be cost effective. These questions exist in the arts also, but we are more willing to do it here. We are not solely about profits, this is where we can make a breakthrough.”

A breakthrough in what, exactly?

“More than ten years ago, solo wheelchair users were rare. If they were outside, someone was pushing them; they were not independent. This is because back then most places were not accessible to them. Now, we don’t give them a second glance—that’s what is meant by normalised. We want nobody to be surprised by PWDs.”

In pondering this contradictory-seeming aim, I can’t help but draw a parallel to the deliberate de-ghettoisation and integration of racial minorities into the Singaporean Chinese community through the government’s public housing policies. Through a policy singling out minorities, conditions were created that normalised their presence.

If it can be done for one minority group, why can’t it be done for all? Or perhaps it’s just because PWD-minorities can’t riot quite as effectively? Though the sight of a motorised-wheelchair fleet rolling calmly through the streets hurling molotov cocktails would doubtless make any riot policeman defile his trousers.

After speaking to the playwright/director pair, and watching the tear-jerking performance, the thing that stuck with me the most was one of Alvan’s comments: “different, but not inferior”.

As we conduct our daily lives, we feel perhaps a slight surprise; a twinge of pity, for those who appear disabled in some way, yet dare to face the public. Sometimes we briefly wonder, somewhat involuntarily, how sad and dejected their lives must be.

What we fail to realise is that their experience of life, just as their experience of theatre, is just as how Alvan put it: Different, but Not Inferior.

In other words, Different, but Equal.

More details can be found on the Finger Player’s Facebook page. Book soon, because tickets are selling fast.

Have something to say about the story? Write in to community@ricemedia.co.