Top image credit: Cheryl Tang.

It all started when my editor, always on the lookout for new ways to challenge his writers, arrowed me to attend a talk called A Librarian’s World: In Defence of Self-Help.

Editor: We should send a cynic to attend this. Sophie?

Me: I’m not even the most cynical person in the office. Ask PJ or Grace.

Editor: Yeah, but that’s precisely it. You’re an idealist who also thinks self-help books are crap. This is the best sort of inconsistency. Therefore, you should go.

Me: Can I get out of writing another piece if I do?

Negotiating skills aside, he has a point. I’m an idealist about a lot of things—human goodness, civic engagement, even writing for a living in the Internet age—but not self-help books. To me, those have always been the literary equivalent of juice cleanses: facile, feel-good nonsense for the desperate.

Which is why, when I trudge to the Central Public Library (the talk is organised by the National Library Board) one Saturday afternoon, muttering about ‘abuse of executive power’, I find myself grudgingly intrigued by the presenter’s thesis.

Sparknotes version: Self-help books have been unfairly demonised and should be allowed to prove they’re not just a waste of time.

Longreads version: If you think self-help books are dumb, you’re probably thinking of the ‘old’ version of the genre. Following an image overhaul to rival anything on Extreme Makeover, Self-Help 2.0—aka ‘personal development’ or ‘self-enrichment’—now covers everything from ‘macro’ life advice (how to be more resilient/happier/successful) to ‘micro’ issue-based advice (how to unplug from your phone, Konmari your stuff, and so on).

Moreover, self-help books today are more realistic in their promises. Many are backed up by extensive research and data, rather than being mostly conjecture. Some of the bestsellers are written by celebrity academics with Ivy League credentials, à la Angela Duckworth or Susan Cain.

In other words, self-help is no longer for those too stupid to recognise snake oil when they see it. It’s for smart, self-aware people just trying their best to be better.

Semi-convinced, I set out to borrow a few books on mindfulness.

Mindfulness, if book sales are anything to go by, is the route to the good (calm, stable, well-adjusted) life, endorsed by everyone from CEOs to monks. Despite this, I’ve never been able to get my head around the concept, which seems too fluffy and commodified to be truly helpful. Yet as a constitutionally anxious over-thinker with a PhD in imposter syndrome, I’m probably exactly the sort of person who could use it.

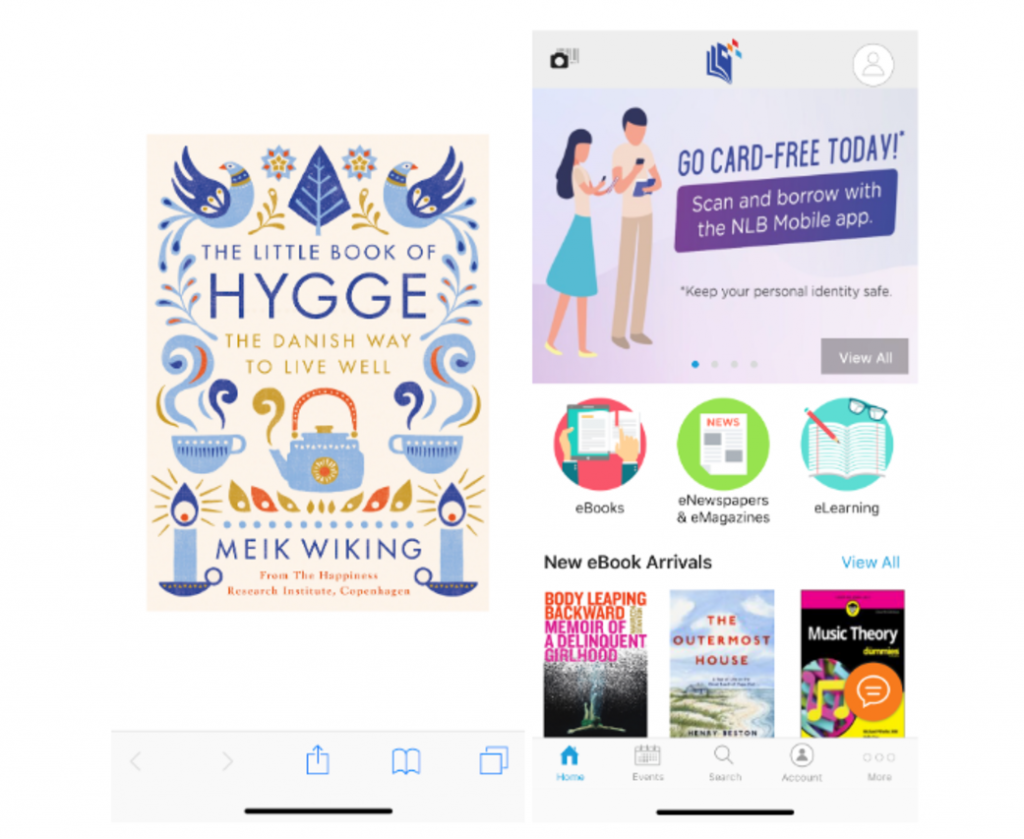

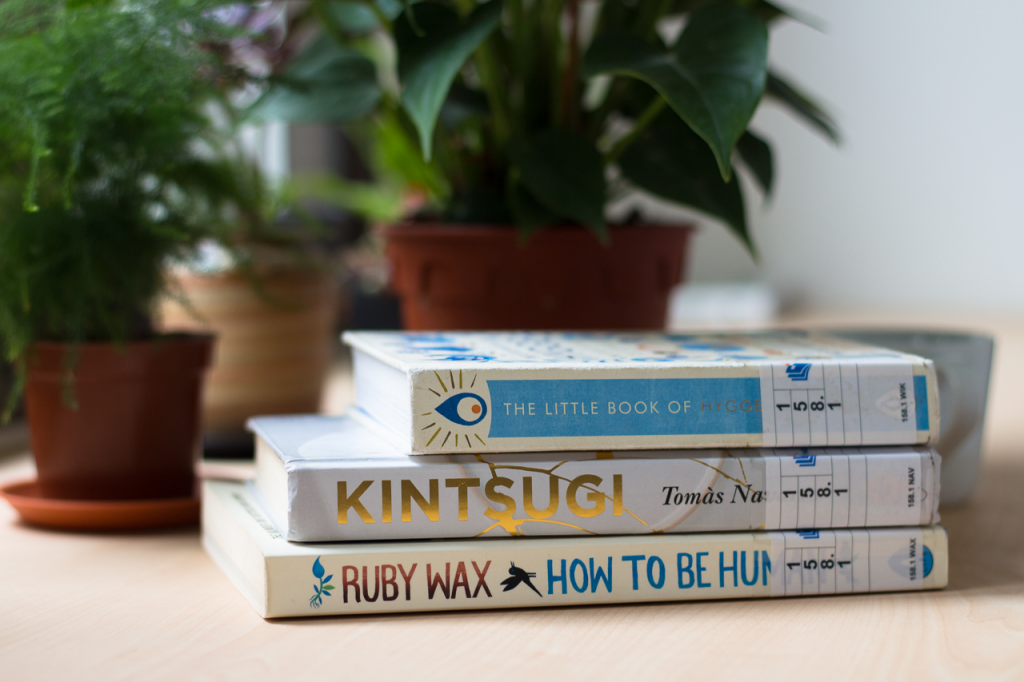

I emerge from the library with three titles: The Little Book of Hygge: The Danish Way to Live Well by Meik Wiking, Kintsugi by Tomas Navarro, and How To Be Human by Ruby Wax (plus three unrelated books, just because).

All are loosely connected to mindfulness and learning how to be present. Hygge provides practical suggestions for how to ‘live well’, “taking pleasure from the presence of soothing things”. Kintsugi’s blurb tells you to “embrace your imperfections, overcome doubt and shame, and find happiness”. Meanwhile, How To Be Human takes a cognitive approach to mindfulness, explaining (in layman’s terms) what goes on in our brains when we think and feel.

Happiness Looks Like a Pinterest Moodboard

According to the Danes, happiness is wearing sweaters, drinking hot chocolate, snuggling by the fire, going mushroom foraging, and other activities generally unsuited to swamplike humidity and 32-degree heat.

Hygge (pronounced ‘hoo-gah’) is hard to pin down, but can be loosely defined as ‘cosiness’. If it’s rustic, charming, and makes you feel warm and snuggly, like “running your fingers through the hairs of the skin of a reindeer,” it’s hygge. Wiking, the CEO of the Happiness Research Institute in Denmark, believes this art of appreciating the little things is why the Danes rank amongst the happiest people in the world.

And according to him, it can be replicated. So despite being short, reindeer-less, and deeply sceptical, I spend a week doing my best impersonation of a Dane.

I borrow an oversized cashmere sweater and move into the quietest room in the office, turning the AC up in an attempt to mimic the Scandinavian winter (and stop myself dying of heatstroke, if not from guilt about my carbon footprint). I light a scented candle, drink more black coffee than usual, play lots of Billie Holiday, eat my weight in biscuits, and procrastinate by staring absentmindedly at the office plants.

It’s … nice, I’ll give it that. My little pseudo-Nordic workspace becomes an oasis amidst the insanity of Rice HQ. More than one colleague walks past and exclaims how wholesome my spot is, compared to the surrounding cesspit of angst.

But despite the much-needed serenity, I’m not fully convinced.

The verdict:

Hygge might be a state of mind for the Danes, but for us here in Singapore, it will never be more than an aesthetic to buy into. It’s also undercut by Wiking’s observation (tucked away towards the back of the book) that the Danes also have an excellent social support system. Mulled wine and long walks in the forest are great, but so are low-income inequality, good work-life balance, and strong social relationships.

This said, it’s true that small, superficial lifestyle choices can make you feel better. Succulents and sweaters might be pretentious, but are no more deserving of scorn than my usual choice of exercise classes or skincare products. Arguably, rather than being self-help, hygge is something closer to self-care: a light-hearted, frequently consumerist coping strategy.

Embrace Imperfections, Including Imperfect Books

Confession time: I was drawn to Kintsugi mainly because 1) its cover is pretty, and 2) its recollection of one of my favourite quotes: “Break a vase, and the love that reassembles the fragments is stronger than that love which took its symmetry for granted when it was whole.”

I want Kintsugi to impress me. The concept, inspired by the ancient Japanese art of golden joinery, seems both poetic and wise: that the cracks in our selves exist to be filled by acceptance, humility, and growth. I start reading, cautiously optimistic.

The book is divided into three parts, the first two being a more general discussion of emotional resilience, and the last being context-specific (e.g. developing this in the wake of a breakup or the death of a loved one). Although some parts hit home—I feel personally attacked when he talks about going to unnecessary (read: counterproductive) lengths to prove a point to yourself—other points are hilariously banal:

- “Incorporate emotions into your life.”

- “Manage adversity.”

- “It’s always more encouraging to predict an optimistic future.”

- “Identify and manage negative delusional thoughts.”

- “Analyse what happened to you.”

To give Navarro some credit, none of what he says is bad advice per se. I don’t actually disagree with the content of the book; while sometimes condescending (“You’re broken and we need to repair you”), it’s mostly kind and empathetic.

It takes me several tries to approach the book with the same self-awareness it preaches. Navarro’s advice is too broad for me to find helpful, but that’s not to say it wouldn’t work for someone else. As he puts it, “Life is the way it is, but depending on where you focus your attention, you will be able to see some things instead of others.”

The verdict:

Kintsugi wasn’t my cup of tea, but its imperfections might be just right for another kind of reader.

Self-help, after all, is an inherently subjective genre. Anyone who gives it a shot will be at different stages of looking for answers (or identifying their problems), and finding a book that really speaks to you can be as much a matter of trial-and-error as finding a therapist you click with.

How To Be Human? Start By Breathing, Apparently

The cover of How To Be Human sports the following endorsement from Russell Brand: “Beautifully fused neurology and spirituality … all other books will become defunct.”

I wouldn’t normally trust Russell Brand when it comes to making good life choices, but to my surprise, How To Be Human is not a bad read. I might even go so far as to say it was … helpful.

The premise of the book is unusual. Wax, a comedian, actress, and mental health campaigner with a Master’s in cognitive therapy, uses conversations with a neuroscientist and a monk as a vehicle to explore mindfulness.

Unlike Hygge and Kintsugi, however, it does not explicitly promise to make life better.

I decide to try out some of her practical tips for practising mindfulness, starting with the art of body awareness. Lying awake at 2:00am, trying to quell the deadline panic monster eating my chest, I think of Wax’s advice: Focus on your breathing. Don’t worry if your thoughts wander, just try and bring your attention back to one body part. I try breathing in and out over 6 counts, focusing on the tip of my nose, and slowly feel my limbs relax.

I repeat the exercise at the office over the course of the week, taking the time to stop and breathe whenever work gets too much. Each time, I’m surprised at how rejuvenating it feels, like blinking your eyes open after a long nap.

The verdict:

Wax’s humour is often grating, but out of the three books, I find her combination of science, spirituality, and common sense makes for the most accessible read. There’s less consolatory waffle and more insight, such as when she explains how the brain registers thoughts and emotions. (In scientific terms, the latter are ‘thoughts with bells on’, a distinction I find strangely comforting when an interviewee calls to cancel last minute and I resist the urge to scream. Emotions: 0; Sophie: 1.)

In summary:

One week into Project Mindfulness, Sophie 2.0 is not, strictly speaking, improved. I don’t feel happier with myself or less inclined to self-flagellation. But between my plant-filled hiding hole and regular breathing practice, I’ve had a better week than I expected.

I still believe a healthy dose of scepticism around self-help books is important—even necessary—but I’ll concede my prejudice against them was mostly snobbery. The hardest part of this experiment wasn’t taking the time to read the books or putting their advice into practice: it was trying to be open-minded enough to give them a fair chance.

Some of their advice was helpful, and some of it wasn’t, but the act of reading itself forced me to interrogate my own biases and expectations. The library has plenty of options for every kind of reader looking to better themselves (or make fewer mistakes), and while Hygge didn’t cut it for me, I’d happily pick up Cheryl Strayed’s Tiny Beautiful Things or Esther Perel’s The State of Affairs.

Moreover, the introspection deep reading requires is, perhaps, a kind of mindfulness training in itself: the art of learning not just what you think, but how and why. Getting in the driver’s seat of your own brain takes a surprising amount of practice, and as with most of life, it starts with the little things.

Yes, even succulents.

This story was sponsored by the National Library Board’s National Reading Movement.

The Little Book of Hygge and thousands of other titles are available for loan anytime, anywhere via the NLB Mobile app. Download it here to get started.

Would you let self-help books help you? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.