All images by Cheryl Tang except where otherwise stated.

M Ravi is having a busy day. When I finally locate him, half-hidden behind a wall of orchids at a cafe in Capitol Piazza, he rises to shake my hand firmly and sits back down, with enough haste to suggest he has something to get back to. Apologetically, he asks if we can delay the interview a few more minutes; he just filed an important lawsuit this morning, and needs to finish crafting a Facebook post to announce it.

His clients, five SBS Transit bus drivers, have just sued their employer for breach of contract, alleging they are owed years of overtime pay. Apparently, the case could have implications for thousands of other bus drivers. “How should I word this?” he muses aloud, still staring at his phone. “Five SBS bus drivers just filed a class-action lawsuit …”

Hang on, I interject. I thought class-action lawsuits weren’t a thing in Singapore?

“Really?” he asks. “Are you sure? I don’t want to say anything misleading.”

I think so, I reply. We puzzle over class actions vs. representative actions until I insist I’m not qualified to be having this debate, Google ‘class action lawsuits Singapore’, find a brief written by a law firm, and hand my phone to him.

He eyeballs it and sighs. “Oh,” he says. “Hmm, okay, you’re right. Let’s not say class-action lawsuit.”

He passes my phone back to me, finishes typing out his post, reads it aloud one last time, and puts his phone away, giving me his full attention.

“I’m so glad you’re here,” he says.

Ravi has hit the ground running since he got his practising certificate back in July. On the day of our second interview, two days after the first, the papers report that Ravi is acting for Dr. Roy Tan, one of the plaintiffs in the combined 377A challenge to be heard in November.

On top of that, there’s Daniel de Costa, charged with criminal defamation for an article he wrote for The Online Citizen. John Tan, Vice-Chairman of the SDP, on whether having committed contempt of court disqualifies him from contesting in the upcoming General Election. The couple in their 30s who wore anti-death penalty t-shirts to the Yellow Ribbon Prison Run in September. On top of this, Ravi mentions several ongoing human rights cases he’s supporting in other countries: India, Tanzania, Indonesia.

Cases involving LGBTQ rights, capital punishment, freedom of speech, and voting rights all feature heavily in Ravi’s work history. You don’t have to be a law student or constitutional law geek to have encountered one of his cases; some of the most significant and well-reported legal matters since the mid-2000s, such as Tan Eng Hong v. AG (a landmark 377A challenge), Vellama d/o Marie Muthu v. AG (‘the Hougang by-election case’), and the battery of Yong Vui Kong cases (regarding the mandatory death penalty for drug trafficking) were all fought by him. In a 2014 paper on cause lawyering in Singapore, legal scholars Jothie Rajah and Arun Thiruvengadam suggest that several politically sensitive cases might never had their day in court had Ravi not acted as counsel.

Ravi’s more well-known clients tend to fall into two categories: underdogs, or thorns in the government’s side (the Chee siblings, Roy Ngerng, Han Hui Hui, and Alan Shadrake are all former clients). Public interest lawyers in Singapore are few and far between, and if someone’s tried to challenge 377A or had the government after them for defamation in the last decade, chances are they had Ravi by their side in court.

For the last four years, however, Ravi’s appearances in the media centred on something quite different: his very public struggle with bipolar disorder, with which he was diagnosed in 2006.

Despite a personal history of getting on the court’s nerves (local legal folklore is peppered with instances of Ravi getting his knuckles rapped by judges), hints of real trouble began to surface in the early 2010s: a public dispute with a client, increasingly bizarre social media posts. In 2015, the Law Society moved to suspend his practising certificate, alleging his mental health impaired his ability to practise.

Press and public alike lapped up the drama that followed. After a series of increasingly high-profile incidents, things eventually reached a nadir with the Jeanette Chong-Aruldoss/Sri Mariamman temple episodes, for which he was ordered to undergo 18 months of mandatory treatment at IMH in lieu of a jail term.

To this day, the media’s preoccupation with his mental health frustrates him immensely. (At his hearing, he explained that his behaviour was a result of his condition, but nonetheless “mortifying” and “completely out of character”). He would much rather people focus on his deeds, not his diagnosis, and tells me that “things are definitely better” and he’s “in the best place now”, having received plenty of support from his friends and colleagues.

I don’t get a straight answer from him over whether he’s questioned if his condition might affect his ability to practise. He reminds me that the more public complaints about his conduct took place when he was unwell and not technically practising, and insists that no client has ever complained directly to him, a claim impossible to verify. This said, given the public nature of his illness, and the conditions attached to his treatment—including going for sessions at IMH and taking blood tests when required—he is, perhaps, subject to more oversight than any of the umpteen lawyers struggling silently with mental health issues.

The sixth of seven children, Ravi’s childhood was marked by poverty and domestic violence as much as mischief and tenderness. His father, who took his fists to his wife and children in between stints in prison, once ripped 9-year-old Ravi’s breast pocket from his school uniform in a bid to get at his pocket money. By contrast, he describes his late mother as an “intensely gentle soul” with a limitless capacity for giving (she once gave her own sacred marriage pendant to help out an elderly neighbour against the advice of Ravi and his sister, who doubted the woman’s indigence.) He repeatedly cites her as one of the greatest influences on his life.

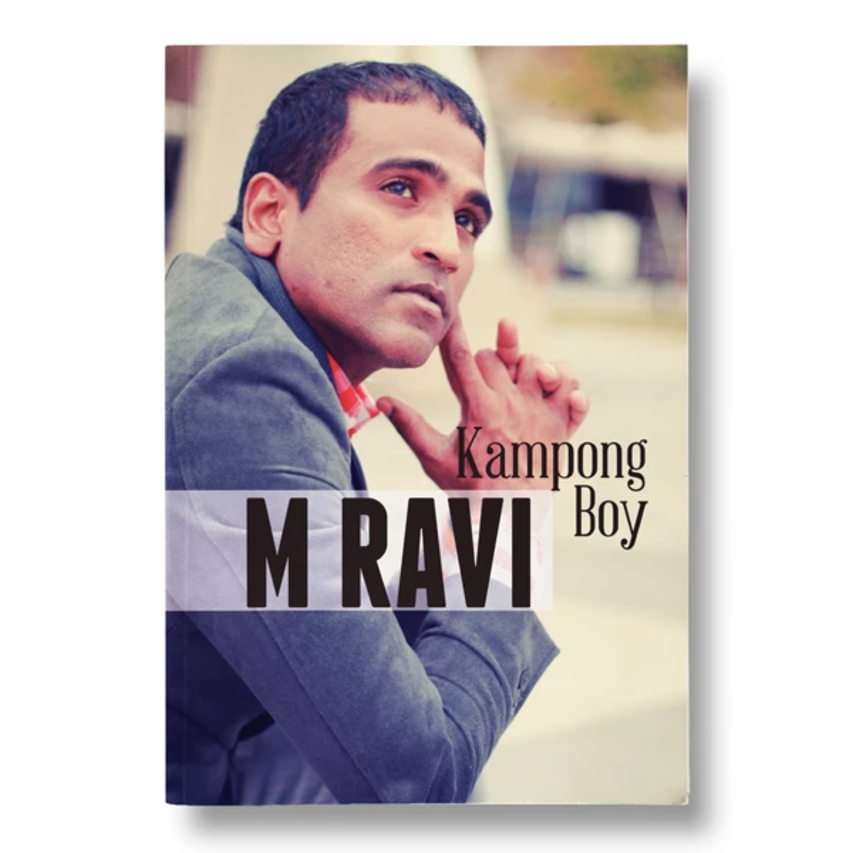

Between reading Kampong Boy, his 2013 autobiography, and talking to him over coffee, it’s impossible not to see the seeds of adult Ravi in his younger self. Despite the 40-year-plus age gap, both the boy and the grown-up possess a degree of disregard for convention, an inability to accept the word ‘no’, an even greater inability to stomach unfairness, an impressive aptitude for hustling, and an irrepressible idealism.

Frustrated at the uneven playing field between himself and other young Tamil debaters, whose family backgrounds and means gave them access to coaches he did not have, Primary 3 Ravi slept all night outside his sister’s teacher’s flat to convince the man to help him prepare for a contest. (It worked; he won, though not before his mother, annoyed by his non-stop practising, started calling him ‘an irritating parrot’.)

He helped dissatisfied patients at the local hospital lodge complaints with the hospital’s PR department, and took part in a fire-walking ceremony at the Sri Mariamman temple despite being several years underage. As a student at Anderson Junior College, he improvised his way into a meeting with J.B. Jeyaratnam, the then-leader of the Workers’ Party (better known by the catchy ‘JBJ’), ran for student council, and then voluntarily resigned his position when the discipline master asked him to rat out his peers for playing football in their uniforms.

After graduating from NUS with a degree in Political Science and Sociology, he crowdfunded his law degree from the University of Cardiff with help from four benefactors—friends, mentors, and former teachers who agreed to loan him the S$80,000 he needed. Upon returning to Singapore, he enjoyed a brief stint as a Tamil-language newscaster before getting called to the Bar in 1997, beginning his legal career with run-of-the-mill criminal and civil litigation.

Things might have stayed that way, because newly qualified Ravi had no intention of going into human rights law. He’d never seriously thought about it, but he also had more important things to do, like build his career, pay off his loans, and look after his mother, who was mired in her own struggles with clinical depression. In 2000, she took her own life while Ravi was at a meditation course. Her death devastated him, and for a while, all his energy went into carrying on with life as normal.

The turning point only came in 2003, when JBJ asked him for help with an urgent case. A young Indian Malaysian man, Vignes Mourti, had been charged with trafficking heroin into Singapore and sentenced to hang. After a long string of failed appeals, Mourti had only one option left: to try to overturn the original conviction and obtain a new trial.

According to Ravi, Mourti’s father had asked JBJ to take over the case, but the latter, being an undischarged bankrupt, was not able to represent him. He asked Ravi to give it a shot.

The younger man hesitated. He’d never done a capital punishment case, and Mourti was just a week or two from the gallows.

“I told [JBJ], maybe go ask your son. But he said he’d already asked a few lawyers and they don’t want to … it’s going to be complicated, stressful, they don’t have the research resources. And last-minute, the courts would never re-open a case. It was so messy,” he tells me.

“But I was convinced the guy was innocent, and the manner in which he was treated by the court … I felt it was terrible, like they’d rushed through the process. And that affected me, plus there was no outrage in the legal sector, in the legal community … it was disgraceful.”

They lost, but the case, plus the grief and anguish Mourti’s family experienced, ignited his innate righteousness. His outrage moved him to found the Singapore Anti-Death Penalty Campaign in 2005 (it still runs today) and slowly angle his career towards human rights, particularly capital punishment cases.

“I just had to do it at all costs. Basically, there was my strong opposition to the death penalty, and knowing these people were so poor, lacked education and all that, and their youth …” he shakes his head and trails off.

“I became very clear in my direction. Human rights lawyering is fashionable now, but at that time, I basically said, ‘I’m a human rights lawyer and I’m going to do this’. I didn’t wait around for someone to give me the title. I just did it. I felt I needed to break the impasse here, and that I should trailblaze as a human rights lawyer because it has a place in Singapore.”

The mid to late 2000s passed in a non-stop stream of networking, training, and work. He agreed to represent a young Nigerian football player, Amara Tochi, in another drug-trafficking case here. A search for regional support brought him to Hong Kong, where he met legal and political eagles Albert Ho and Martin Lee. This was followed by a flurry of international travel, including a two-week course in Human Rights Law at the Central European University, an internship at the European Parliament, and early research collaborations with Amnesty International and the London-based Doughty Street Chambers, arguably the Mount Olympus of human rights and civil liberties law. (Ravi lists one of its co-founders, a Queen’s Counsel and one of the world’s top human rights barristers, as a referee on his CV; I reached out to him for comment, but did not receive a reply in time for this story.)

Back home in Singapore, his client record picked up. Within a few years, he acted for Tochi, Chee Soon Juan, a Falun Gong protester, and campaigned for a Vietnamese-Australian drug trafficker named Van Nguyen, taking his case to the UN. In 2009, he took on Yong Vui Kong’s case.

Legal appeals open up possibilities. They also pave the way for a marathon slog with no clear end date in sight. If the Court even gives you permission to do so (leave to appeal is not automatic), your counsel either needs to find an argument which has not been made before, or somehow convince the court they made a mistake, either in terms of substance or procedure. For defendants on death row, there is the added layer of clemency petitions, which come with their own sub-string of appeals attached. Each new attempt extends your time in limbo by several more months.

Across both routes, each time you don’t succeed, your options slowly dwindle as each progressive argument gets tried and rejected. (You also need to not run out of money while you keep trying to find something that works.) Depending on you and your lawyer’s tenacity and/or ingenuity, you can drag the war out for years, and sometimes—very rarely—win a battle that counts. But more often, defendants either run out of options or willpower to keep going. Hope can be infinitely precious until it turns into a poisoned chalice.

Vui Kong’s case(s) went on like a tennis volley at Wimbledon.

The courts would hand down a decision. Ravi would counter with a new idea. The courts would say no again. Ravi wouldn’t take it. Rinse and repeat. But as play went on, it coincided with several major developments, including a temporary pause on hangings around the year 2010, and significant amendments to the Misuse of Drugs Act. (Rajah and Thiruvengadam note that Ravi’s contributions cannot be isolated as “the pivotal cause of these developments, but are nonetheless significant in the larger scheme of factors leading to a change in policy.”)

In 2013, Vui Kong became the first drug trafficker on death row to have his sentence reduced to life imprisonment with caning. Ravi had done it: through his sheer refusal to say die, he’d saved a man from death.

Eugene Thuraisingam, a longtime friend of Ravi’s, former colleague, and renowned lawyer in his own right, told me over email, “[Ravi] has made significant contributions to the legal field in Singapore. Many of the most significant constitutional law cases were argued by him. This has provided the rest of us with very rich case law which we can use and build on.”

“In particular, I have utmost respect for how he unflinchingly persevered in acting for Yong Vui Kong. Challenge after challenge was filed in Court, fought hard and met with bitter disappointment. Some accused him of giving Yong and his family false hope, but he persisted until he finally succeeded in saving Yong from the gallows. Yong would not be alive today if not for Ravi’s persistence.”

In a field inclined to convention, discretion, and caution, Ravi had shown an unusual penchant for risk-taking, frankness, and independence. He had also, by his own admission, proven to be less skilled with something quite important for lawyers: strategy.

“I know I’m not very savvy at looking at minefields which are ahead,” admits Ravi. “Because I do have this condition and all that.”

We round back to this concept several times. With each cycle, he clarifies this further: in his passion for his human rights work, he neglected to balance these with commercial cases (though as long as he works pro bono, some financial opportunity cost will be unavoidable).

He’s not great with “watching [his] OB markers” either. Across our meetings, he makes numerous criticisms of members of the judiciary and the government, only to glance hurriedly at my phone and add, “That’s off the record.” (Arguably, this goes beyond just OB markers; in July, within the first week of getting his certificate back, the CPF Board and Ministry of Health issued a statement disputing a video he put out for one of his clients, alleging that its claims were ‘misleading’. A few weeks later, he publicly withdrew a statement he had made in a separate case involving a Malaysian drug trafficker.)

However, he insists that he faces a lot of constraints, too. The cases he takes up are controversial and contentious, and the mainstream media doesn’t always cover him fairly (“It’s crap, they’ll spin and spin and spin”). He faces a lot of doubt from naysayers who insist he should just move on, be smart about it, and not get into trouble.

Then there’s the personal cost of cause lawyering. The more you care about your work, the more you see it as a moral duty, the higher the stakes of each fight; if you fail your client, you fail yourself too. There’s the stress of going to battle on uncharted territory (civil liberties and constitutional jurisprudence is still in its early stages here, and Singapore lacks overarching human rights legislation in the way of the UK’s Human Rights Act). The loneliness of taking up causes few others are willing to step up to (though he makes sure to credit those who have, mentioning Peter Low, Remy Choo, Suang Wijaya, and Eugene in our conversations).

The risks, both figurative and literal, of being willing to act for antagonists of the state. The never-ending demands of being strong for clients, rushing from case to case, living deadline to deadline, always giving more, getting very little back.

Add mental health to the mix, and the toll of all this would cripple anyone. Blazing a trail had indeed brought him, several times, to the brink of burning out.

Eugene concurred with this grim assessment of the cost of cause lawyering, although he also felt Ravi was “by and large to able navigate this minefield”.

“There are challenges and great risks in the area of work Ravi undertakes,” he said. “There is little, if any, financial reward. But just one wrong move, one mistake can land one in extreme trouble in this area.”

On Ravi’s part, he believes he’s learned from past mistakes. “As I progressed, I learned to navigate the challenges I faced.”

In particular, he talks extensively about how he’s recognised the need for solid research support (“not just 1 or 2 people, you need a whole army. And the mind for it. Research can’t be wishy-washy, it has to be top-level”) and taken steps to amass this, both locally and internationally.

Did you ever worry that you weren’t up to the job? I ask. Did you ever doubt yourself?

“No, never.”

What gave you that confidence?

“I’m passionate about the work. Inherently, I’m a responsible person. I will go and do the research. But the framework is there, there’s nothing much to really … I come at this from a very sociological background, like, what is law? It’s really not too complex. Sociology and political science are much more complex.”

Seeing my eyebrows jump to my hairline, he adds, “But you’re right in that you need to be armed with research support. I didn’t just jump into it without any support. I will say that I was apprehensive initially, I didn’t know I would be up to the mark.”

I suggest that in work like his, not being up to the mark can’t be an option. If you screw up, somebody dies, I tell him. (“Yeah! Exactly.”)

So you can’t afford to mess up.

“But nobody’s going to come forward and act for these cases anyway. If you act, that’s good. If you don’t act, no damage, because the person is going to die anyway. And no one is stepping forward anyway. That’s the crux of it.”

At risk of flogging a tired metaphor, litigation is a game of chess. Every move is a direct response to the preceding one, but the pieces are in constant motion. Unexpected developments can knock out a play you had up your sleeve. Calculated risks can pay off, but sometimes they don’t. Sometimes you try to plan several moves ahead—which requires you to know your enemy, which requires you to know yourself.

There are many valuable weapons in the litigator’s arsenal: tenacity, fearlessness, intelligence, the ability to both see the big picture and the tiniest details, a solid team, money. Less well acknowledged is self-awareness. As Sun-Tzu put it in The Art of War: “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.”

Asked to describe Ravi in three words, Eugene tells me he is “motivated, driven, and courageous”. A good ⅓ of Jothie and Thiruvengadam’s paper is devoted to exploring Ravi’s contributions to the legal field locally, and suggests that his “singular” career, “visibility,” and “prominence” possibly, if not probably, “created the conditions of possibility for other lawyers to step up and play the role of cause lawyer”. (However, they stop short of describing the man himself, noting that they lacked an understanding of his motivations.)

So I ask him what these are.

He clarifies that to him, cause lawyering inherently uplifts humanity, given how its issues affect society at large: access to justice, discrimination. “Basically, it empowers humanity. Strengthening core principles.” Of these said principles, his own top 3 are compassion, justice, and humanity.

What do justice and humanity mean? Actually, he says, take out humanity. “I think compassion … actually I would just say love. Because compassion encompasses everything to me.”

Prompting him for his strengths as a lawyer yields a long pause. I narrow my question, asking what makes him a good human rights lawyer, and then the answer is forthcoming: human rights lawyering takes grit, especially in navigating difficult constitutional challenges. Tenacity, especially when it comes to research. The willingness to do all this pro bono. And fearlessness.

By this time, I’m wondering how our conversation has devolved into a job interview/personality quiz, but I press on. What do you think your weaknesses are? He doesn’t understand. I rephrase my question and offer some of my own shortcomings as examples. Following the clarification, he hesitantly suggests he should pause more in the actions he takes, then walks this back. I ask if he means this in a ‘look before you leap’ sense.

“No, I always look before I leap. The thing is that … I don’t want to overcommit myself to pro bono work. My portfolio is over 50% pro bono, which is highly taxing in terms of time and cost. Friends have asked me time and again, is this back to square one? So what I’m saying is I have a tendency to go into too much.”

You need to know your limits, I nod.

“Yeah. But other than that, I really don’t have much comments on this.”

Of course, Ravi does not need my validation or anyone else’s, and he knows this. He’s finally got his certificate back, and the 3.5 year break from the courtroom was long enough.

He’s now working at Carson Law Chambers, headed by Lim Tean, the leader of the People’s Voice Party. On top of his caseload, he’s been working with Andrew Loh of The Online Citizen on a new media channel, RAVISION, where he posts content explaining human rights concepts in layman’s terms, updates on his own work both locally and internationally, and talks with other human rights activists and lawyers in the region. (“It’s basically to inspire human rights lawyers in the region, and not just them, but corporate lawyers … they could go into their corporate offices but still help out with my research.”) He’s also looking to add new blood to his team, in the hope of introducing them to the workings of human rights law.

“It’s all very exciting,” he says.

Is this a comeback?

It is, in the sense that he claims to have received “rousing support” from the public (“over 1,000 likes on Facebook and everything else”), as well as encouraging messages from both strangers and members of the legal community. But at the end of the day, he feels he’s in a position to be more true to himself than he was in the past.

“I think that more and more, with more experience and knowledge of myself in relation to society, I’m more at ease.”

In addition to being at ease with himself, it helps that he’s always been at ease with his work. In a field notorious for the absence of any clear answers, he claims to have always found it easy to identify when an injustice has been committed. The intellectual complexity of human rights law is balanced out by the joy and excitement he gets from reading about it, so it’s not something he finds difficult. He has never once doubted if he’s doing the right thing. So despite the immense sacrifices he’s had to make, the pain and hardship he’s endured, he’s never once doubted himself. And he thinks his work is absolutely in his comfort zone.

“It’s definitely within it. I’m a human rights lawyer. If I don’t do this work, it’s not in line with who I am. This is a calling.”

It is also an impossible claim to adjudicate. The man who ought to know best does not, by his own admission, always know his own limits. I’ve only chatted with him for a few hours, done a few weeks’ research and read his autobiography. Only the work he’s done, and the work he will go on to do, can achieve this.

So perhaps neither of us knows how far he can go. But as we wrap up with photos on the steps of the National Gallery, also known as the Old Supreme Court, Ravi perched halfway up and adjusting his blazer, I think I can hazard a guess at where he now stands: in between the world as it is, and the world as he thinks it ought to be; between the man he thinks he is and the champion he believes this country needs; between hope and self-delusion.

It’s the same gap that human rights law, with its insistence that humanity uphold its best values even when it’s sunk to its very lowest, attempts to fill. If you can overlook the fact that there are virtually no other takers, he is, in this sense, the perfect man for his job.

Have something to say about this story? Tell us at community@ricemedia.co.