Top image: Screencap/Mediacorp

– Although our politicians have always condemned racism, they have hesitated to discuss it in substantive or meaningful ways. This silence at the top has not kept pace with how conversation on the ground is evolving.

– Focusing only on obvious examples of racism limits progress, and avoids responsibility for how these outcomes are the result of political or policy choices.

– Nonetheless, recent shifts in how our leaders talk about race point to opportunities for change. We explore how the different political parties in Parliament might achieve this.

If there was a playbook for how our politicians respond to racism, it would go something like this:

Condemn racism while recognising its continual threat. Affirm the public space as one for all Singaporeans. Cite the pledge. Appeal for mutual respect and understanding. End off with something along the lines of “racial harmony is a work in progress, but we can always do more”.

Minister Lawrence Wong’s speech at the IPS/RSIS conference on Friday followed this template, but with several noteworthy additions. In it, he called on Singaporeans to recognise that minorities face difficulties ‘in all aspects of daily life’, and spoke of the ‘real hurt’ that discrimination can cause. Significantly, he stated that we should be “upfront and honest about the racialised experiences various groups feel’ and ‘begin civilised discussions’, grounded in empathy, good faith, and a willingness to listen to all.

It’s a thoughtful and earnest speech, and a step in the right direction. Nonetheless, one can’t help but notice that at the state level, several of the biggest and most controversial incidents of the last two years—the ePay mess, the investigation of Raeesah Khan, and most recently, the PA/Sarah Bagharib debacle—yielded scant progress in how we talk about race.

Rather than fruitful discussion, it is more common for a news-making incident to end in police reports and ‘missed opportunities for dialogue’. For the most part, the developments in conversation on the ground —or appetite for this—have not been matched by our leaders.

No politician has denied that racism exists here, or portrayed it as anything less than unacceptable and dangerous. However, this is often softened with qualifiers that the vast majority of Singaporeans are not racist, that racism exists in every country, and at least it’s not as bad here as it is elsewhere—the race equivalent of ‘not all men’, if you will.

Earlier this month, I argued that the Dave Parkash incident exposed some double standards in how we think about racism. We can observe a similar divide at the state level, where politicians leap to denounce racism, but hesitate to weigh in more meaningfully.

Tan Boon Lee’s harassment drew unanimous censure, with all three parties in Parliament citing a zero-tolerance stance towards racism. However, few examined the notion of ‘preference’ in interracial unions, and whether such views are acceptable today.

While there was agreement that the PA was wrong to use Sarah Bagharib’s photos without her consent, politicians side-stepped the question of whether the affair was racist or merely ‘culturally insensitive’. Notably, MPs from the PAP and WP declined to comment on the incident when approached by TODAY.

It’s fine that there’s no public consensus on how to define racism—our understanding of the concept is still evolving. The problem is that almost no politician dares to push these boundaries.

With a handful of exceptions, few politicians have dared to go beyond the obvious, and examine racism as outcome- rather than intention-focused, systemic, or explore how it intersects with class and other social determinants.

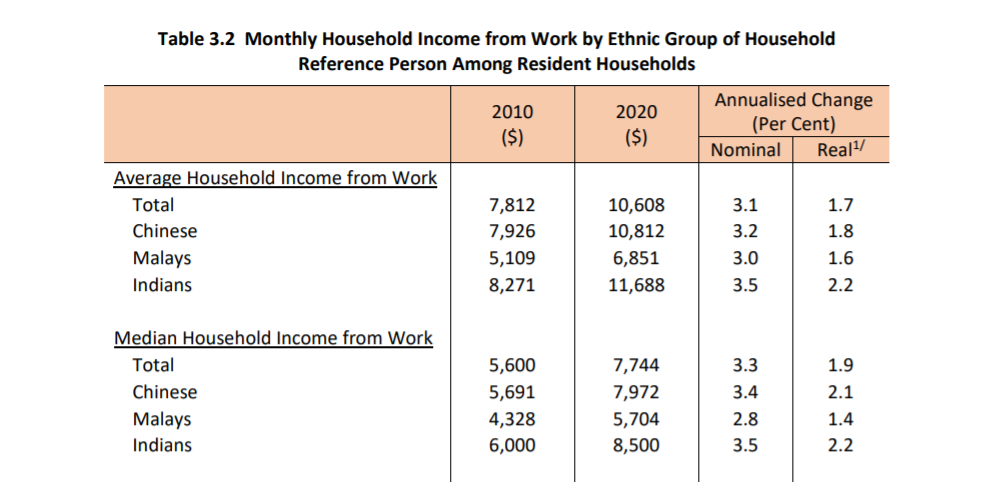

This goes beyond interracial marriage and squabbles over ‘cooking smells’. Questioning the financial outcomes of HDB’s Ethnic Integration Policy, for example, remains a minefield, as does exploring links between socioeconomic factors and racial disparities in health outcomes, or income gaps. The recently released 2020 census showed that the average household income of Malay families is the lowest of all ethnic groups, which has not changed since 2010.

The thing is that the government has long recognised that disparities exist, and taken some steps to look into these. Most recently, in the last couple of months, workgroups were set up to explore health outcomes in minority groups and to boost home ownership amongst Malay families.

These would have been valuable conversation starters on the material aspects of racism. Working towards solutions is important, but implicitly recognising that a problem exists is not the same as ‘being upfront and honest’ about it. Skipping this just looks like avoidance.

Nonetheless, in the last couple of months, there has been a subtle shift in how racism is framed.

Minister Wong’s speech is the latest example, but Minister Shanmugam’s comments following the Dave Parkash incident raised some eyebrows. In a longer post on cohesion, President Halimah reflected:

Such displays are so hurtful because we thought that we had done so much to protect our cohesion until we are shaken from our belief … We wonder whether these are one-off incidents or reflective of a larger problem.

Despite this, there has been little acknowledgement of the accounts of everyday racism flooding social media. While these were referenced in Minister Wong’s speech, and younger politicians, like the PAP’s Nadia Samdin, WP’s Nicole Seah, and Jess Chua, leader of the PSP’s Youth Wing, have posted statements on social media, many more have remained silent.

It’s understandable why no one wants to open Pandora’s box. Racial and religious harmony are the most out-of-bounds of the OB markers. Nobody wants to be accused of playing identity politics, grandstanding, stoking ‘culture wars’, or risk alienating voters.

Ultimately, however, the milquetoast ‘we must do better’ comments enable self-preservation. If the focus remains on incidents of obvious malice, this allows deeper questions about racism to go avoided and unanswered.

Probing further entails recognising that outcomes are the result of choices. It also raises expectations about when these choices will be reviewed, and who will be responsible for this.

Here, the PAP’s history works against them: as the ruling party since independence, they shoulder the most responsibility going forward.

As a start, they will need to introspect on, and acknowledge, Lee Kuan Yew’s troubling views on race and eugenics as well as past comments by its MPs. They will need to examine how portrayals of race in their communications can be less one-dimensional, including guarding against stereotypes about the ‘Malay problem’.

More significantly, where evidence points to racial inequalities (such as in housing, educational outcomes, and income), nuanced and thorough reviews should be conducted. As the dominant party, many of the gateway actions to doing this—such as making more race-based data publicly accessible—rest with them.

None of this needs to amount to fuelling tribalism or pretending race doesn’t exist.

For example, Minister Wong is right to say that Chinese privilege can’t be addressed without involving generations still aggrieved by the loss of Chinese-medium schools and dialect erasure (decisions which, it must be noted, were the result of government policy). But what if reviewing SAP schools was framed as increasing educational access for non-Chinese students, rather than attacking Chinese-ness? Or the EIP about mitigating inequality, rather than a premature rush towards race-blindness?

Opposition parties might have limited decision-making power, but they are neither blameless nor helpless. Chiefly, they need to not only condemn racism, but acknowledge their culpability in allowing it to fester.

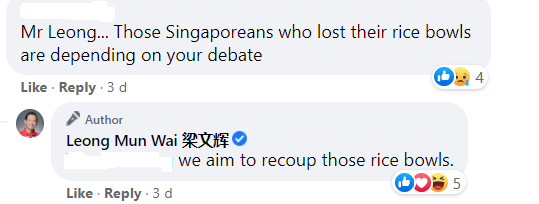

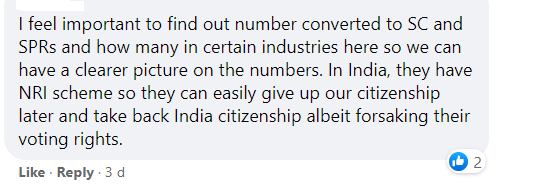

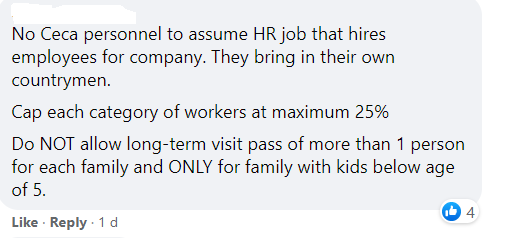

As a party, while the PSP has come out multiple times to denounce racism and xenophobia, it has not acknowledged how its supporters’ enthusiasm for reviewing CECA often shades into these, or attempted to rein them in. Nor has it addressed how its own politicians’ remarks sometimes veer into dog-whistle territory, like Leong Mun Wai’s hand-wringing over hawker centres serving ‘more and more foreign food’, or ‘recouping’ Singaporean rice bowls from foreign PMETs.

This has to stop. Letting mutters about ‘CECA personnel’ pass unchecked is only a few rungs down from Nigel Farage’s legitimising of ethno-nationalism—the kind that started with ‘British jobs for British workers’ and ended in minorities being told to ‘go back where you came from’ post-Brexit.

(For that matter, the PAP is equally guilty of ignoring the politicking carried out by groups like Fabrications About the PAP. Despite all the talk of mutual respect, I have not seen one politician publicly call out Shamsul Kamar.)

The WP, meanwhile, has been ultra-cautious about stepping up to the discussion. While several of its members have made statements on social media, and Raeesah Khan recently asked several Parliamentary questions about racism in schools, the party has said nothing groundbreaking since Sylvia Lim’s speech on a post-racial society last September.

The proposals in that speech, which argued for a review of the CMIO model, the EIP, and community self-help groups, amongst others, should be revisited. After all, their GE2020 campaign was based on the checks-and-balances pitch; this is the standard they will be judged by.

This dynamic is hardly unique to Singapore. Worldwide, political willingness to move on controversial issues is often dictated by the public mood. Politicians don’t usually take a stand until it becomes more disadvantageous to keep quiet than speak up.

All the same, the issue is gaining momentum, and by waiting too long to say anything meaningful, everyone stands to lose: the PAP’s potential for a rebrand, Opposition parties who market themselves on progressivism, and the country as a whole, for a chance to learn together. The irony is that silence from the top is the ultimate indictment of the state of Singapore’s social fabric: if harmony is as valued as all have claimed, then we should survive talking about this.

Shattering the taboo around race will be both uncomfortable and politically risky, but it can only make this country stronger. It is also an opportunity to demonstrate real leadership.

If you have thoughts on this piece, a tip-off you’d like to share, or just want to say hi, drop us a message at community@ricemedia.co. And if you haven’t already, follow RICE on Instagram, Spotify, Facebook, and Telegram.