“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” wrote philosopher George Santayana in The Life of Reason: the Phases of Human Progress.

The battle of words between Law Minister K Shanmugam and Oxford research fellow PJ Thum earlier this month proves that absolute truth in history is difficult to arrive at. And truth is also often lost in the way each party attempts to present their version of the facts.

Irwin See, who holds a Masters of Studies in Modern History from Oxford University, knows this all too well. And the private tutor hopes that students in his General Paper (GP) class would not just get sucked into the drama of Shanmugam vs PJ Thum, but actually understand the value of history and truth.

“We could say that both sides were right but also wrong in certain ways,” Irwin says of the hearing by the Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods.

“What is important for me is getting students to see that there could be a diversity of views which could all be correct in certain aspects, but you really need all of them together to get the full picture.”

Truth is also not something that “you hammer on the head of the other person”, the GP tutor at Irwin’s Study adds. It’s not simply about what one thinks is true, but also how one engages the listener and communicates his ideas.

“If you don’t allow the other side to voice their views, or don’t have the patience to listen to the other side, then no matter how right we are I think we might have lost a bit of humanness.”

The Select Committee saga is just one of the many current affairs issues that Irwin picks from the headlines for students to discuss in his weekly two-hour lessons. They may be complex or even sensitive topics that students may not feel comfortable expressing their views on. But Irwin’s main goal is to challenge their preconceptions and encourage them to think more critically about the issues happening around them.

After all, GP is such a broad subject covering a wide range of topics and issue. To score an ‘A’, students have to display a deeper level of understanding and analysis – more than just merely recalling news articles in their essays – if they want to do well in the A Level exam.

The willingness to be patient, to sit with views that are diverse from yours and even opposing, without immediately slamming them or shutting the door is a very critical skill.”

A common pitfall is being trapped in an echo chamber where students are only exposed to similar views and conform to a narrow perspective on issues. This problem is exacerbated by the algorithms of today’s social media news feeds, as well as the proliferation of fake news.

“The other thing I challenge my students to do is to cross over to the other side so that they actually listen to what other people think, even though they may not agree with it straight away,” says Irwin. “The willingness to be patient, to sit with views that are diverse from yours and even opposing, without immediately slamming them or shutting the door is a very critical skill. You don’t know who has the premium of truth, and often you may not have the whole picture.”

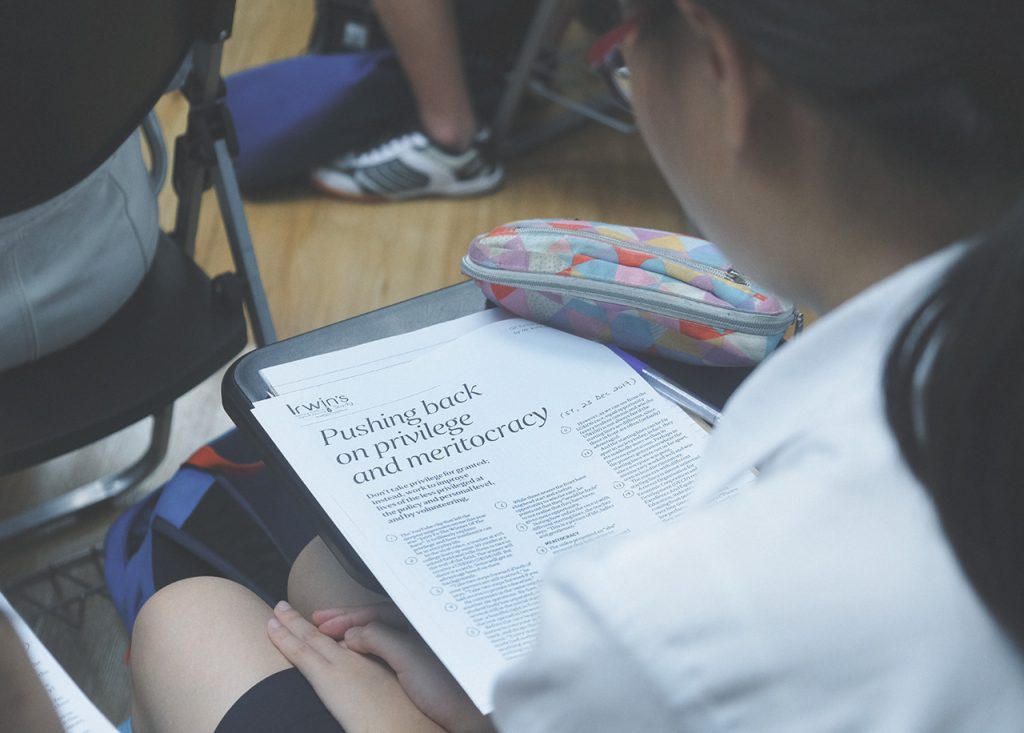

Often times, Irwin uses the Singaporean context to help students understand the importance of being receptive to opposing viewpoints. For instance, the issue of privilege – a hotly debated issue in recent times due to growing inequality – led to deep discussions in class.

“I wanted students to see that it’s very easy to swing to extremes on these issues. We can say that privilege should be demonised or that we should strive to equalise everybody. On the other hand, we may think it’s not a big issue at all because it happens anyway. Any of these extremes are incomplete and unhelpful.”

Another issue debated in class was meritocracy. Students were divided on whether success was truly a measure of how hardworking a person is or may be linked to other pre-existing factors.

In cases like these, Irwin’s goal is to get students to understand that such issues are not binary, and often a one-size-fits-all solution does not exist. “Through these discussions, I also get them to see that sometimes our perspectives are framed by our own hidden assumptions or blind-spots that we don’t normally think about. This is why we immediately jump to certain assumptions or make certain judgements.”

Many may associate him with the “elite” crop of Singaporeans. But elitism is only detrimental if it doesn’t improve the status quo. Speaking with him, I am struck by how Irwin is immensely humble about his past academic achievements, and hopes to challenge society’s perception about “elitism” by imparting not just knowledge but values to his students.

“A body of water that has no outlet will run stale. So there must be some outlet where we pass on that privilege and share with others,” he says.

“There are things that I believe students can explore and they should really go for it. But at the same time, they must understand that even when they have gotten that goal, it is not just for them to brag about or for show on their CV. Humility is in how they still carry themselves in a way that earns respect from people, not because of whatever achievements they have. Humble balance – this is the kind of balance which I hope students will be able to pick up from me and my classes.”

On the other hand, there were those who could breeze through the papers. With a strong command of the English language, they could score an ‘A’ simply by plucking a few strands of general knowledge or ideas from their head.

Irwin acknowledges that GP is not a straightforward, formulaic subject which students can see tangible results by purely memorising and applying concepts. The examination is part-content, part-language, and it takes a while for students to get used to a certain form of writing which requires them to display a level of balance and critical thinking.

It is easy for students who do not do well for the subject to slip into a zone of low confidence. But Irwin believes that through gathering more knowledge on a certain topic and open discussions in class, he can help students hone their worldview and build their mental framework to analyse issues. It may be a lengthy process, but ultimately this would greatly improve their critical thinking skills which they can then apply in their writing.

To score an ‘A’ for GP, students have to display a deeper level of understanding and analysis – more than just merely recalling news articles in their essays.

Irwin agrees that private tuition is not cheap, but also reminds me that he and the other tuition centres in Singapore provide a service. As long as parents and students continue to see the value in tuition, it would continue to be an important industry in Singapore.

“The real question could be not so much about how exorbitant it is, but more of how tutors should really strive so that they are providing the best education they can for students who go for their classes.”

But is this something that only high SES students can afford to give them an edge?

To Irwin, money shouldn’t be a barrier to education. Over the years, he has waived or discounted the tuition fees of students with financial difficulties so they can continue his classes without any worry.

At the same time, he continually value-adds his lessons so that his students do not merely come looking for a bump in their grades. Rather, he endeavours to equip his students with skills, values and world views that will take them beyond the A Levels.

To Irwin, this is the power of a subject like GP – not just educating the minds of young people, but tutoring their hearts as well.

Was GP the hardest subject for you? Did you spend your JC days memorising The Economist and Time magazine because your teacher sucked? Reminisce with us at community@ricemedia.co