My heart sank when I received my PSLE results. Falling a few points short of qualifying for Raffles Institution, 12-year-old me broke down in the school hall, my elitist dreams crushed.

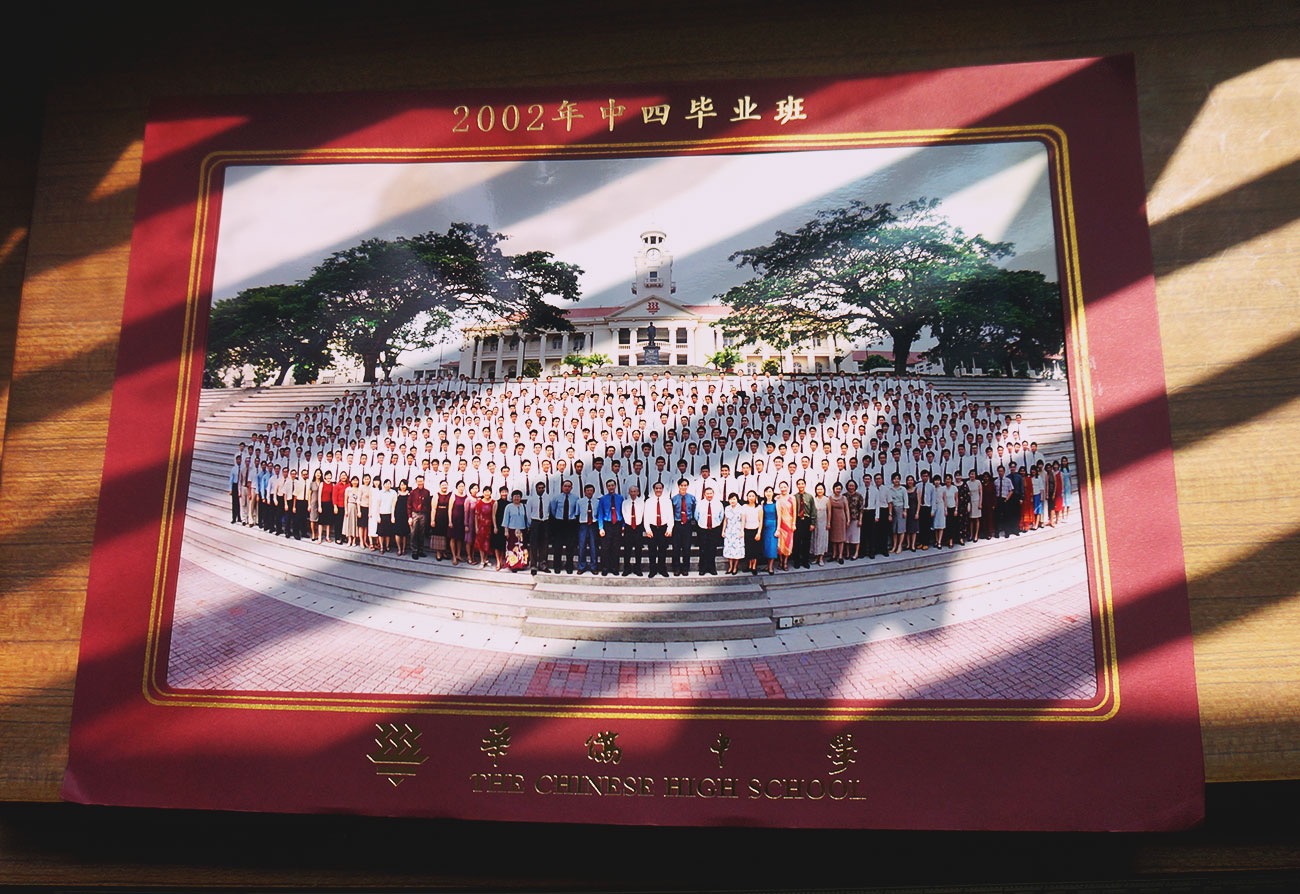

Qualifying for Chinese High was the next best thing, although I hated the idea of attending a “communist” school. At least, that was my impression. You can’t blame me for believing what people told me when I was 12.

A number of us (including myself) were RI rejects. However, for some, Chinese High was their first choice for its focus on Chinese language and character education.

From the moment I entered the school, the principal and school leaders were unabashed about informing us of our elite status. The principal would do so during school assemblies, only to be echoed later by teachers in a classroom setting.

Whenever we misbehaved, as boys often do, a good chunk of each lecture revolved around how we took our place in the school for granted. Being there was a privilege, and it lay on our shoulders to continue the prestigious legacy of the school.

We were also reminded that we should be thankful for the resources and the very upscale school facilities that we had.

And so from the very beginning, we were told that we were different and maybe better. No surprise that many of us grew up believing it.

To motivate us, teachers often sold us a dream of the straight path to success: get straight As for “O” levels, score a top scholarship, do your family and country proud. It was as unsubtle as that.

With the myriad of tests, common tests, level exams, and so on, doing well in anything provided some form of ego boost and adrenaline rush that imbued our mugging with a strong sense of meaning. As iron sharpens iron, being in the company of academic achievers, even the worst student felt the pressure to do well.

The environment of a top school is not unlike reality TV shows like Masterchef or Project Runway. Perform or you’re out, was always the subliminal message.

While academic pressure is a given for any school, I would argue that there is an overemphasis of it in elite schools. It always seemed like Chinese High was trying to beat RI for the top spot, making it clear that we were never competing with the rest of Singapore. It was just within those of us at the top.

This competition was our entire world. We hardly talked about other neighbourhood schools because we had no reason to. It didn’t help that our school was in the vicinity of Bukit Timah with hardly any neighbourhood schools around.

Having taught in neighbourhood schools, I now know how truly privileged I was. One key difference is the student to teacher ratio of 40 (in neighbourhood schools) compared to Chinese High’s 16.

As neighbourhood school students are less academically inclined (as indicated by their PSLE scores), they also tend to be more rowdy. Imagine one teacher handling a class for 40 rowdy teenagers; even the best students might not be able to reach their full academic potential just because the teacher’s attention has to constantly shift to keeping the class settled.

Teenagers are easily shaped by their environment. Competing with the best does elevate you in some way, while hanging out with people with disciplinary issues can drag you down as well.

As scholarships were a major focus in Chinese High, the teachers are experienced to handhold students through the application process, including writing testimonials to garner these scholarships. This is a luxury that neighbourhood school students do not have.

Finally, throw in business-savvy vendors who saw the profit making potential of a success-driven culture to market leadership camps, talks, and other training products par excellence to top schools like mine.

These specialised programmes equipped us with skills like public speaking, confidence building, and leadership.

During Secondary 3, we were able to go to Yunnan, China. It was marketed as an exclusive opportunity; something you might call a high-SES school camp.

Experiences like that dispelled any fear of going to a foreign country, which prompted many of us to dream about studying overseas for a more varied and exciting experience.

Many of my peers went on to top Junior Colleges, clinched highly sought after scholarships, and now fly high in the military and civil service.

I, myself chose a different route. After a few difficult conversations with my parents, my dad allowed me to leave JC if I could qualify for the university of my choice—the School of Visual Arts in New York.

Chinese High also had a very dedicated arts programme, or at least art teachers who advocated for quality art education. In one instance, they created a mini 2D animation studio for me as I was the first student who used 2D animation for my “O” level project. This, I believe, was essential in gaining my scholarship and entrance into my university.

I doubt I would have enjoyed any of these resources had I gone to any other school.

Long story short, I qualified, got a partial scholarship, left JC, and finished my 2 years of National Service. Before I knew it, I was on a plane to New York City to study in the school of my dreams.

Even then, I wouldn’t have clinched the scholarship or passed the entrance exam if not for the environment at Chinese High. I memorised about one to two thousand new words from the SATs word list; the ‘memorise and regurgitate’ academic rigour from Chinese High had trained me well.

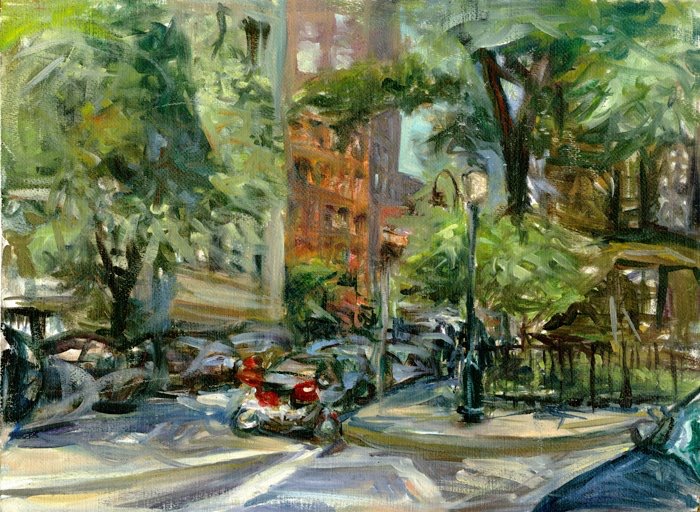

It was freezing when I arrived in New York City in late December. I saw snow for the first time, and the streets smelled of rubbish. When the orientation leader opened the door to show me my dorm, my first thought was, “Oh great, nice closet. Now where’s my room?”

That said, I threw myself easily into the school programme. Suffice to say, I lived up to the Asian stereotypes the local American students had.

I came to realise that my life experience thus far had not prepared me well for life in New York. Whenever a shelf toppled or a bulb went out, my American roommates proved to be well-versed with home-improvement skills. In contrast, the paper-heavy focus of our education had shortchanged Singaporean students of simple but essential life skills.

Lessons like these are now what I would consider the true privilege of studying overseas. Living in a completely different culture allows you to rethink certain priorities—the intense focus on exams in the Singapore system, does it really set one up for success? How do societies without that “Asian exam rigeur” create entrepreneurs and innovators?

Meeting foreigners and challenging my stereotypes of them would also go on to enrich my life and expand my worldview. Most who moved to New York had a common goal to pursue a grand dream, so it wasn’t hard to find common ground despite our differences. This international exposure would later equip me with the social skills to connect with people from all walks of life.

Whenever I question Singapore university students these days, I usually get unhappy responses about stress, backstabbing, and the competitive nature of their peers. In contrast, all I have are rosy memories of visiting galleries, painting in the studio, and the occasional beer pong.

New York City itself was sprawled with gorgeous and well-curated museums. My learning was not limited to my school, and the school actively encouraged us to visit the museums and galleries that were all just a bus ride away.

Most people study about Picasso or Van Gogh from a textbook. I saw the real pieces hanging on the museum walls.

Due to the nature of my studies, I quickly learnt how to strike up conversations at art gallery openings. It taught me to play the part of a cultured and learned person, which I now sometimes use during “atas” or “high-society” events in Singapore. Frankly though, I am usually just there for the wine.

As School of Visual Arts prided itself on being connected with the creative industry of New York, we were offered opportunities to score quality internships. I applied to Random House, a prestigious publisher, and was given a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to work alongside superstar designers like Chip Kidd, who designed the Jurassic Park logo.

Many of these big and important companies have their headquarters in global cities like London or New York. For my friends and I who went to other schools overseas, we were able to intern at these offices.

As we soon learnt, just the company names on your CV is prestigious enough to land you a job in banking and the civil service in Singapore.

For my other elite school friends, being enrolled at Ivy-league schools would provide them with the connections, interactions, and competitive environment that would set them up for professional success. After all, they competed with and learnt from the very best in their age group.

Upon graduation, I found work doing events branding and design.

Not many cities can pride itself on having created a creative economy like that of New York City’s. With the number of artists flocking from all over the world to pursue a dream in New York, art is held with a special reverence. Museums, galleries, fashion houses and art schools such as mine and the famous Parson’s also create that economy.

The diverse nationalities, talent pool and different sectors of the arts — music, visual arts, theatre, fashion, graffiti etc. cross-pollinate to create a creative economy that is unparalleled. This allows artists and businesses to dream bigger and hence explains why creative work would always be bigger and better in New York.

For art school graduates like myself, we had the privilege of integrating easily into this creative economy to develop into professionals, all through the connections established by the school.

Overall, an overseas education in a reputable university gives you an undeniable edge. Being forced to interact and present in front of extroverted Americans builds your confidence, and living independently and doing your own chores forces you to mature faster, which might not happen if you live with your parents.

I might have been lucky enough to afford the school fees not covered by my scholarship, but this alone would have been insufficient if not for how Chinese High had shaped me.

All in all, living five years in New York allowed me to see Singapore with new eyes. Even though our MRT breaks down every once in a while, I am reminded only of the rat-infested New York subway where the smell of urine often lingers.

And so I’ve realised that while things could always be better here, things could be worse as well. Living overseas provided me with the privilege of having a larger context to compare with. Small inconveniences don’t trigger me as much when I understand that even in developed cities like New York, many things are not up to par.

The fact is, most of our privileges are not immediately apparent to us; something I learnt while writing this article. One does not naturally think that being able to sit at the park chatting past midnight without the fear of being robbed is something to be thankful for.