I check my phone: It’s after midnight, and this will be the second time in the last week my neighbours are getting a late visit from local creditors with serious anger issues.

With one of the world’s lowest homicide rates, Hong Kong is, for the most part, a safe city, especially if you’re from a social strata that rarely, if ever, brushes up against the SAR’s nefarious underbelly.

the underground industry has been mushrooming since the 80s and 90s

For me it was a stop-gap situation. But for most, such as a single mother from Mainland China squeezed in with her two young daughters, it was the norm.

I met my neighbour, Maria* when I first locked myself out. A tiny and pregnant Filipina with a wry smile and spider tattoo on her collarbone, she took pity on me and helped me break into my room using an old MTR card.

A few months later her parents moved in with her, and not long after that, a crying baby arrived.

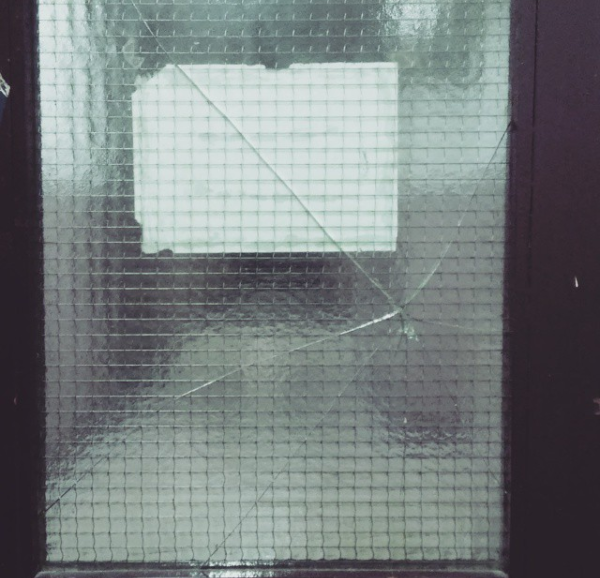

One evening I woke up to hear voices shouting outside my door. I could make out Maria’s voice, but the other was unfamiliar. And then a smashing sound, followed by silence.

I poked my head out to see her standing alone staring at a cracked glass panel in a door.

“Who was that guy?” I asked her.

“He’s just a crazy person,” she said, “He’s just making trouble.”

Maria’s mother and the baby were alone in that room, and both sounded distraught.

I opened my door, bleary-eyed and in my pajamas, and asked the five swaggering but skinny guys to leave. With one wearing glasses, another glaring behind a silly blond fringe, they looked like playground bullies.

“She needs to give me money,” one said. Soon after, presumably concerned that a police arrival was imminent, they left.

Police officers came, took notes, and when I pressed them about how they were going to investigate the case and what protection we could expect, they sort of shrugged and said “It’s a debt collection issue.”

Reports of arson and false imprisonment are among them and that count doesn’t include the number of debt-related aggressive behaviour that either the authorities don’t believe warrant recording, or the attacks that go unreported altogether.

“They say bad words to me and they call me day and night,” said one Filipino domestic helper I spoke to who was being harangued by loan sharks when she fell into debt. Her employer had gone with her to the police station to make a report, but were effectively turned away.

“They were saying intimidating things like ‘We know where you live’ but the police officer saw that as insignificant. “Of course they know where you live,” he had said.” A threat is only considered a threat if it’s explicit. Psychological warfare tactics tend to go under their radar.

Employers can also become embroiled in the debt issues of their employees. Some have had their cars scratched and many have received violent threats over the phone.

NGOs I spoke to when researching where Maria and her family could get help said that the ballooning number of dodgy creditors targeting the city’s neediest were hard to clamp down on and even harder to track.

The underground industry has been mushrooming since the 80s and 90s, she added, fueled by the rising number of imported, incredibly cheap live-in workers whose social standing as 2nd class citizens make them easy targets.

Proposals to ramp up laws against aggressive loan shark activity were overturned and deemed unnecessary.

Unfortunately, the law provides scant protection. Proposals to ramp up laws against aggressive loan shark activity—including an extensive law commission review, and efforts to introduce an anti-stalking bill with a clause related to debt collection—were overturned and deemed unnecessary.

Domestic helpers and migrant workers from South East Asia are particularly vulnerable targets to loan sharking owing to their insecure two-year visa status here alongside their extremely low salaries. The threat of having their visa revoked can act as a strong deterrent to filing complaints about unlawful loan agreements.

And many are already in debt when they first arrive, having been offered complicated “fly now, pay later,” schemes as well as exorbitant and illegal “training” fees that they have to pay the employment agencies. Once they start to miss payments, their agencies link them up with the loan sharks that would come to make their lives hell.

—

Maria* moved out for a month or so, leaving behind her parents with her baby, and we had no more late night visits. She never told me how she had got into all that debt and our metal gate never got fixed. For the most part, our landlord remained uninterested by the petty dramas of his tenants.

As for me, I moved out some time later to a place with windows and a door with a solid lock.

*Maria’s name has been changed