In the heart of the CBD where business folks commute in the midday sun, a familiar face walks around collecting discarded cardboard or old furniture. His lorry is parked near cafes that serve coffee priced at more than five dollars a cup, a luxury he will probably never afford in his lifetime. In the meantime, while every security expert seems to be looking into the abyss of cyberspace for the next big phishing attack or security breach, this old rag and bone man, more locally known as the ‘karanguni’, could be holding one of the keys to solving some of the data breaches that have been plaguing our nation.

If you’re thinking there’s nothing anyone can really do with just your NRIC number, read this article that was just published in relation to the Singhealth data breach: ‘Hackers searched for PM’s records using his NRIC number’.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Everyday on the news, you’ll come across stories of some data breach that occurred in Singapore or overseas. Yet not all of these breaches are linked to cyberattacks. (Read about the biggest physical data breaches in 2016 here.)

According to a report that was published in The Straits Times two years ago, unshredded paper documents from UOB bank were found around the Boat Quay area. Contained in them was confidential customer data such as “corporate statements, loan applications, and internal reports from the bank”.

In summary, UOB said in its statement that they ‘concluded their investigation on the matter’. How convenient.

While it’s been two years since UOB and the other banks apparently cleaned up their acts, I decided to take a walk around the CBD anyway to see if I could find any more occurrences of unshredded paper documents containing private information. And I wasn’t disappointed.

The places I poked around were the alleys around 6 Battery Road, Market Street, D’Almeida Street, and Amoy Street, around the same location where the bag of private UOB documents were found.

For this prized possession? Sure, why not.

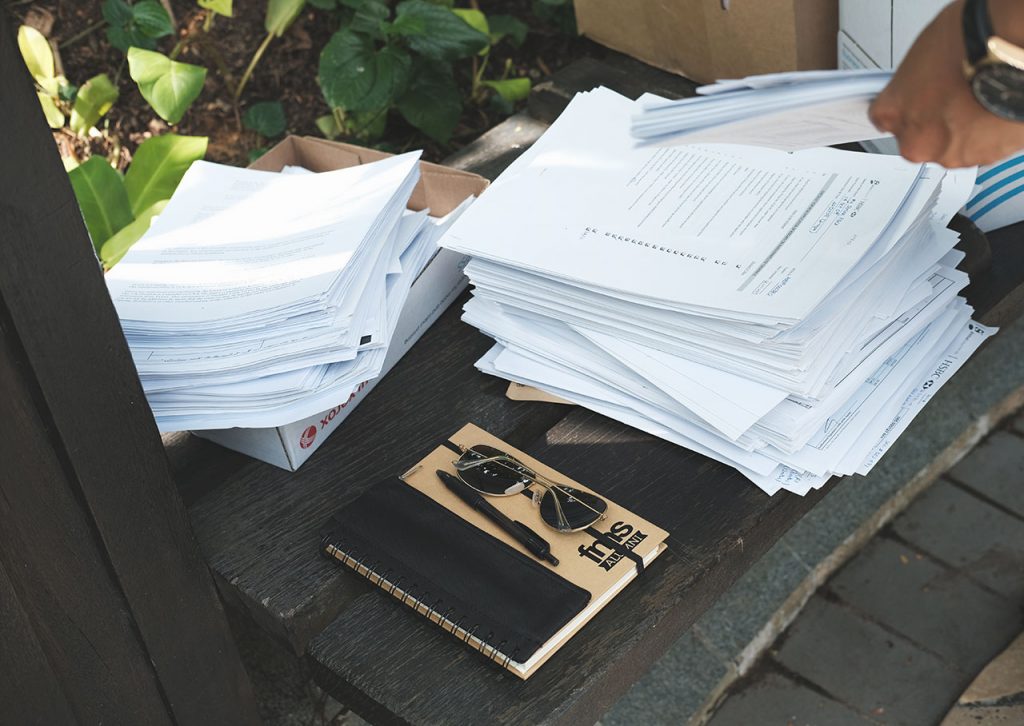

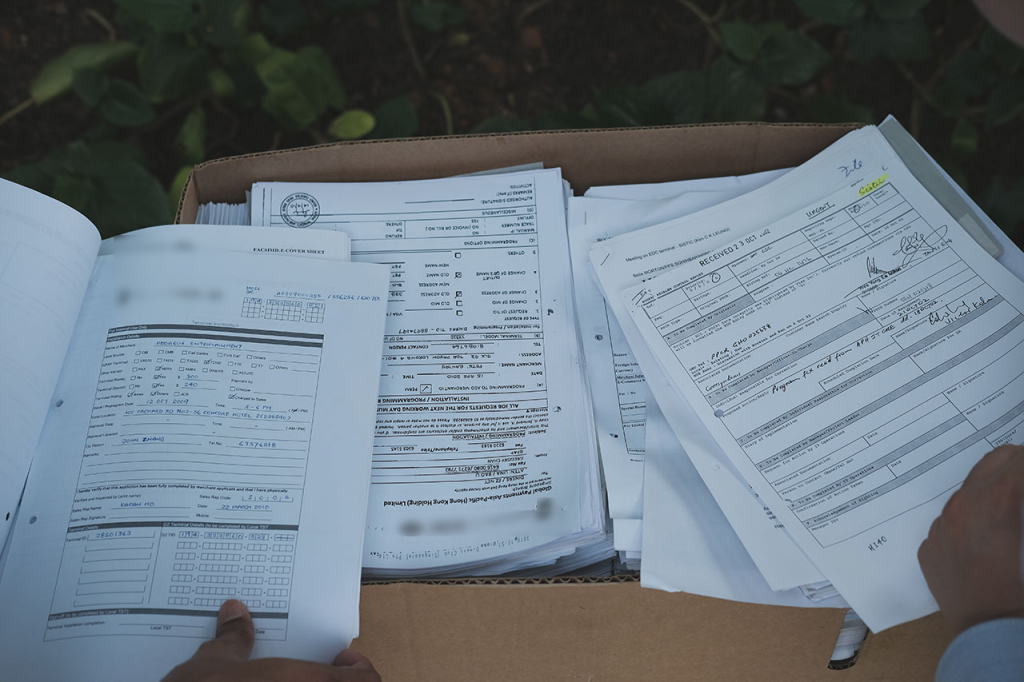

As I sieved through some of the random boxes at the top, I saw documents such as emails, number lists, and order forms with particulars that caught my attention right away. I took a few stacks of paper which weighed around 3kg in total, for which I paid $13.50, around $4.50 a kg. Giving the uncle $15, I told him to keep the change, which made him a happy camper.

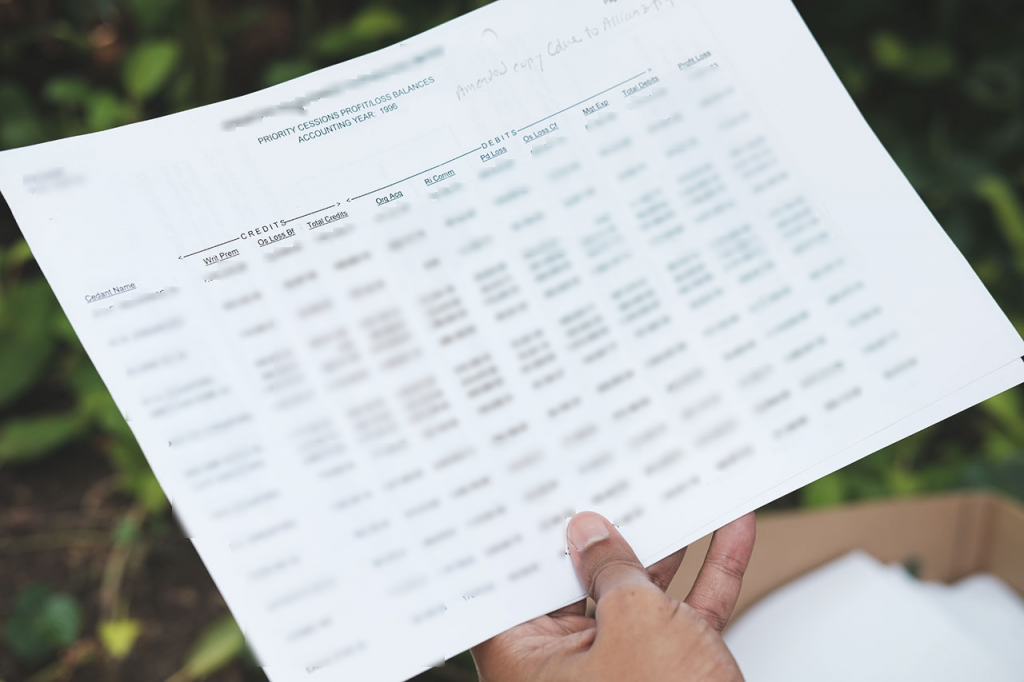

Later, I found that there were many documents containing familiar bank logos with customer details and addresses. There was even a profit & loss statement from a company with a detailed breakdown of all their expenditures—something a competitor would pay good money for (see image below). In the wrong hands, personal data with this information could result in reputational damage to the individual concerned, identity theft, or, in extreme cases, possible terrorist related activities on which I will elaborate later.

It also made me wonder: how much more data could I have easily retrieved from the truckload of unshredded paper which was just a day’s worth of takings?

Mr Tan recounted that many large companies do not shred their private documents but instead drop them in unsecured recycling bins in the office, which “can be easily accessed by anyone”. At the end of the day, these papers are then sold directly to karangunis or taken by the ‘cleaning aunties’ to be sorted and then sold to the karangunis. The reason these documents are left unshredded, according to Mr Tan, is so they can fetch a higher price when sold to karangunis.

I also spoke to Mr Tan about what I noticed around the CBD, which I labelled a ‘Rag & Bone Network’ consisting of ‘sorters’ and ‘transporters’.

The ‘sorters’ usually consist of cleaning aunties who take the bulk of unshredded paper from the offices to sort, while the ‘transporters’ are the ones who collect these sorted documents from a designated location in the CBD to be sold elsewhere. Mr Tan then added that this unshredded paper is usually sold to recycling companies, after which they are sent to paper mills in the Asia-Pacific region.

It is through this process that private documents are at the mercy of ‘data mongers’ who gather private information through dumpster diving for their own sinister purposes.

In a recent case this year, the PDPC (Personal Data Protection Council) fined a former telemarketer S$6000 for dealing with other peoples’ personal data, which included NRICs and telephone numbers. According to the article in the Straits Times, the telemarketer bought these leads at around 30 cents each, containing ‘NRIC numbers, mobile numbers and annual income ranges’ from ‘unknown sellers’.

I know what you’re thinking. This sounds like some half assed conspiracy theory from a Dan Brown novel. Unfortunately, it’s not.

“Since organizations are getting better at protecting their digital information through encryption, passwords, firewalls and network monitoring, it is easier for criminals or terrorists to go after physical data such as paper documents containing confidential and/or personal information,” said Mr Peretz.

“It is also more challenging to trace the source of a leak with physical breaches, which sometimes allows them to get away before a breach is detected.”

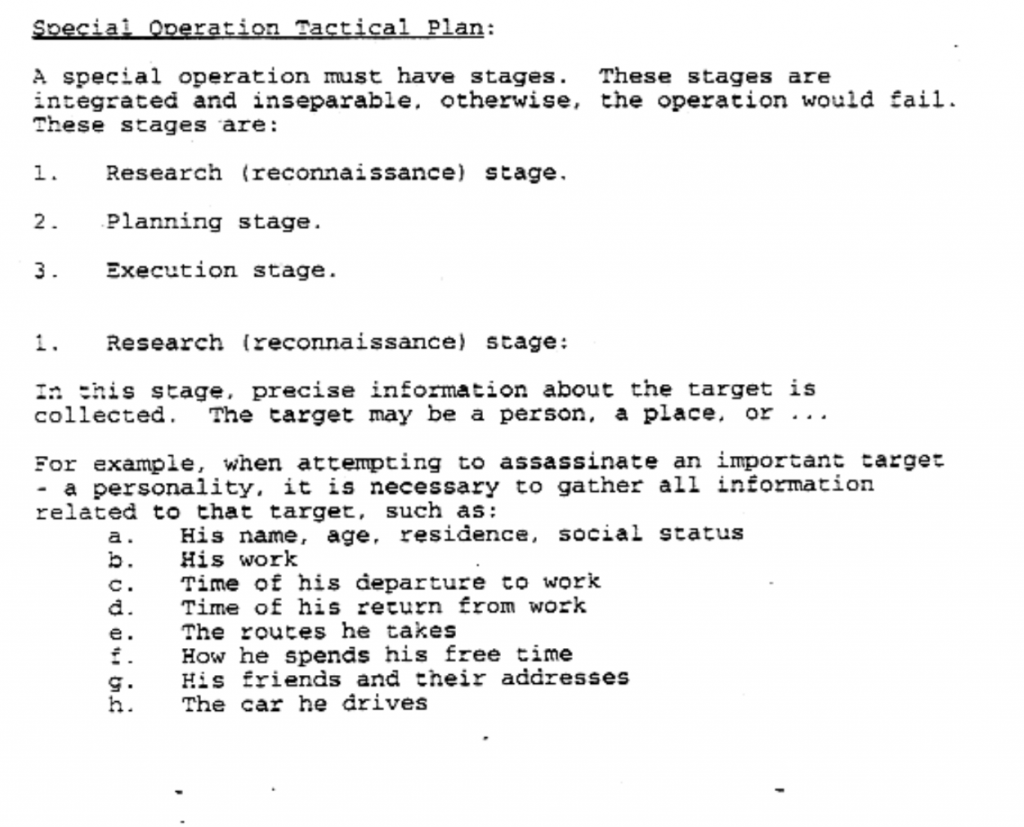

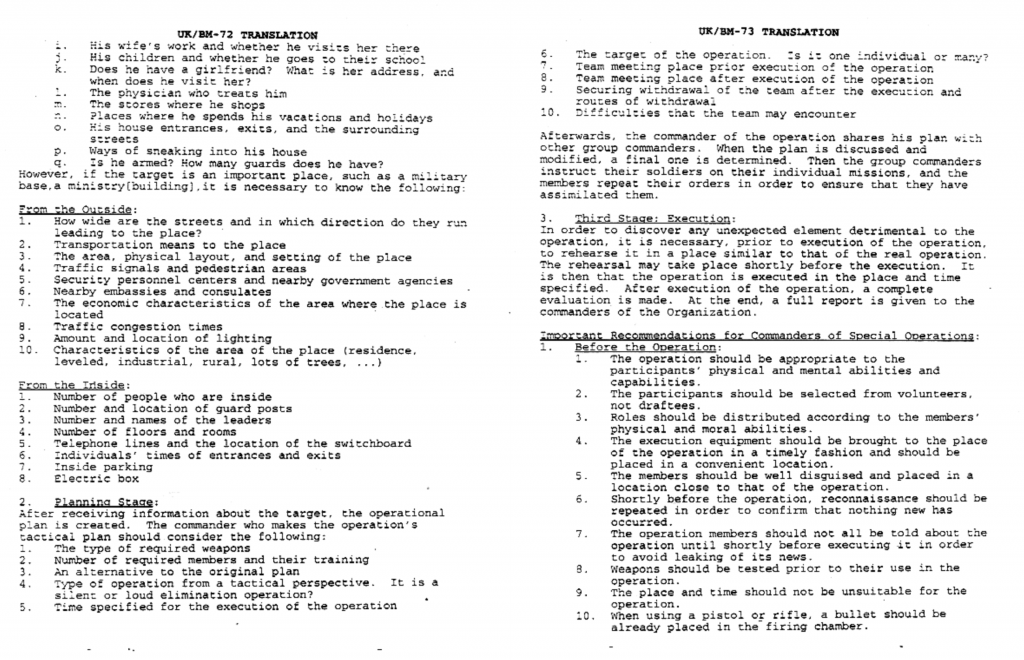

According to pages 73 to 75 (please see images below) of an Al Qaeda manual found in Manchester that was translated by the authorities, the three steps in a ‘Special Operations Tactical Plan’ are the ‘Research stage, the Planning stage and the Execution stage.’

At the research stage, the terrorist has to get as much detailed information of his/her target as possible, such as “how he spends his free time; his children and whether he goes to their school”; even “how wide are the streets and in which direction do they run leading up to the place”.

Apart from using social media like Facebook to gather this information, Mr Peretz mentions that going through a person’s thrash is also a ‘no brainer’ method to obtain useful information from credit card statements and personal emails that are printed. Even takeout delivery order statements show the precise times when a target would be home.

However, more needs to be done in this country to educate citizens about the dangers of sharing private data in whatever form compared to just eating into their wallets. In many developed countries in Europe and the UK, attitudes towards sharing personal information have always been conservative, compared to Singapore where anyone is usually willing to disclose their NRIC details just to take part in a lucky draw.

And while it is important to have effective cybersecurity measures in place to prevent a breach, let’s not forget that even with SingHealth’s state of the art intranet system, it was still compromised.

We must also be mindful that it’s easier in many cases to gather personal data through low-tech methods like dumpster diving, photocopying your NRIC, or going through a stack of wrongly printed emails.

Let’s hope the recent data breaches will be a wake up call for anyone who doesn’t want their private information to end up in Nigeria or worse, the dark web.