Imagine this:

You are fifteen years old. Your biggest concern is whether you will complete your revision on time so that you can paint on the weekend. You just received news that you have been awarded a scholarship to study in another country. You have one day to decide whether you want to accept the offer.

Sounds familiar?

Probably not.

But this is what Rebecca, and many other foreign scholars in Singapore, went through. Rebecca is from Hunan, China, a province known for its love of spicy food. She loves painting, so much so that she took H2 Art. She is a Life Science and Psychology major who spends her free time bouldering and watching dramas.

“My favourite place is my bed,” she laughs.

Singaporeans are no stranger to foreigners, nor are we unfamiliar with foreign scholars. I remember Chinese scholars gathering in secondary school hallways, their grades good enough that they were always streamed into the best classes.

What I don’t remember is talking much with any of them.

I sat down with Rebecca, Jenny, and a few other scholars who had come in through the SM1 programme to find out what it was like to be a foreign student in Singapore.

What was it like to move to another country at fifteen years old? What’s it like now, almost a decade later?

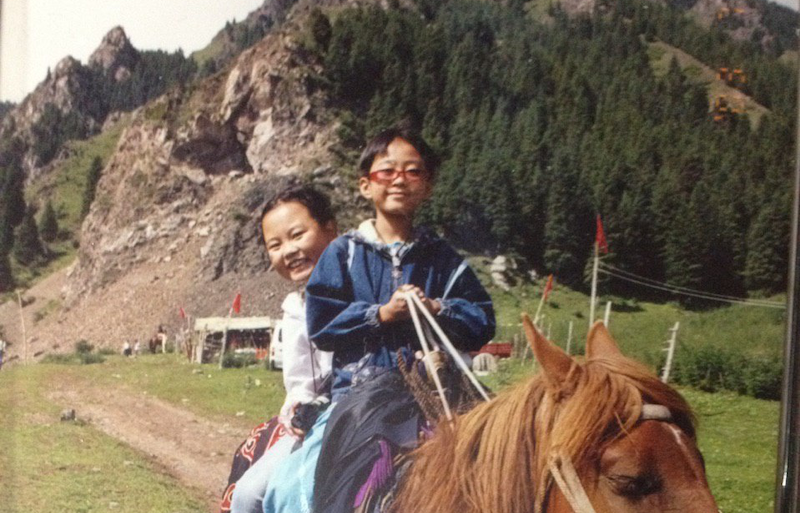

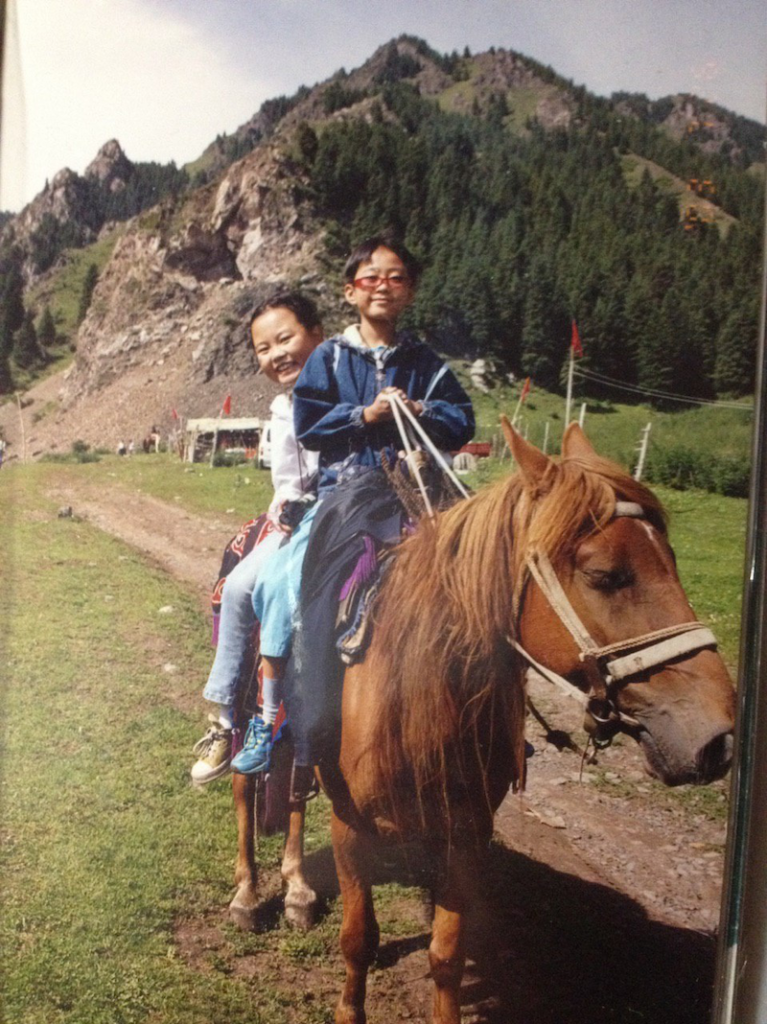

“The moment we stepped into Changi Airport, I thought to myself: so humid!” Jenny exclaims. Urumqi, a city in the province of Xinjiang, is dry even in the summer.

“When I came here, I saw people wearing FBTs and they were so short. Now I’m used to them. It’s very comfortable.”

“My English was P4 standard.”

The language barrier didn’t just mean she had to relearn everything in a new language—it was also a social barrier. The Singaporean accent was unfamiliar, and took her a while to pick up.

“Learning Singlish helped me adapt and become more Singaporean.”

To prepare for the O’ Levels, Lionel wrote an essay every day for a month. He even rewrote one particular essay eight times. English wasn’t the only language barrier, either. To my surprise, he said that he also faced issues with Mandarin.

“The northerners would make fun of my Chinese,” Lionel laughs. He comes from Shantou, located in the southern province of Guangdong, and his first language is Teochew.

“I would speak Teochew with the auntie in JC and she gave me a lot of noodles.”

Everyone’s eyes lit up when asked about food. While it was easier to adapt for some—like Lionel, who was already used to southern Chinese cuisine—it was a more drastic change for others.

“Xinjiang food has a lot of beef and mutton,” Jenny says. Singapore food is a lot lighter and soupier. She is used to it now, and smiles when she declares that her favourite dish is sliced fish noodle soup.

Living alone abroad, she says, requires a lot of self-discipline.

“My friend’s teacher asked for someone to be the class monitor,” she says.

“My friend raised her hand, but the teacher kept asking for more volunteers, until a local student raised her hand, and they picked her instead. Then, in the toilet, she heard them laughing about why she’d raised her hand and saying stuff like, ‘who does she think she is?’”

These experiences of othering were common. While some found it easier to integrate, others faced more difficulties.

“I would speak in English, and I didn’t know whether people were pretending not to understand so that they didn’t have to talk to me,” Jenny says.

For the scholars, just like anyone else, their social circles transformed as they grew older. They might have started with more Chinese friends—scholars that stuck together because of similarities in a foreign land—but they all gradually met more locals.

“Now, most of my friends are from [my residential college],” Rachel quips.

When we sat down to talk, Rachel had just commemorated her eighth year in Singapore by celebrating with her hostel mates from secondary school. Some were no longer studying here, but they all met up over Skype.

Like the others, Rachel has spent her schooling years since Secondary Three in dorms. Living alone abroad, she says, requires a lot of self-discipline, something that the others concurred with. They had a guardian who oversaw them, but it was never the same as having a mother or father around.

“When I told my mother I wanted to go to Singapore to study, she stopped the car on the side of the road and cried.”

The other scholars I talked with, however, had starkly different experiences. Most were encouraged or even “forced”, as Jenny describes, by their parents to study overseas. The scholarship was something prestigious, only offered to top students.

In the end, Rachel’s mother became supportive, even helping her find scholarships. Rachel is from Shantou, like Lionel, and has relatives here. When she first arrived, they showed her around—to the Night Safari, to USS—and she spends every Chinese New Year at their home.

The thought of living alone overseas wasn’t terrifying for her. Rachel wanted to see the world.

Chris also wanted to see the world, but he was worried about being away from home. In fact, he cried during the scholarship interview.

“I was surprised I got accepted,” he laughs. “My interview was fifty minutes long.”

“I was walking along ECP at night with a friend, and we looked at the moon and talked about home and cried together,” Melissa shares.

For Rebecca, the first time she felt homesick was after her first trip back to China. She was making her own bed and thought to herself: if she was at home, she wouldn’t be doing this.

Rebecca describes a scene she painted in junior college: a girl sleeping on a bed, two suitcases on the ground, and a hand knocking on the door. Its name—Do you still like eggplant?

“I used to like eggplant,” she tears up as she says this. It’s barely noticeable except for the shine of her eyes.

“I went home, and my mum wanted to cook something for me, but she wasn’t sure whether I liked eggplant anymore.”

“I’m open to possibilities,” Melissa says, happy to move back to China or to stay in Singapore.

“I really like the environment here. When I came back from exchange, it was like coming home.”

Jenny seriously thought about settling down here—she’d talked about getting a BTO with her ex-boyfriend. Rachel has even thought about which school she wants to send her children to.

Chris intends to do a PhD. Where exactly he’ll go after that, he says, is a bit unclear. For Rebecca and her girlfriend, the future is uncertain as well: same-sex marriage is illegal in both Singapore and China.

Being abroad means that they’ve seen things from different perspectives and have been immersed in different cultures. When I talked to them, I realised this: their stories and insights have been very much influenced by their diverse experiences. What ties all of them together is their open-mindedness and maturity, which has come from learning to live independently and adapt.

Even for the scholars themselves, they’ve rarely had the chance to sit down and reflect on their past eight or nine years in Singapore. Each person has their own story to share; to be honest, I doubt that a single interview is enough to encompass the true breadth of anyone’s experiences.

“There’s a lot of heterogeneity amongst Chinese scholars,” Rebecca affirms.

Everyone has their own narrative. Even if they are tied together by a common thread of being Chinese scholars in Singapore, it doesn’t mean that everyone can be described using a single adjective.

Incidents like these are not uncommon. They reflect the general sentiments that Singaporeans have towards foreign scholars, migrant workers, and immigrants in general.

In August 2019, Education Minister Ong Ye Kung responded to a question in Parliament on the amount of spending on foreign students. He argued that even if foreign scholars do leave Singapore after serving their bond, they “can be part of our valuable global network of fans and friends, who can speak up for Singapore, and forge collaborations with Singapore”.

Minister Ong’s words are echoed in Melissa’s feelings towards Singapore.

“I do not tolerate people saying anything bad about Singapore as well,” Melissa says, when asked about her thoughts on living abroad.

Yet, despite years of espousing the narrative that foreigners benefit Singaporeans both economically and socially, Singaporeans don’t seem to be entirely convinced. A quick look at the comments section of MOE’s Facebook post is all you need to grasp the extent of discontent and cynicism surrounding the government’s stance on foreign scholars.

The effects having foreign scholars in our midst, whether positive or negative, go beyond just taking up one percent of our education budget.

The issue of foreigners in Singapore society is not just a matter of numbers. Every person in Singapore, local or foreigner, is inevitably weaved into the social fabric of the country.

When considering our perspective towards foreigners, merely citing dollars and percentages is not enough. Not only do we have to understand the possible social effects, we should also understand the viewpoints of different stakeholders: Singapore citizens, the government, and the foreigners themselves.

Even if we see their presence here as temporary, a temporary presence is still a presence after all, and denotes a unique individual that has the potential to impact the lives around them. Taking the time to sit down with a foreign scholar—or a migrant worker, or a new immigrant—might just be what we need to grant ourselves a little more empathy and perspective.