Top image:: Priscilla du Preez//Unsplash

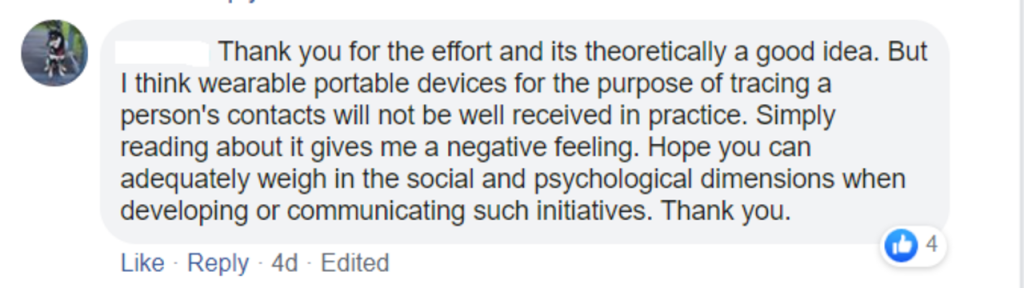

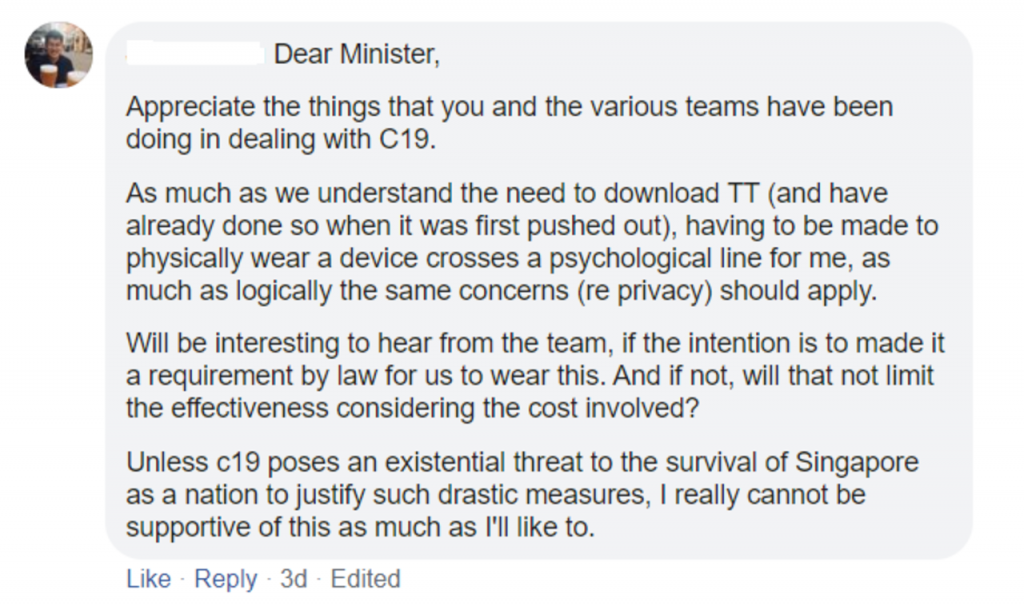

The government’s recent announcement that it will be rolling out wearable TraceTogether tokens has sparked furious debate and opposition. At the time of writing, a petition against the tokens has already gathered over 42,000 signatures, with many Singaporeans expressing discomfort towards the token and the implications of introducing it.

RICE spoke with Mr Roland Turner, a data privacy professional, to unpack some of our fears around the token, and whether we should indeed be proceeding with caution.

Roland is Chief Privacy Officer at TrustSphere, where he is responsible for the company’s information policy and practices. He is a HackerspaceSG founding member and FOSSASIA organiser, and an executive committee member of the Internet Society of Singapore.

Sophie: Let’s start with the tech side of things. Could you briefly explain how TraceTogether works?

Roland: The protocol that’s used is called BlueTrace. This was developed by a team in Govtech, and I have to say that it’s a very clever way of solving several problems simultaneously: identifying close physical contacts, controlling battery use, and avoiding the sort of location tracking that might seem like the obvious starting point.

When you encounter another phone with the app, TraceTogether generates a new random identifier that changes periodically. So even if someone tries to sniff through the data, they still can’t use it, because who you were, say, 15 minutes ago and who you are now looks like two different identities. That’s the first major thing TraceTogether solves.

Only MOH contact tracing officers have access to the database required to piece the identifiers together. To minimise the risk of abuse by someone in government, or by a successful intruder, that database does not include the complete set of recorded contacts for the entire population, only for the smaller number who have been diagnosed with Covid-19.

What BlueTrace allows is for the recorded information to not enter a central database. It broadcasts the randomised identifiers, which stay just on your phone or the token, and remembers it for 25 days. If and only if you are diagnosed as Covid+, then you have to turn it over because you are obligated to participate in the contact tracing process.

On the information we do have available, the token should do the same thing as the app, with some differences of necessity.

How would the authorities then use the data from the token to contact other people? Would the token still have to be linked to you by a unique identifier, like your NRIC number?

I mentioned that there are some necessary differences between the app and the token, and there’re two that I can see.

One is the updating of the randomised identifiers. The app contacts the MOH servers every 24 hours to generate a new set of identifiers, and the token can’t do that. We don’t yet have public details of how; cryptographically there are a few ways this can be done.

Both the app and the token need to be associated with a person. Without that, they’re useless. But the second difference is that method of association with the token will be different, in part because the token has to be useful even if the person doesn’t have a smartphone.

What are the risks associated with this?

Neither of these presents a major risk over and above the use of the app.

The broader risks remain the abuse of the system for purposes other than Covid-19 contact tracing, whether by a malicious actor within government, or by an outside attacker. The various features of the system that resist these abuses operate the same way for the app and for the token. These include the new random identifier every 15 minutes, the limited retention of data in the app and the token, and limiting access by the contact tracing team to the recorded contacts of positive cases.

Location tracking has been one majorly cited fear, despite all the assurances that TraceTogether does not track locations. Does no GPS and no data connectivity mean our locations cannot be tracked?

‘Cannot’ is a very high standard, and is not usually important in data protection discussions. More importantly, it is impractical to use TraceTogether as a tracking system.

It would be possible in principle to deploy a network of BlueTrace protocol devices at known locations. Each would have something like the token to perform BlueTrace communication, perhaps a small solar panel for power, and perhaps a mobile network module to allow it to report detections continually to a tracking system. TraceTogether apps and tokens would exchange information with these as usual, and the tracking system would therefore be able to determine from minute to minute where every device using TraceTogether was located, and therefore every person carrying a BlueTrace device.

Setting aside the enormous expense and high visibility of such a rollout (tens of thousands of devices would be required), networks with this capability already exist and are already able to provide tracking information for all mobile phones, not just smartphones: the devices are mobile phone towers and the networks are the 3G/4G mobile phone networks. Criminal investigators and courts are already able to use these networks for tracking suspects in serious cases.

To build a parallel network at greater expense (because of the larger number of locations required) to achieve what’s already possible with the existing networks makes no sense, and therefore isn’t a realistic threat.

No equivalent threat exists from non-government actors, because even a huge network of BlueTrace devices is useless for tracking without the database of registration information.

So is the furore over the tokens justified, from a data privacy standpoint?

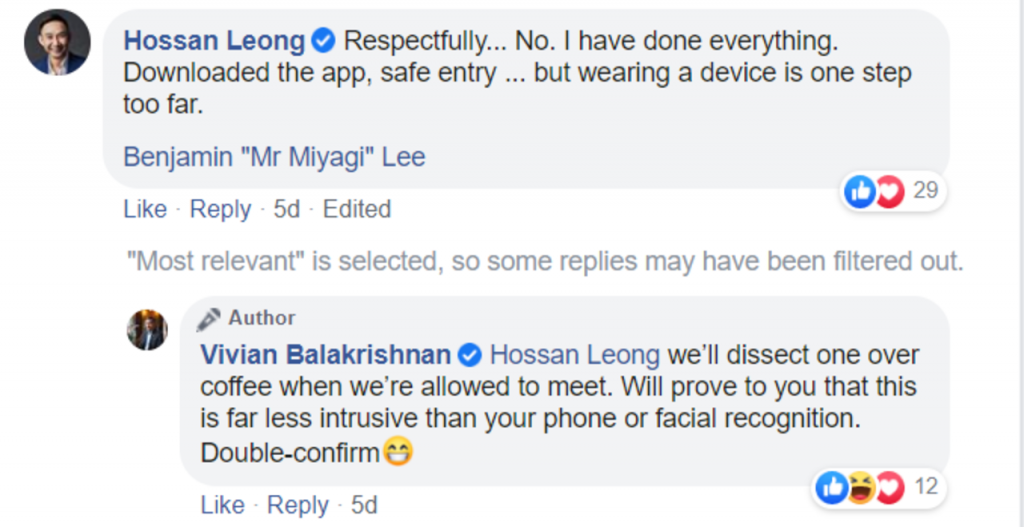

It’s not obvious to me that the token deserves more pushback than the app on data privacy grounds.

In my opinion, it’s that three things happened together [which led to so much resistance]: mentioning that the app was not made mandatory because of its problems with iOS, the addition of the NRIC, and the token, which extinguishes all the reasons why people can’t use the app.

When Minister Balakrishnan said that they hadn’t made it mandatory because it doesn’t work well across all phones, I hope he was simplifying, and the iOS reason was not the primary one for not mandating it.

Do you think the 75% takeup target can be hit without making TraceTogether mandatory?

I’m not sure it’s helpful to speculate, but I guess I’d say that 75% is a little arbitrary—there is no point at which it goes from being ‘not good’ to ‘good’. You just get better as you go.

The importance of 75% is that it’s the point at which more transmissions are detected by the app than aren’t. Beyond that point, it’s a Pareto principle problem. After a while, you hit diminishing returns.

The risk of putting it this way is that it makes it sound like if we don’t hit 75%, it’s useless, and that’s not true. Even with the currently low takeup rate, it’s already delivering value. We don’t know how much, but it’s clear that this helps with jogging the patient’s memory.

Failure to achieve 75% is not a failure overall, so don’t confuse the end point that the government is shooting for with the success criteria, ie: as much as possible, or where beyond that it’s not worth expending more effort.

But I do think mandating TraceTogether would be a terrible idea, even with the extraordinary times we’re in. Getting the entire population to use contact tracing devices is straight-up freaky, for one; it would generate lots of distrust, anger, and resentment. And even if you were to make it a mandate with exceptions, there are very real problems with that.

So in your opinion, are the reassurances we’ve been given satisfactory? What other safeguards would be appropriate?

Broadly, yes, I think they’re okay. I guess there are two questions here: whether TraceTogether is a good idea, and what additional things are appropriate. It’s the latter which I feel has some gaps.

You might be aware that a review of the PDPA is imminent. One of the big things there is accountability improvements: if a private sector organisation wishes to process data, it will have to perform and document a balancing exercise—a due diligence type process where you identify the risks, the appropriate protective measures, the residual risks, all before you go ahead. The idea is that whatever benefit is being pursued must warrant the risks being taken.

In my opinion, what was missed with TraceTogether, first of all, is that this impact assessment was not published. For example, in Australia, OpenTrace was picked up, but they’re bound by a slightly more developed privacy regime, so they both performed and published this impact assessment.

I do accept the assurances being made, and given the diligence that I’ve seen in Singapore in dealing with information security, I think it’s reasonable to assume this is being handled well. But right now, we have some data points, some explicit, some speculative, but fundamentally we’re having to guess.

Publishing the assessment, and in particular what processing is being performed, would help us answer a lot of questions. It would allow specialists and civil society to review the information, and not just grab onto whatever small fragments have been released by government ministers. Even if some info has to be redacted for safety reasons, it would still be desirable.

The second thing is that the government should facilitate independent review of the software embedded in the tokens. This is a highly specialist area, but there are a number of people in Singapore who are able to do so.

This requires that two things be done. One, the source code be published, as was the case for TraceTogether or OpenTrace. Two, the hardware manufactured without some of the usual measures to prevent non-destructive examination (to get access to the chip without destroying it). Were the government to include this in its requirements, the comfort factor of having independent experts who have examined it would likely calm the public discourse somewhat.

A transparent approach increases the likelihood that when the dust settles, more people will have understood what is going on, and trust it. This is hugely important to retaining trust in government. It’s not adversarial; it’s about transparency.

Are we misguided in getting up in arms over the token when we already cede a lot of our privacy to both tech companies and the state?

The data that companies like Facebook and Google have—which they can use to benefit anyone willing to pay, based on the quite detailed profiles of users which they have—is not compatible with democracy. You can’t have an informed populace seeking and gaining and sharing info if the most powerful player is selling control of what’s shared to the highest bidder. It’s a real threat.

With regard to contact tracing, it’s hard to point to a serious risk of harm based on what has been done so far, what is proposed, and the likely trajectory. Nonetheless, a lack of diligence risks allowing this to slide and grow in scope.

If everything goes well and we get a vaccine before Christmas, that’s great. It’s short term. But if we’re stuck with this for ten years, then all the other changes to society and systems and protections will evolve around what we’ve got.

That is the risk. It’s not about yes/no to what is being proposed today. It’s a failure to remain diligent for the duration of this thing, such that when the risk is low enough that the measures can be removed, we will forget to remove them.

Are you Team App, Team Token, or Team Not-At-All? Let us know at community@ricemedia.co.