“Huh? SAP school? Oh, you mean Chinese schools lah.”

The fact that these two terms can be used interchangeably in local vocabulary speaks volumes.

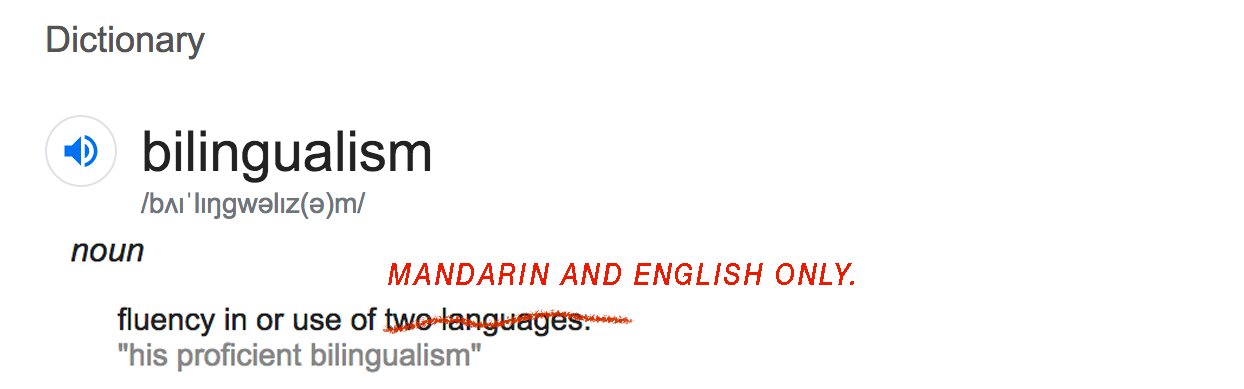

For those who are unfamiliar, Special Assistance Plan (SAP) schools are public primary and secondary schools in Singapore that are specially catered towards developing “effectively bilingual students” that are “inculcated with traditional Chinese values”.

They are, by nature, exclusive to Mandarin speakers; inevitably, most SAP schools are distinctly racially homogeneous.

SAP schools are also undeniably amongst the elite institutions in Singapore. Although not all elite institutions in Singapore are SAP schools (RI and ACSI are prominent examples), the added resources and opportunities that SAP schools have are difficult to ignore.

For instance, they boast higher funding per average student, and many of them offer the coveted Integrated Programme pathway. So it’s easy to see why SAP schools are considered highly desirable by students and parents alike, though not necessarily because of their strong emphasis on Chinese culture.

The government’s concerted cultivation of SAP schools, coupled with the fact that they are essentially ethnically-exclusive, has received much criticism in recent years. Many assert that SAP schools only serve to further the racial divide and further entrench Chinese privilege in Singapore.

This debate is by no means new, and for the sake of not rehashing old arguments, let us accept the following premises:

1. There is an inherent value in preserving and actively appreciating the Chinese culture.

2. Learning Mandarin has very tangible benefits, especially in terms of improving our economic and political position with powerhouse China.

However, amidst sharing from alumni and comments from various prominent public figures about the value of SAP schools in today’s education system, one important perspective has been largely neglected: the ramifications of the SAP system on the very people it excludes—the non-Chinese minority.

As an outsider looking in, Shaf* has several conflicting feelings about the issue. Though not from a SAP school herself, Shaf graduated from a prominent elite institution in Singapore. It was in junior college when she first truly interacted with other students who came from predominantly Chinese school backgrounds, such as CHIJ Saint Nicholas Girls’ School and National Junior College. (The latter isn’t a SAP school.)

Before diving into some of the rather unsavoury conversations she’s had, she prefaces them: “I want to stress that this is not all of [the people I’ve met], but some of them really don’t seem to know anything at all about non-Chinese culture.”

“They’ve said things to me like, “I can’t differentiate between Malay and Indian”. Sometimes some of them get very confused when they realise I’m Indian-Muslim, and ask me questions like, “How are you Indian if you’re Muslim?”

Once, I was even asked if water was halal.

Preethi, a student who graduated from Hwa Chong Junior College seven years ago, shares that despite the positive experiences from Chinese school students of a minority race in a Straits Times article, her experience was far from sunshine and rainbows.

She says, “Going into Hwa Chong, I was made so aware of the fact that I am a minority. It was also the first time I really experienced classism and racism.”

Sharing her struggles with tokenism, she described how the school would specifically call for her during photoshoots (presumably for minority representation) and how some of her friends confessed that she was their “first Indian friend”.

Consequently, she felt like she was representing her entire ethnic group especially for those whom she was the first Indian friend to and fielding questions from. Though not ill-intentioned, these were just some of the things that made her feel like the school was an incongruous environment for her.

Neither do I intend to merely lambast Chinese school students for their lack of EQ; actually, none of the interviewees held these comments against the individuals who made them.

What is problematic is that these remarks reflect a disturbing lack of exposure and sensitisation in the youth of today, and this should be very alarming especially in the context of a (supposedly) diverse and cosmopolitan nation like Singapore.

Shaf admits, “I personally don’t think it is really that bad to not know about other cultures. But it’s just the idea that these cultures don’t even seem to exist on the periphery of their vision [which concerns me].”

Preethi adds, “It’s very alarming. If a seven-year-old says something like that, maybe it’s because they are being exposed to different races for the first time in primary school. That seems normal to me. But these comments are made by 17-,18-year-olds!”

It seems like Singaporean children [who go through the Chinese-school system] progress at a much slower rate in terms of being socially and culturally sensitised.

I understand that some SAP schools have been trying to introduce other initiatives to remind their students that other cultures exist, but usually they manifest in ways that are too superficial to be actually helpful. The joint activities and exchanges with Malay and Indian cultural groups as well as students from non-SAP schools are often too sparse and fleeting to coalesce into meaningful interactions.

The compulsory Malay language classes we took in Secondary Two and the annual celebration of Racial Harmony Day did little to deepen my shallow understanding of other cultures.

In fact, it was only when I started interning at AWARE (Association of Women for Action and Research) where I was first really struck by just how incomplete my education was.

Working with my direct supervisor who was in charge of outreach with the local Muslim community, I was exposed to the myriad of social pressures, expectations and harmful stereotypes that Muslim women experience. I remember feeling shocked—and subsequently ashamed—when I realised just how invisible and foreign their struggles initially seemed to me.

This is really embarrassing to admit, but it was only at the age of 19 when I first truly internalised what it means to have Chinese privilege in Singapore. I really did grow up as one of those culturally-insensitive ‘elites’.

So let’s be realistic here: the average Singaporean student spends most of their time in school. When you segregate children at such a young age (remember, most SAP high schools are affiliated to JCs, and MOE has also introduced SAP primary schools), they spend some of the most formative years of their lives within an artificially homogeneous bubble.

Therefore, while Chinese schools are not the sole cause of the lack of racial mixing in our society, they are a significant contributing factor. We must also acknowledge that an intersection exists between the issue of SAP schools and larger social inequalities like elitism, classism, and racism.

And we must definitely stop throwing around vague statements like “There is room to do better”, which are really more of a gentle admonishment than an actual recognition of the severity of the problem.

When conversing with Shaf, she describes how her sister grappled with choosing a secondary school post-PSLE, realising her choices were limited by the fact that most of the “good schools” she was considering were all SAP schools. This a real life example of how the presence of SAP schools can genuinely limit the opportunities of the non-Mandarin speaking.

And yet, we previously agreed to accept the premise that SAP system has certain inherent benefits, so it can’t exactly be abolished. (Not like that’s likely to happen anyway)

This is a pretty radical suggestion, but hear me out: maybe Chinese schools shouldn’t only be for Chinese students.

Preethi provides an interesting perspective. She says, “If SAP schools are really so important and learning Mandarin yields so many practical benefits, why are we limiting the entry of these schools to ethnic Chinese?”

She believes that many Malay or Indian students would appreciate the opportunity to learn and hone their skills in Mandarin. What better way to do that than to immerse in the rich cultural appreciation that Chinese schools boast?

Shaf shares the sentiment: “Even my immigrant parents understood how important it was, and made sure I took four years of Mandarin under the third language programme.”

Unfortunately, the current education system currently erects an impossibly high barrier of entry for students without any degree of Chinese parentage.

MOE’s website states, “Students are required to offer an official Mother Tongue Language (Chinese, Malay or Tamil) in school. Students of Chinese, Malay and Indian ethnicity offer their respective MTLs”.

According to the MOE helpline, when entering primary school, Singaporean children are automatically assigned their mother tongue based on their ethnicity. If they are of mixed parentage, they can choose between their two mother tongues.

In cases where two Malay parents would like to opt for their child to take, say, Chinese instead of Malay, they would have to fill out a special application and submit it to their child’s primary school, who then forwards it to MOE. All in all, it’s quite a convoluted process, and their application may not even be approved.

In addition, students can only take one mother tongue at the primary school level. Realistically, this means only full-Chinese or mixed students with one Chinese parent are able to gain entry to SAP schools.

I’m sure when the MTL programme was first initiated it probably just made more sense to designate children to their respective mother tongues, since our ethnic communities were still largely segmented. But it’s been several generations since, and I can’t help but wonder if this CMIO classification is too rigid and outdated for our current day society.

Other than opening up the opportunity and lowering the barrier of entry for more non-Chinese students to attend SAP schools, we should also ensure Chinese students are properly sensitised to non-Chinese customs. Though Chinese culture might be the most dominant culture in Singapore, it should not edge out the other cultures.

According to Sangeetha,* a university student who currently stays on campus in a largely Chinese-dominated Residential College, “For minorities, it’s natural for us to pick up on things and be sensitised to the Chinese culture, since the majority of the population is Chinese. But this exposure is typically very one-way.”

When she celebrated Deepavali last year, most people in her college weren’t even aware it was happening (despite it being a major public holiday in Singapore) and questioned why she and another Indian friend were placing mithai or sweets in the common pantry.

“When the segmentation happens at such a young age and it carries through all the way till university, it begins to show when they begin to interact with people outside their own race,” Sangeetha reflects.

To her,

Understanding is fostered through organic interactions, not racial harmony day celebrations.

After all, we are told time and time again to be proud of the richness of our heritage, to preserve tradition, and to celebrate the multi-racial society that we live in today.

It is time we truly buy into this prescribed mantra—and yes, continue to preserve what’s unique about our respective communities—but there’s really no need to sunder ourselves in the process.