Top image: NUS News

Who was George Bogaars?

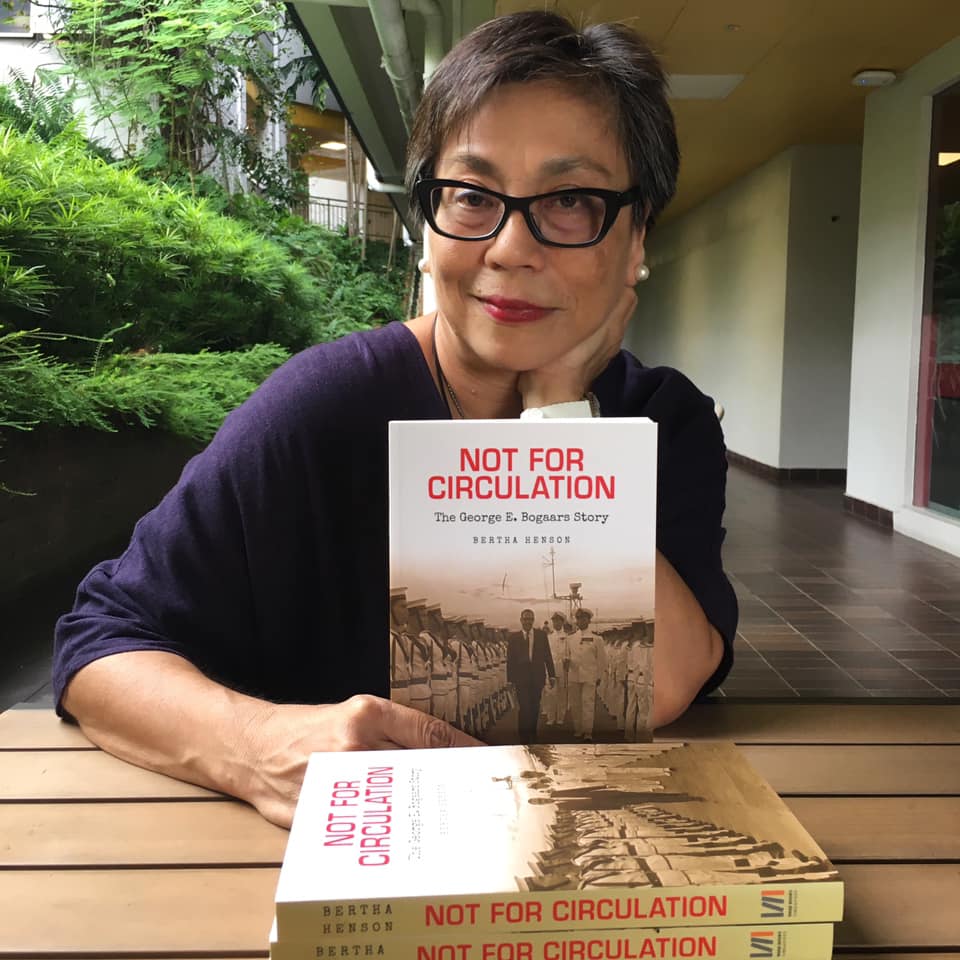

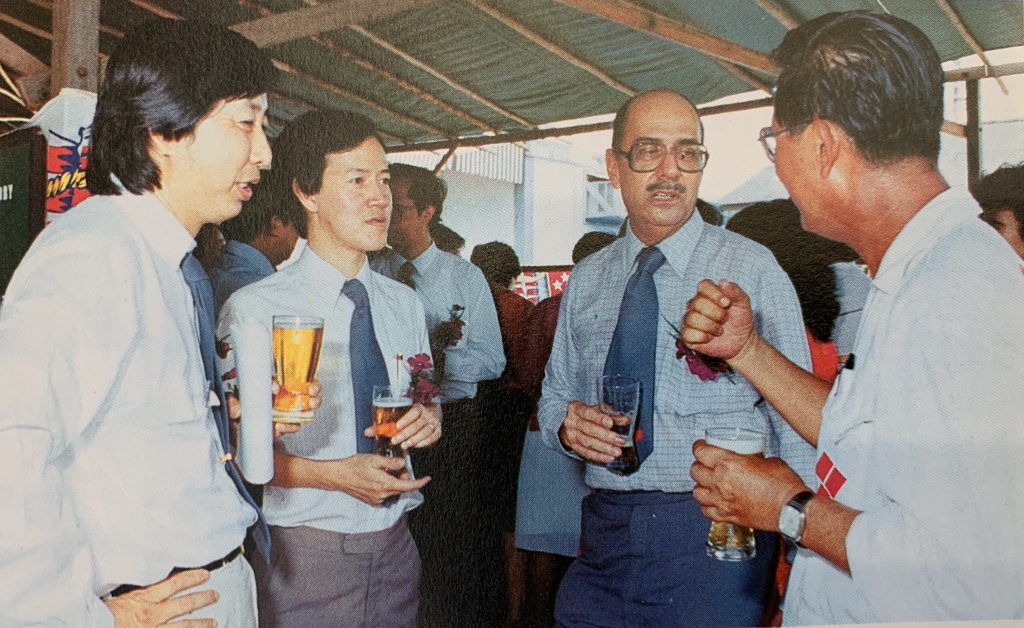

I asked myself this question last December, when university professor Bertha Henson approached me to assist with researching Not For Circulation: The George E. Bogaars Story, a book released on Oct 25 about top civil servant George Bogaars. She was commissioned by his former Finance Ministry colleagues to write this book.

ADVERTISEMENT

I consider myself fairly cognizant in the affairs of local politics. Yet, George Bogaars is a name that evaded me, although, given his contributions, he should be a legendary figure. After all, this man was a spymaster during the most tumultuous era of Singapore’s history, in its journey towards self-rule.

Even Associate Professor Henson, with a vast institutional memory of political figures from her years of journalism, didn’t know much about Bogaars.

There are scant details about him on public record too, a fact I realised as I pored through stacks of memoirs, documents, and newspaper archives. His name is often mentioned in passing—nothing beyond a few lines in someone else’s autobiography.

It didn’t help my research either when Bogaars instructed the National Archives to keep 30 out of the 43 reels of his oral history interviews out of public circulation. According to an email exchange I had with the Archives, he wanted those interviews interpreted in a way he personally approved. Only Bogaars had the sole right to allow the use of his interviews and he kept those rights upon his passing, which meant no usage at all after his death.

I only knew about this written agreement Bogaars had with the Archives when I requested access to the tapes for research. There was a compromise struck, however: I could listen to his interviews but not be allowed to reproduce their content.

Going through his tapes recorded in the 1980s, a casual member of the public could only learn about his wartime experiences but not his time in the public service, probably due to historical and security sensitivities.

ADVERTISEMENT

All I could find online was, after independence, Bogaars also helmed various ministries—Finance, Foreign Affairs, and Defence—as permanent secretary, and oversaw the civil service before retiring in 1981. In the Defence Ministry, for instance, he helped to set up the Singapore Armed Forces Training Institute, or SAFTI.

He was LKY’s right-hand man

When our merger and separation with Malaysia are taught in school, a few household names would be brought up: Lee Kuan Yew (our first prime minister), David Marshall (our first chief minister), and Tunku Abdul Rahman (Malaysia’s first prime minister).

History buffs more interested in a revisionist version of our history might delve into the controversial Operation Coldstore of February 1963. Key figures such as Lim Chin Siong, Fong Swee Suan, Poh Soo Kai, and James Puthucheary—all of whom were detainees—would be mentioned.

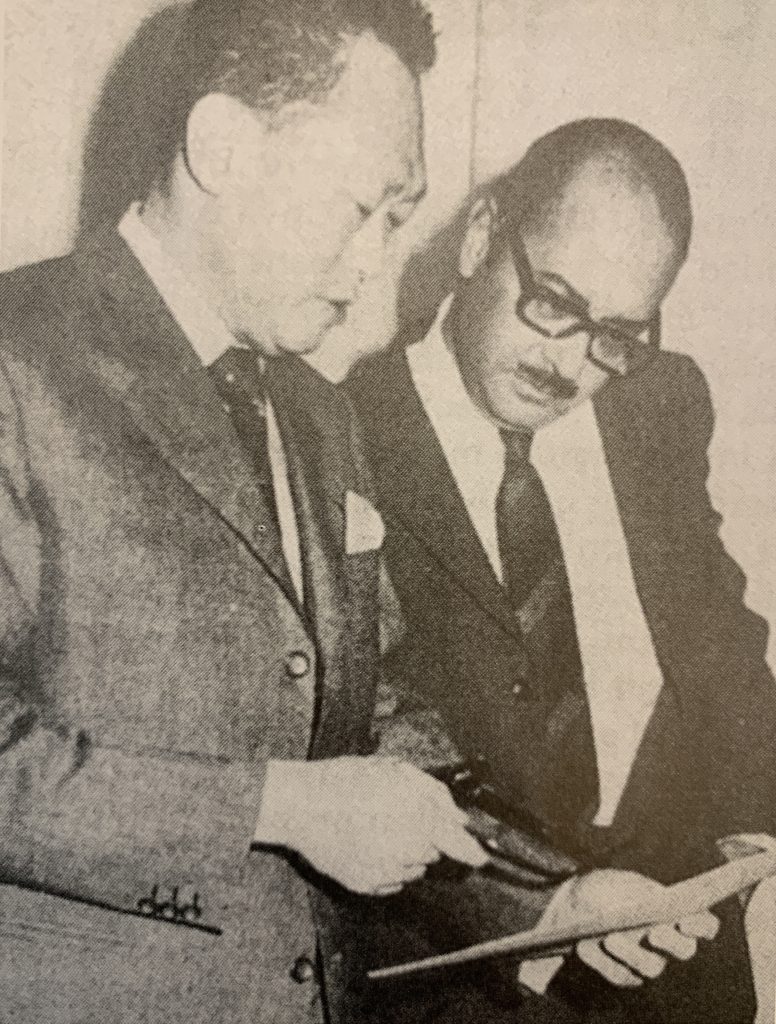

But few recall Bogaars as a prominent figure responsible for the covert security operation. He was head of the Special Branch from 1961 to 1965.

Trawling through pages of declassified British documents, I found out Bogaars was part of those secret Internal Security Council meetings with British and Malaysian officers, in which PM Lee and the Tunku were also present. It was in these meetings where Operation Coldstore was planned.

Bogaars was there for those meetings, according to the minutes, but seldom spoke, which makes me gather that he works behind the scenes while the politicians were on the frontline.

More than half a century has passed and sentiments are still split on whether Operation Coldstore was justified. While the official narrative maintains that communists had to be purged as they planned to subvert the state, some such as historian Thum Ping Tjin have argued that the operation was politically-motivated.

But on the rare occasions when Bogaars spoke, his analysis was sharp and his insights analytical. The book mentioned a meeting where he was asked by Toh Chin Chye, then Acting PM, on how Chinese voters would react if Barisan Sosialis members were nabbed. Barisan Sosialis was a splinter party formed by defectors from the People’s Action Party.

“His assessment of the feeling among the Chinese-speaking people in Singapore was that by and large they did not think of the Barisan Sosialis as directed by the Malayan Communist Party, and did not associate them with a communist conspiracy,” the minutes recorded him as saying.

In the 1980s when Bogaars was interviewed by Dennis Bloodworth for the book The Tiger and the Trojan Horse, he seems to have also questioned the move, specifically on some names proposed by PM Lee himself.

Bloodworth wrote: “Singapore had to ‘twist it a bit’ when submitting the crime sheets to the ISC in order to ‘get a kind of security justification’ for detaining James Puthucheary in particular, said Bogaars euphemistically.”

While even cabinet ministers like Toh and S Rajaratnam were kept in the dark during the lead up to Aug 9, 1965, Bogaars was one of three civil servants privy to the negotiations for Singapore to split from Malaysia. The other two were cabinet secretary Wong Chooi Sen and head of the civil service Stanley Steward.

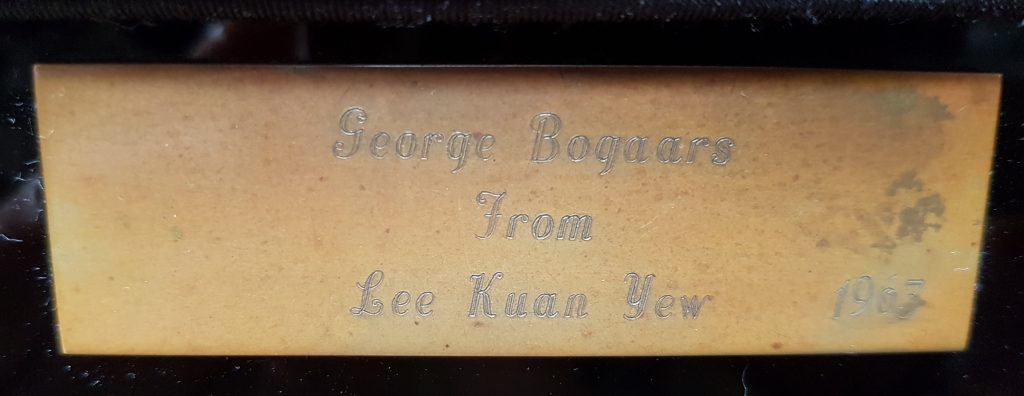

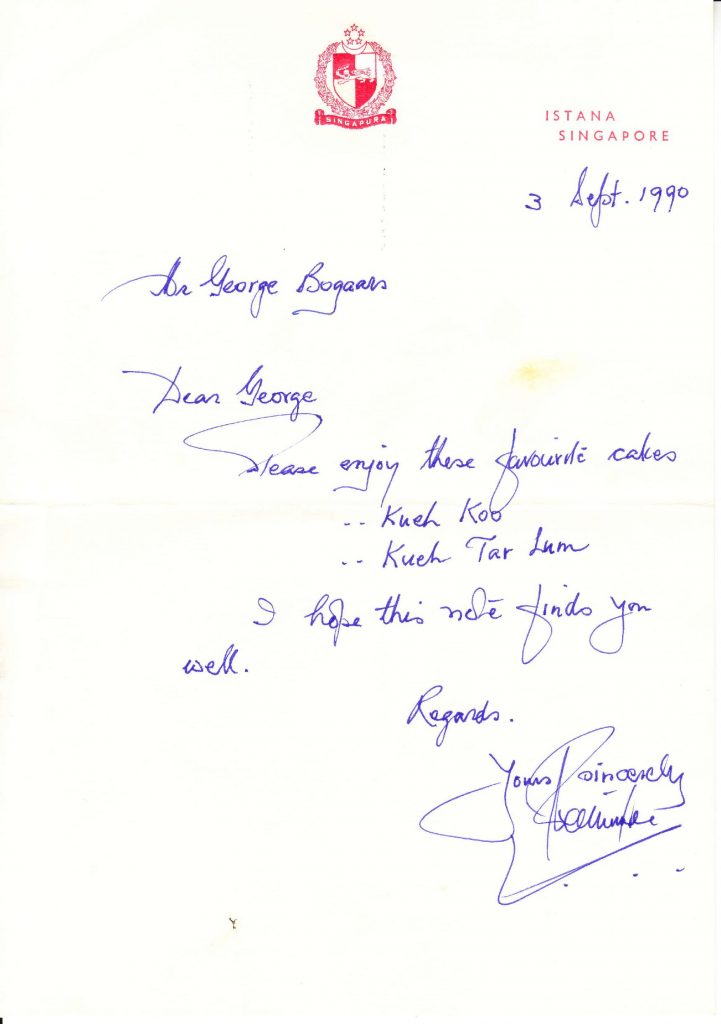

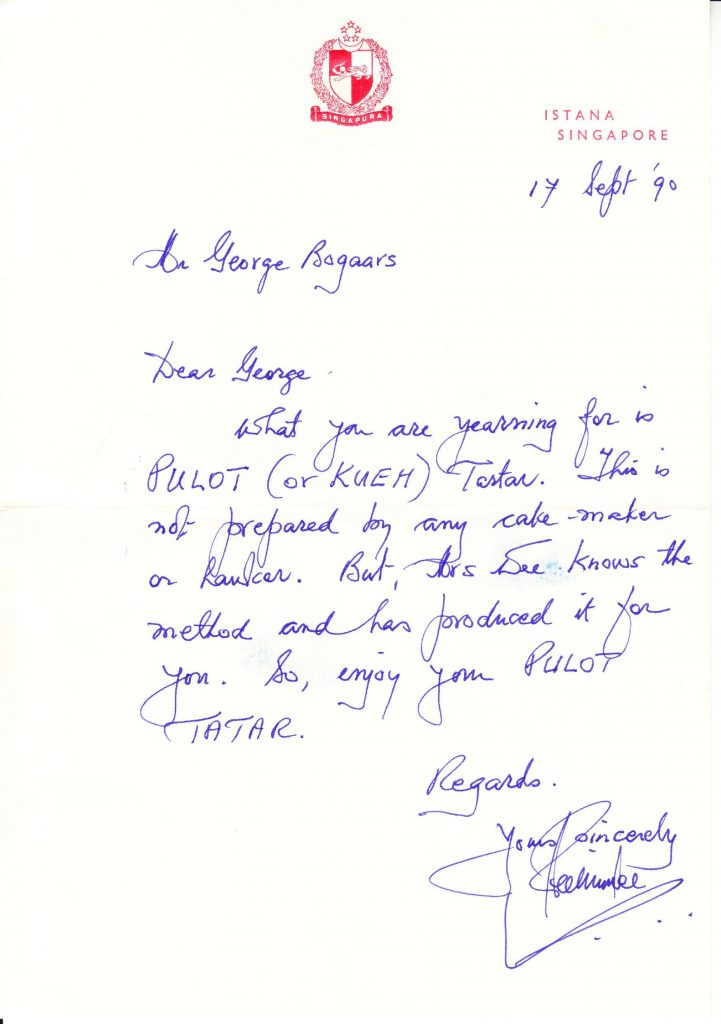

During these tumultuous times, it’s clear Bogaars was one of LKY’s trusted men whom he relied on for candid advice, and was an invisible hand behind these pivotal moments of our history. A pen-holder he got as a personal gift from Lee shows this highly-trusting relationship between both men.

History books give plenty of credit to founding PM Lee and his colleagues who fought for decolonisation. But we should remember others like Bogaars who had their backs and whom they sought advice from.

Singapore’s history wouldn’t be the same if the leaders were told something of the contrary and made a different decision. Unfortunately, the official narrative gave little play to those behind the scenes.

A vocal and forthright civil servant

Bogaars helmed the civil service from 1968 to 1975, at a time when Lee Kuan Yew was in his prime. We need little introduction to the founding PM: iron-fisted, fierce, and feared. It was a time when Singaporeans tended to be more deferential.

Yet, under such a climate, Bogaars had no qualms about speaking up even if what he said made the administration uneasy.

Once, Bogaars criticised the civil service for being “terribly overstaffed”—and this was in 1974 when he was its top leadership. Another time was when he lamented that civil servants were paid too little, and called for the salary structure and promotion criteria to be reviewed.

“There were too many middle management people doing executive work which could be done by junior clerks. He added that some posts were created to fill promotional needs rather than because of job demands,” Assoc Prof Henson wrote in the book.

In an interview for the book, former civil servant Dileep Nair recalled how PM Lee was scolding civil servants, including permanent secretaries, about the low proficiency of the English language in the bureaucracy.

As expected, nobody in the room dared to say anything. Except Bogaars, who suggested that teachers be recruited from Britain.

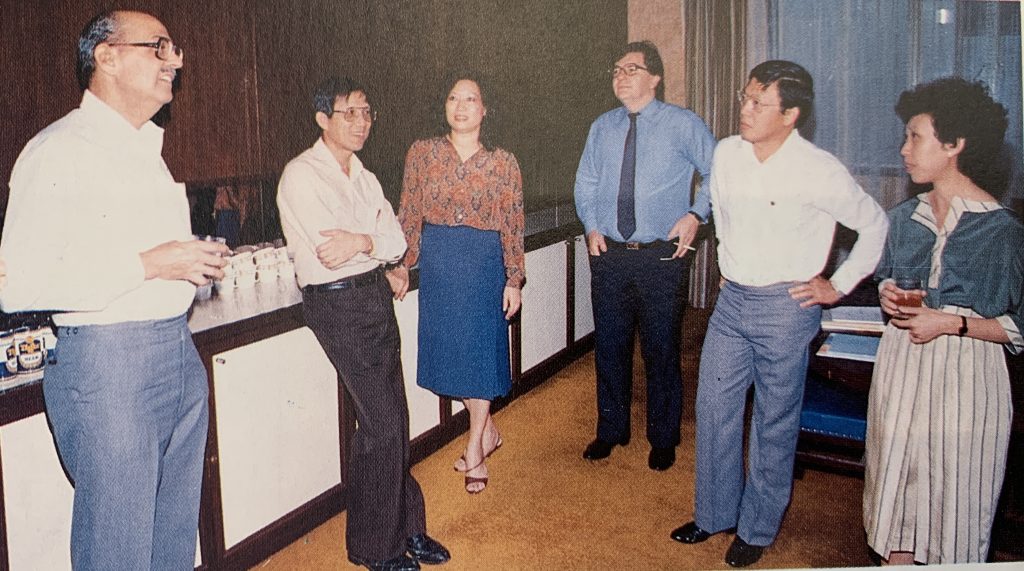

This was a generation of top civil servants—Bogaars, Ngiam Tong Dow, and Howe Yoon Chong—who dared to speak their minds and were more concerned with getting the job done right than to be politically correct.

Perhaps back then, they inherited the British political culture where civil servants see themselves on par with politicians, rather than as subordinates—similar to the relationship between the fictional Minister Jim Hacker and Sir Humphrey Appleby from the British comedy Yes, Minister.

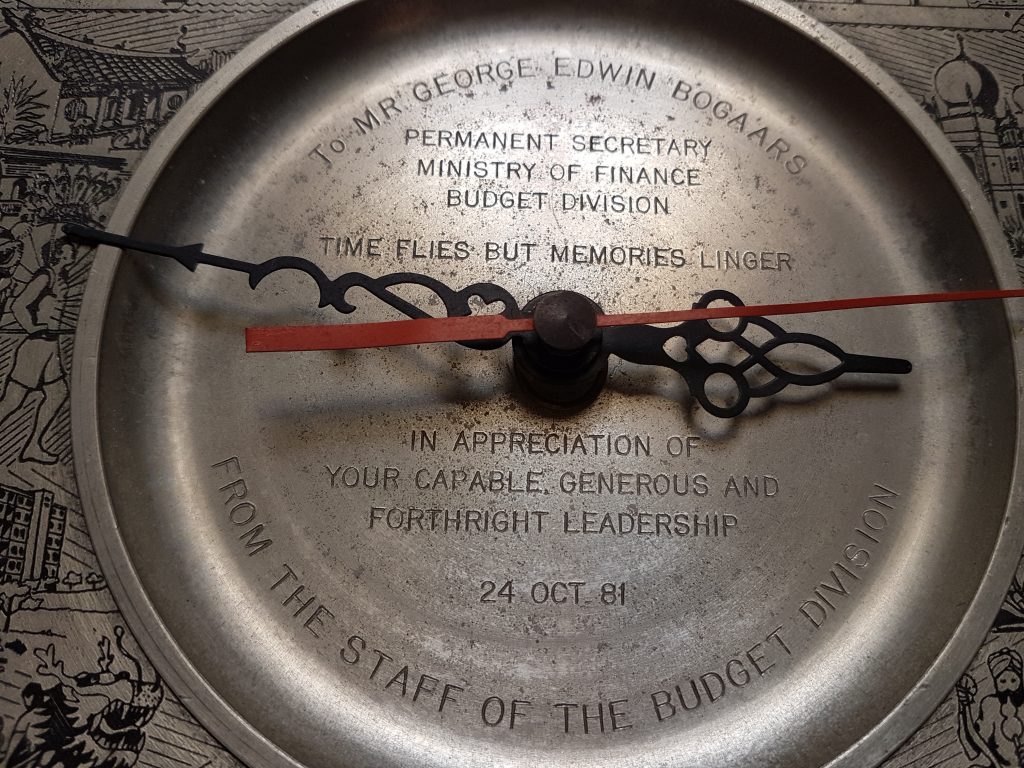

The relatively lower pay of civil servants then might also be why the likes of Bogaars were more outspoken. Assoc Prof Henson wrote that when Bogaars retired in 1981, he was earning about $6,000 monthly, which is equivalent to about $11,000 today. Less was at stake for them.

Salary data of top civil servants is not publicly available, but since their pay grade matches that of an entry-level minister, a permanent secretary may well earn at least $46,750 a month today.

With higher salaries these days, civil servants might be more cautious about speaking up and putting their well-paying careers on the line—a similar point made by the late Ngiam Tong Dow on ministerial salaries.

Philip Yeo, who used to be a permanent secretary in the defence ministry, was cited in the book saying: “Do you think that generation talked to ministers the way civil servants do now? In those days, they were equals.”

“When a minister or someone in authority or even a permanent secretary gets a junior civil servant to do something, he is not inclined to sit down and think whether there will be any repercussions and tell him when there are problems,” Bogaars was quoted as saying in the book.

He said it shouldn’t be a case of “mindless efficiency”.

Keeping the public purse in check

In his 29 years in the civil service, Bogaars spent most of them—14 years—in the Finance Ministry, in three different stints (1955-1961, 1970-1972, and 1975-1981). He had a reputation for being tight-fisted with the kitty, rejecting civil servants’ requests when they couldn’t properly justify the need to tap on public funds.

In fact, Bogaars was known among his subordinates to make amusing and witty comments when rejecting those requests.

A hilarious incident recounted in the book was when an officer overseeing the parks wanted a budget for grass-cutting. Bogaars rejected it and quipped that officers should instead breed goats which would eat the grass and produce milk.

This prudence with public monies extended to a revamp he mooted in the 1970s, where civil servants making budget requests would have to explain how objectives were to be met, instead of just listing items they needed to buy.

Such a system remains in place and helps ministries to always be on their toes, ensuring that money spent is linked to their overall targets.

To its credit, this attitude of frugality held by pioneers like Bogaars in the civil service is still upheld today.

Technically, notwithstanding presidential assent, the PAP government has parliamentary dominance and thus the carte blanche to give the nod for any expenditure, frivolous or otherwise.

Even during exceptions when it dipped into the reserves, the government repaid the amount afterwards, which they did after the first drawdown in 2009, even though there isn’t a legal obligation to do so.

“A government should only draw on past reserves in very exceptional situations, for example, when external events or crises pose a threat to Singapore’s economy or society,” said then Finance Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam during the Budget that year.

Bogaars knew that as a custodian of public funds, Singaporeans had trusted them to spend their money wisely and be fiscally responsible. It behoves the public service to stick with this strong sense of ethics because Singapore is a vulnerable country without natural resources. There is little to fall back on if a rogue government decides to empty the coffers and ruin the nation.

Unlike today’s civil servants, pioneers like Bogaars served under numerous administrations: The British, the Labour Front government, the Malaysian days from 1963 to 1965, and the PAP government.

They had greater awareness of power transitions. Governments came and went but the bureaucracy remained. This might be why they had a strong moral obligation to ensure the public purse was not abused by politicians with populist and self-serving interests. They knew that ultimately, civil servants should serve the country and not a political party.

It’s time for more recognition

After retiring from the civil service, Bogaars continued to chair Keppel Corporation and other companies such as National Iron and Steel Mills.

He faded from the public eye amidst financial troubles at Keppel. In 1983, he acquired 82 per cent of the Straits Steamship Company at $408 million, which was then the biggest corporate takeover in Singapore’s history.

But a shipping downturn at the point of acquisition put Keppel in a huge debt of nearly $845 million. Bogaars, blamed for the “bad buy”, was replaced as chairman by Sim Kee Boon in 1984. Many saw this as a fall from grace.

Eight years later, Bogaars died at 65 years of age.

But it wouldn’t do justice to his illustrious career and contributions if we were to judge Bogaars solely on this blotch. He played a historical role as a civil servant in nation-building at various milestones. The country we have today isn’t purely the effort of founding fathers like Lee Kuan Yew, but also those who loomed in their shadows and supported behind the scenes.

Our late former president S.R. Nathan, who had worked with Bogaars, said that he’s a forgotten hero. This is regrettable. It’s time we give more credit to pioneers like Bogaars—not just because they deserve it, but also for their stories to be shared and valuable lessons for future Singaporeans to learn from.

May this book start a national conversation for us to better acknowledge our unsung nation-building pioneers.

Not For Circulation: The George E. Bogaars Story by Bertha Henson can be bought at leading bookstores such as Kinokuniya and via NUS Press.