Top image: Stephanie Lee / RICE Media

“I’m HIV positive. I don’t know when and where I got it, so I would suggest you get tested, just so we can clear the air and put your mind at ease.”

It had been six months since I broke up with my first boyfriend, Alex*. Life had been going swimmingly until he sent me that text on a Saturday afternoon.

His diagnosis didn’t seem like something I should be concerned about. I was hypervigilant—even making sure he had recent negative STI test results before we became exclusive. So for all I know, he must have contracted the virus after we split.

We had an amicable breakup. I called off our relationship in January 2024 after spending most of Christmas realising I didn’t want to stay in what felt like a monotonous relationship in my 20s. We had a good run.

But deep down, I already knew his text was implying something crucial I didn’t know. Why was he telling me to get tested when we broke up half a year ago?

“Does this mean you cheated on me while we were together?” I replied.

“Yes. I’m sorry.”

Frighted With False Fire

Nothing prepares you for the gut-punch of thinking you might have HIV, let alone facing it at 20. Sure, it’s no longer the death sentence it once was, but let’s not pretend the stigma’s vanished.

Suddenly, all those school warnings came rushing back—teachers flashing grotesque slides of STIs, warning us not to sleep around. I did everything right (well, except the puritanical abstinence bit). How the hell did I end up here?

The day Alex contacted me, I was about to watch a theatre recital with my family—my sister’s big performance—and I had no means of getting tested immediately. So I disassociated.

To this day, I couldn’t tell you which Shakespeare character my sister played. I remember everything else in microscopic detail. How cold the theatre felt. How bright the stage lights were. How I sank into the upholstery, wishing to be swallowed into it forever.

The thing that kills you is the anxiety and uncertainty. Did I do anything to put myself at risk of contracting the virus? What will the rest of my life look like if I’m HIV positive? Do I deserve this? Will my family still accept me?

Down the WebMD rabbit hole I went, desperate to find some symptoms that would eliminate me as an at-risk individual. I felt my body for swollen lymph nodes, and tried to remember if I had lost any weight recently or had bouts of influenza-like illness.

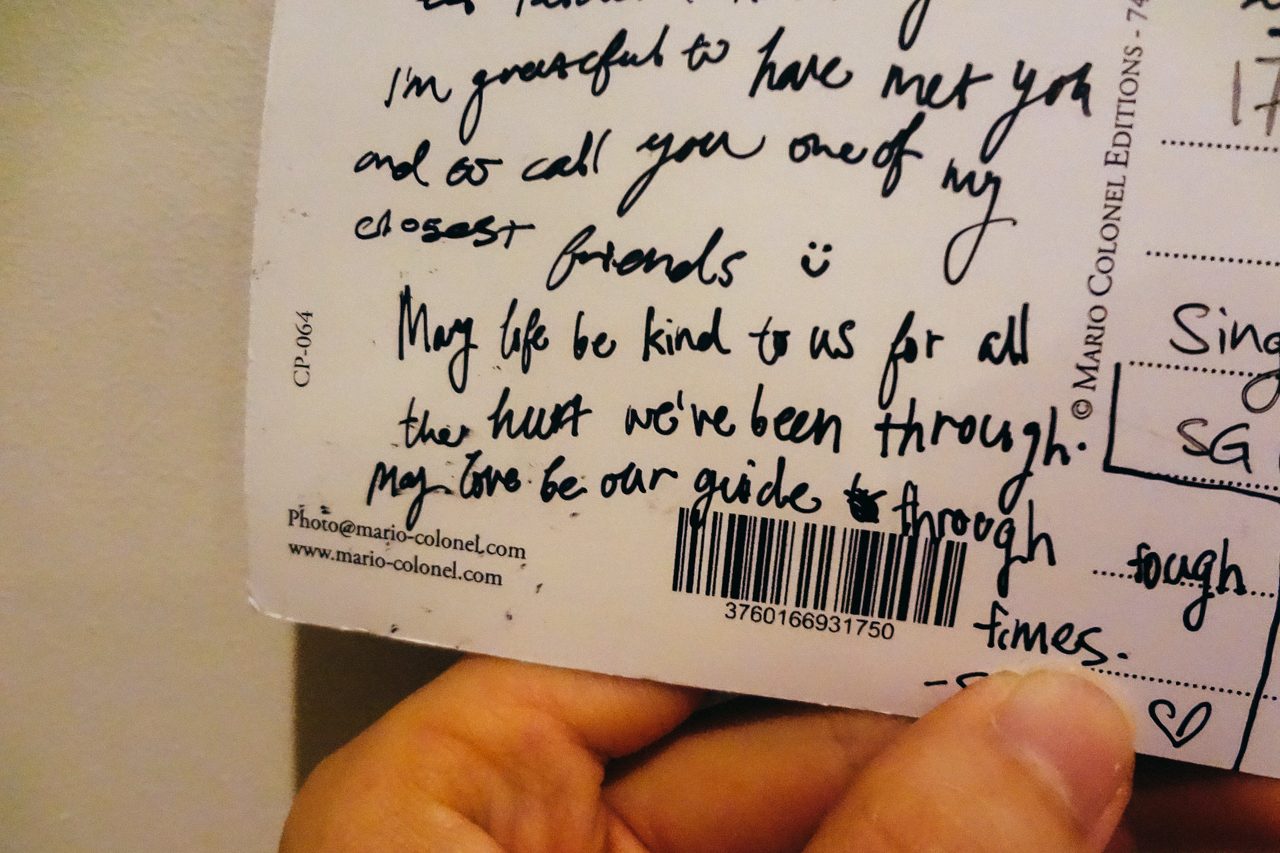

It was irrational, and I knew I had to take real action. I texted a friend, Poppy*, whom I knew I could rely on, and made a plan. The next day, I was scheduled to have a half-day work shift at a pop-up art booth in Kampong Glam. Poppy would help me man the booth, and I’d go get tested.

But where, though? That morning, I asked her if she knew where to get tested and what I’d need to prepare for. I saw the helplessness in her eyes as she admitted she didn’t know what to do, either. I had very few options because it was a Sunday, and most clinics close on Sundays.

Eventually, I found a clinic at Clarke Quay that looked decent enough, and most importantly, open. To my relief, the waiting room was empty. But even the absence of anyone around wasn’t enough to quell the nerves to say it out loud.

I could only muster up a whisper to the receptionist: “I need an emergency HIV test”.

“Oh. Can, dear,” she said with a weak smile, taking my pink IC from my hand. It was trembling.

Five minutes later and I was sitting in front of a doctor. I told him what happened.

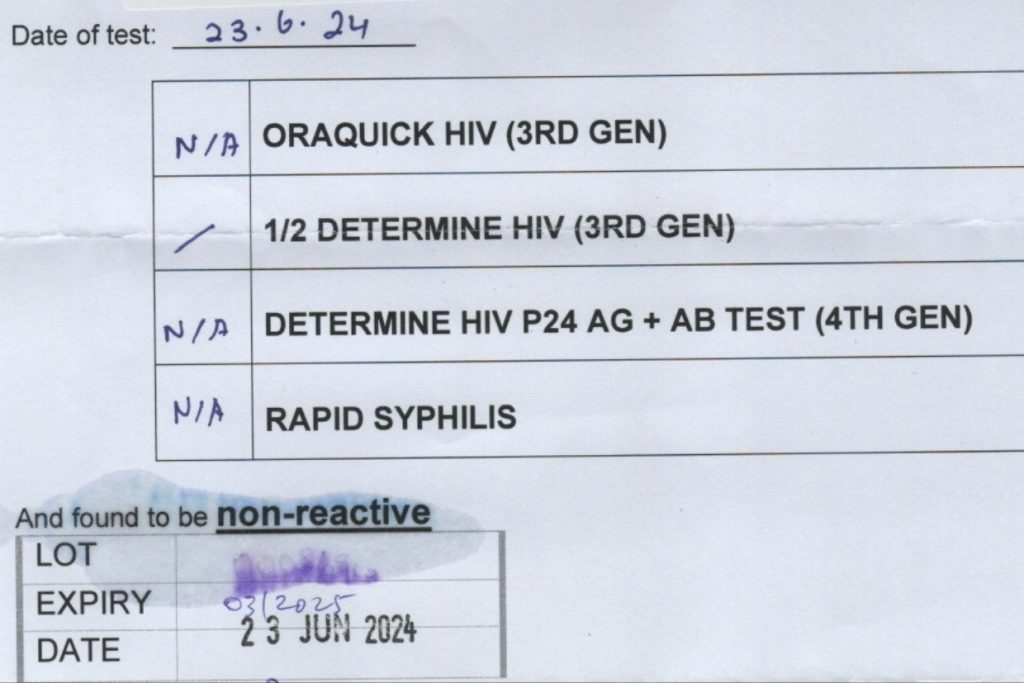

He responded calmly, though I could see pity in his eyes. The test—a HIV rapid test—involves a finger prick onto a litmus paper.

“It’s just like an ant bite on your finger, nothing severe,” he assured. As the solution with my blood rushed down to the indicator, I turned away and waited.

“It looks like… you’re okay,” he says after the longest 30 seconds of my life.

Those words opened a floodgate of hot tears. It was the first time I cried since receiving the text.

When the Worst is Over

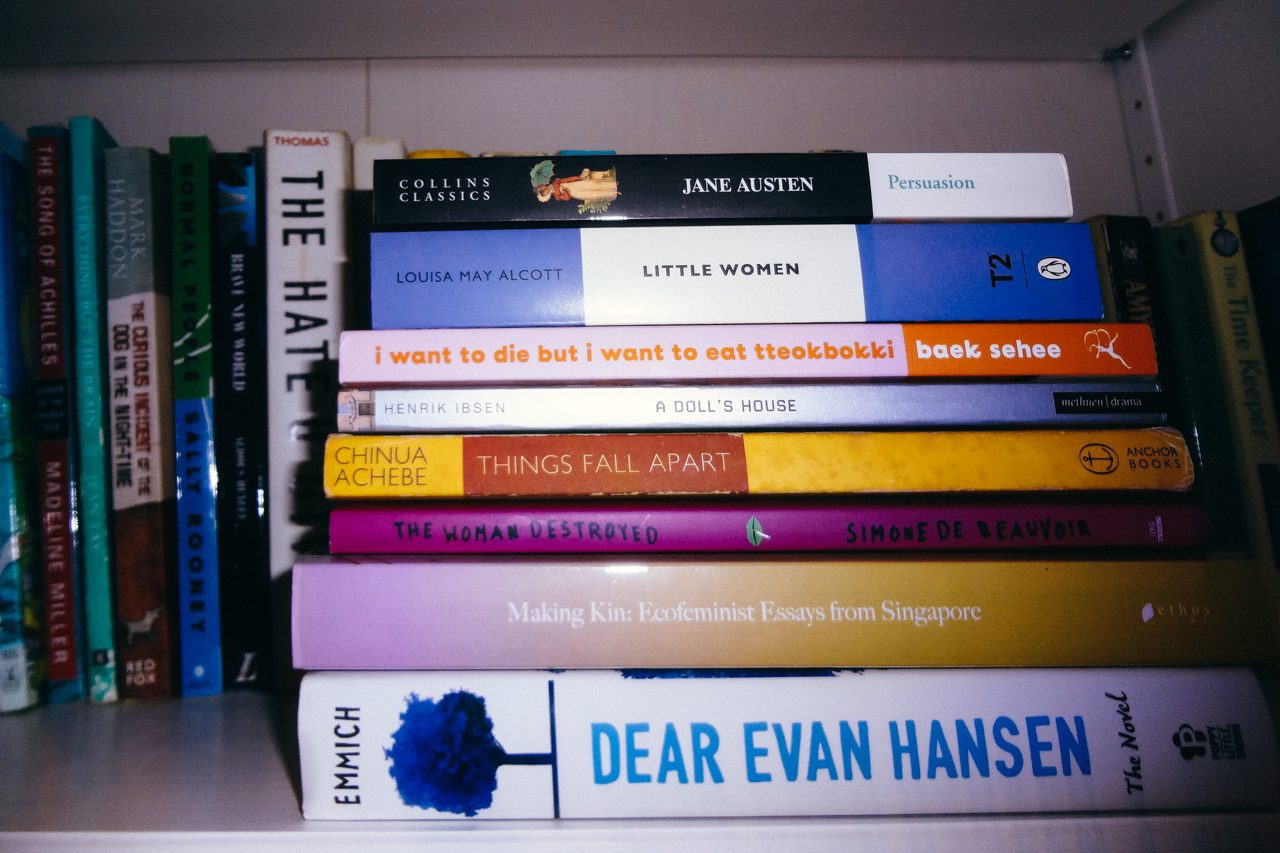

But this isn’t a mere anecdote about a HIV scare. It’s about the messy, often isolating path to healing in a society that still flinches at conversations about sex, illness, and shame. When silence becomes the norm, we don’t just avoid discomfort—we let it eat away at people when they need compassion most.

Even so, having that conversation felt impossibly hard. And that’s saying something because I’ve always had a good relationship with my parents, perhaps better than most. My father, dutiful and protective. My mother, observant and intelligent beyond comprehension.

So it was no surprise that the second I stepped through the front door, my mother asked me if something was wrong. Maybe she saw it on my face, worn down by the past 36 hours.

“Before I say anything, I need you guys to know that I am healthy and safe.”

And then I came clean.

It was the first time in a long while that I saw my mother cry, wishing I had asked her along to the clinic. She also made me seek a therapist.

My dad’s face and neck flushed red. It later became clear that he wasn’t angry at me, but with Alex. But I took the punishment all the same when he didn’t speak to me for two weeks.

My mum immediately scheduled an emergency gynaecologist appointment. Upon telling my gynaecologist what had happened, the doctor offered some disapproving quips and tsked in judgment.

“Kids nowadays, all like that…” she trailed off.

Like what? I was cautious; I was faithful. I’d argue that my biggest fault was being in love. Was humiliating me going to change what happened?

A plethora of tests awaited me, including my first premature pap smear, something sexually active women should be getting every few years once they turn 25 in Singapore. They also took samples of my blood and urine.

Judgmental as the gynaecologist was, she was admittedly good at her job. She previously helped me through major ovarian cyst surgery. She fulfilled the Hippocratic Oath, but never failed to pepper critical comments here and there—all dutifully endured quietly.

It was voices like these that implied that I was at fault, fuelling my shame. The trauma of the first 24 hours of the message was light work compared to this.

As the guilt and hurt grew, I knew I was headed toward permanent damage if I didn’t seek professional help soon. Finding a suitable therapist proved to be another challenge. Desperate, I penned a message to a counselling service that was a five-minute walk from my house:

“I need a therapy session to process a trauma-inducing event that happened recently. It impacted me and my family, which makes it difficult for me to turn to them for support, as they are also in need of guidance.“

After a brief assessment, I was referred to a therapist who specialised in emotional and compassion-focused therapy for individuals battling shame, self-criticism and emotional trauma.

It does feel like a Sisyphean task—each time I thought I was making progress during a session, my therapist would knowingly ask me during the next session if I engaged in negative self-talk since we last met. And indeed I had, even though I did nothing wrong.

Once in a while, I’d be caught off guard when my parents would ask, “Is your therapy working?”

And then I wouldn’t know how to answer honestly. Even though I learned from therapy to be gentle and kind to myself, a part of me was still convinced that I deserved to be punished.

That’s what happens when shame, fear, and moral policing become the foundation of how we’re taught to think about sex.

One Year On

Recalling this tumultuous period each time feels nerve-wracking. I’m still unsure if people will see me differently.

That pang of guilt hits every now and then. When my family takes jabs at my bad taste in men, when I fear being judged for my past, and even when I had to take another doctor-recommended lab-based HIV test earlier this year (to be extra sure I was risk-free).

Recently, I was having a meal at a food court with my family, and the topic of health check-ups came up. When I chimed in on the conversation with my own experience testing for HIV, my dad, without missing a beat, cut in:

“Shh, don’t let people hear you. Don’t talk about that anymore.”

In a way, I understand why stigma over such things still exists here. My dad was raised on old-school values. He refuses to discuss sexual health openly. He worries people will think I’m promiscuous.

But older generations show solidarity in other ways. When I started seeing that they, too, were trying their best, it became easier to accept whatever form of love they offered—from showing enthusiasm over my dating life to celebrating my last therapy session with a nice dinner.

And if there was a silver lining to all this, I’ve become passionate about educating others, thanks to unintentionally acquiring a cache of health knowledge along the way. Yes, I’ve become that woman who nags her friends to get tested and go for regular health checkups.

My teenage sister was unaware of the perils of HIV—to her, my health scare sounded like a close shave with COVID. It was only when I explained the lifelong implications of sexually transmitted infections and diseases that she understood why I was so serious.

Recently, Poppy called me, panicking about her first pap smear appointment. She wanted to cancel it, under the impression that it would be like a biopsy. I debunked it.

Wouldn’t you rather know what you actually have than live with risk? Skipping screenings and tests is blatant avoidance, but I know women who have overdue pap smears because they’re scared of the pain (of which there was none for me).

Not addressing sex and sexual health directly and openly has led to a nation of embarrassingly uninformed young people. I consider myself resourceful, but even then, it was such a struggle to find trustworthy professionals to guide me through my ordeal.

Living in a shame-based society leaves little room for people—especially confused and scared youths—to ask for help when they need it. When schools vilify sex and parents sidestep ‘the talk’ altogether, not being honest about sexual health and how young people are actually navigating sex today feels like a collective moral failure.

‘Good To Be Safe, Hor’

One year on, I’ve finally regained my confidence. It’s easy to be influenced by other people who make you feel ashamed—but it’s just lingering, baseless stigma that influences their perceptions.

If I continued feeling resentment or listened to outsiders, I’d be punishing myself more.

Only I know what I need to heal. People may try to help or hinder, but the responsibility lies with me to make the discernment.

Just last week, I attended a routine gynaecologist appointment. She asked me if I wanted any tests, with one eyebrow raised.

“Yes, I want an STI panel,” I said confidently.

For the first time since meeting her, she hesitantly offers: “Good to be safe, hor.”

For now, only by feeling and remembering every ounce of shame, pain and fear—and still choosing to see the good in everything—can I live with full intention.

It’s a daily effort that I’m still navigating, reassuring myself that people are still good. And there is nothing for me to be ashamed of.