All images by Xue Qi Ow Yeong for RICE Media unless stated otherwise.

“The first stroke of good luck in my life was to be born in Singapore.”

Veteran diplomat Kishore Mahbubani—a man who served as Singapore’s United Nations representative and once chaired the United Nations Security Council—says this in the first chapter of his new memoir, Living the Asian Century.

It’s the sort of sentiment that young Singaporeans plagued by ennui and nihilism might find hard to relate to. It’s also the sort of thing you can truly believe in if you’ve lived through adversity and come out swinging on the other side.

The year was 1948 when Kishore was born to migrants from India who’d settled in Singapore by chance. Growing up in a poor family in pre-Independence Singapore, he was so underweight he was forced to drink a ladle of milk in school every day. The small house on Onan Road he lived in had a bucket for a toilet that was replaced daily by nightsoil men.

For Kishore, luck didn’t mean a life free of struggle. Rather, the good luck he’s talking about refers to the opportunities Singapore gave him: a prestigious education, a President’s Scholarship, a career in the foreign service, and the opportunity to advance Singapore’s interests in the United Nations.

Still, the definition of luck differs across generations. Even though none of us have to poop in a bucket anymore (thank god), we’re plagued by modern monsters like cutthroat competition, a breakneck pace of life, and cyclical burnout.

Is being born in Singapore still a cause for celebration today?

Southeast Asia Is Your Oyster

Back then, life was simpler, but still tough. About 940,000 called our island home in 1948. Living conditions were abysmal in those post-World War II years. Much of the population lived in overcrowded slums with poor sanitation. Drop-out rates were high.

These days, being born in Singapore means you’re joining 5.637 million others on this tiny island. Public housing is now coveted. About 33 percent of the adult population have a university degree so it’s no longer a golden ticket to success.

Living conditions are markedly better now, but we’ve got first-world problems. Million-dollar HDB flats are now a thing. Economic optimism is at an all time low. Workers are mentally and physically exhausted.

I’m genuinely curious what Kishore has to say about the young Singaporean’s prospects today, especially since he’s lived through the nation’s dramatic transformation. As it turns out, he’s equal parts empathetic and optimistic.

“To some extent, I understand the frustrations of young Singaporeans because Singapore is a small place. And opportunities in that sense may be limited,” he offers.

“But at the same time, it is a fact that Singapore now lives in one of the most optimistic regions in the world, Southeast Asia, because of the success of ASEAN.”

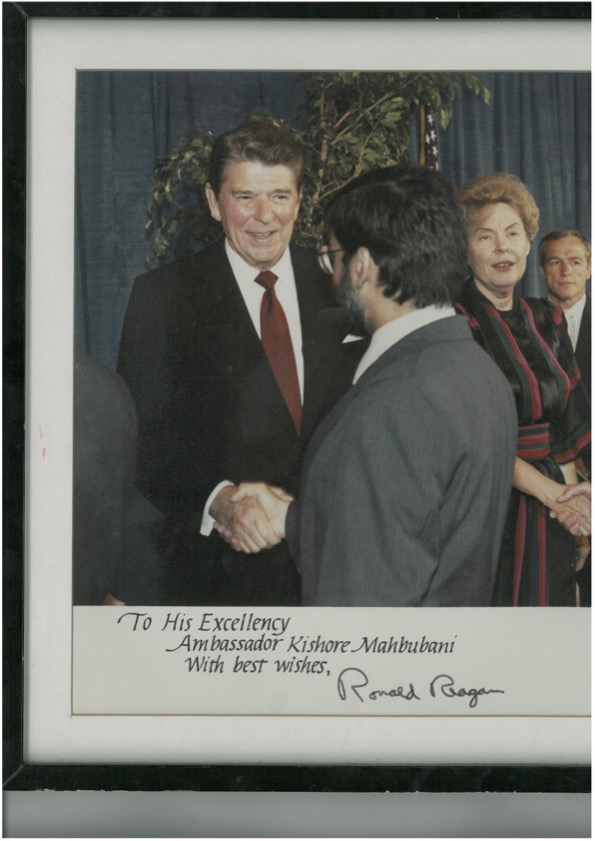

Indeed, as Kishore regales his life’s exploits in his memoir—from the time S.R. Nathan threw a file at him to the time he met Ronald Reagan—the reader is constantly reminded that none of this would have happened if he hadn’t been born in the right place, at the right time.

This ‘right place, right time’ sentiment still applies to young Singaporeans today, he says. Only instead of just Singapore, Southeast Asia is our oyster.

Some young Singaporeans are reluctant to take postings in other Southeast Asian countries because they’re comfortable here, says Kishore, citing conversations with employers. But success only comes when you take risks. He recalls being posted to Cambodia on a diplomatic assignment when he was 25. Then, the country was at war and shellings were a daily occurrence.

Back then, people aspired to move to the West and work in places like London. As a President’s Scholar, he probably could have found his way there if he really wanted. But Kishore accepted the Phnom Penh posting, believing that taking the risk was worth it.

“I must confess, the adversity [in my life] was terrible. But the suffering made me much stronger as a result. So a little bit of adversity and challenges for the young Singaporean can be a very useful growth experience.”

It’s tough to reconcile that Southeast Asia holds viable opportunities. When most people my age think of working overseas, they probably think of chasing their dreams in the Big Apple, or being in the thick of technology in Silicon Valley, or finding the meaning of life on a farm in New Zealand.

Rarely do our overseas fantasies involve our Southeast Asian neighbours. But with the rise of Asia—economically and culturally—we’d be remiss not to broaden our horizons beyond the typical and look to our swiftly developing neighbours.

Work’s Supposed To Be Hard

Another hard truth that we’re going to have to accept is that we might not be as successful as our parents, and that’s okay. In Kishore’s era, outperforming your parents was as easy as graduating from secondary school. These days, the “escalator” of social mobility seems to be slowing down.

To that, Kishore offers: “Life cannot be just a pursuit of material goods. You’ve got to carry out work that you find rich and fulfilling”.

“The advantage of living in Singapore is that a lot of the new jobs that are coming are very high value-added jobs. And so they’re very challenging. You don’t get the same kind of routine jobs as in the past.”

Throughout our conversation, it’s clear that the fire that fueled his climb out of poverty hasn’t gone out.

I think back to one of the first few chapters of his book, where he talks about how most Sindhi boys go on to work in textile shops after finishing their education. As a Sindhi himself, he had nearly gone down that path after junior college.

If all he aimed to do was to do better than his parents materially, that would have been a perfectly respectable path to take. As he candidly recounts in his memoir, his father couldn’t hold down a long-term job due to drinking and gambling, and his mother was unemployed. His family really could have used that textile shop money.

Instead, the man took a chance on the University of Singapore (now NUS), and ended up dedicating the last 50 years of his life to geopolitics.

We’ve all got this innate desire to prove ourselves to our parents and to chase after material success. But we can’t let that be the only thing guiding our career choices. If Kishore had done that, he might very well be tending a textile business now instead of launching a memoir.

I get it. It’s overwhelming. We’ve got to make ends meet. And find fulfillment at work. And take risks. All at the same time.

But looking at the enthusiasm with which Kishore describes his work at the Asia Research Institute (ARI) in National University of Singapore—as well as the numerous speaking engagements he’s got coming up—I can’t help but wonder: How many of us would be this happy to be doing what we’re doing at 75?

Dissecting The Roiling Discontent

Make no mistake about it—life in Kishore’s era was harder. But why, then, are the young Singaporeans of today more unhappy?

These days, the growing middle class and growing number of educated people are naturally more critical, Kishore muses.

“When you develop a middle-class society, when you have a highly-educated society, they’re not going to behave like docile lambs. They are going to speak out and be more critical. It’s logical. But I do think that the government is aware of this, and they realise that they have to engage them.”

We see this play out in everything from our political environment to the way citizens speak up for causes they care about.

In particular, measures to tackle the rising cost of living and the ageing population are what SIngaporeans want to see from our government, according to a Milieu poll published on July 31st. We also want our leaders to show accountability and integrity, the poll revealed.

Even as 83 percent of Singaporeans polled say they are confident in the next generation of leaders, the opposition’s vote share has been growing over the years.

Kishore admits that he grew up in simpler times. There was no leader of the opposition back then. The People’s Action Party (PAP) enjoyed such a strong standing with citizens that there was a popular saying: the PAP could put up a donkey in a PAP uniform for election and still beat an opposition candidate.

“The opposition today is giving a real fight to the government. And that shows how the political environment of Singapore has changed. And it’s a natural result of the fact that we now have a middle-class population and the middle-class population clearly wants to see a two-party or three-party system.”

Still, Kishore staunchly believes that we’ve got the right people leading us. He tells me he’s a fan of Prime Minister Lawrence Wong (“great communication skills”) and President Tharman Shanmugaratnam (“brilliant at every job he’s taken on so far”).

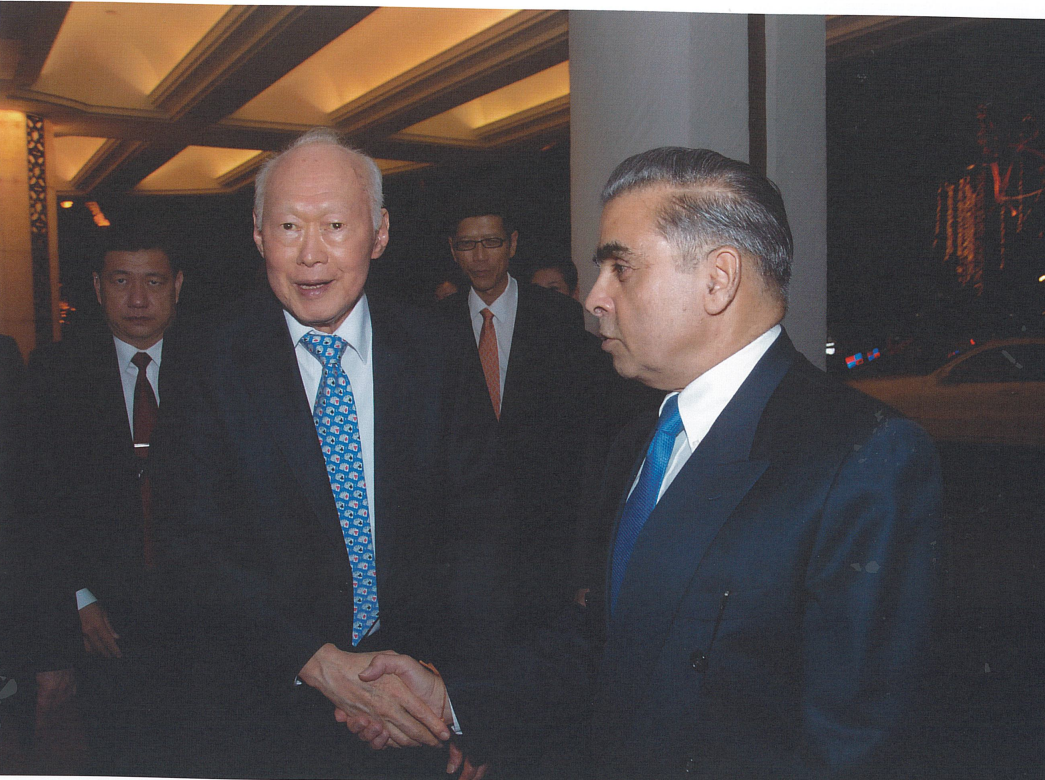

His optimism also stems from his confidence in the political culture established by founding fathers Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee, and S Rajaratnam.

To much of Singapore’s older population, these founding fathers are shining heroes and icons. To Kishore, they were people with whom he could break bread. These founding fathers would pick Kishore’s brain on worldly affairs.

He knows they weren’t perfect. In his memoirs, he tells of times when Lee and Goh were in conflict. And Lee was often a harsh boss. Once, during a particularly hard dressing down, Lee even asked grilled Kishore on why he didn’t have friends.

Kishore is empathic when he tells me that the one thing he wants young Singaporeans to know is that our founding fathers were undeniably human. But they were also brilliant.

He writes in his book: “The differences between Lee and Goh have never been fully revealed or discussed in public, and some Singaporeans may be troubled by such revelations. But Singapore should be brave and self-confident enough in its history and accomplishments to be able to admit that not everyone agreed all the time.”

He explains that putting our leaders on a pedestal does nothing to inspire the future generation. It’s the unvarnished accounts of their humanness and their struggles that will make them relatable and galvanise Singaporeans.

“Americans, for example, revere the founding fathers, and that common reverence of the founding fathers is a source of great unity in the US. And frankly, our founding fathers were as brilliant. And I sometimes say provocatively, probably more brilliant.”

The 21st Century Singaporean

As we celebrate 59 years as a nation, I wonder how many of us are genuinely excited for our country’s future and how many are more happy about the long weekend. Before speaking to Kishore, I might have put myself in that latter group.

But I don’t think Kishore’s optimism for our country—and Asia in general—is misplaced at all.

He’s very convincing as he breaks down his forecast for me.

“Now, the 19th century was the European century. And London was the natural capital. The 20th century was the American Century. New York was a natural capital. Now ask yourself, which city can be the natural capital of the Asian century?”

Even though being born in Singapore kinda feels like sliding headfirst into a Sisyphean cycle of work, work, and more work, there is much to be thankful for. For one, we’re well placed as the potential capital of the Asian century. For another, it’s a tremendous privilege to be grappling with first-world problems instead of the abject poverty previous generations suffered through.

Every country has its own problems—Kishore tells me that the pessimism in Europe and the UK is “enormous”—but it’s up to us to make the most of our lot.

“I think to have to struggle, is not a bad thing. It’s a good thing. And young people shouldn’t expect that life will be smooth sailing. It’s good to experience rough waters. That’s the moral of the story.”