This story is part of RICE Media’s Storytellers initiative, a mentorship programme for budding content creators to learn about the art of creative non-fiction. This piece is a product of a partnership between RICE Media and Singapore Management University (SMU) for its Professional Writing module.

Top image: Nicholas Chang / RICE file photo

With a population of around 6 million people, you might think that the crude death rate in Singapore—at approximately 69 deaths per day—is just a number.

But would your perception change if that meant that every 20 minutes—the same amount of time it takes for someone to eat lunch—someone in Singapore is grieving the loss of a loved one?

In our busy lives, mortality rarely surfaces in our minds, except for the times when we happen to come across news of someone passing on social media or the news.

Even then, we rarely pause to consider what it would feel like if our loved ones were to meet a similar predicament, often taking their presence for granted. But death comes knocking on every person’s door, eventually.

A new technology—labelled ‘grief tech‘—has been gaining traction amongst the bereaved as a new channel to manage their grief, utilising AI to create chatbots and virtual reality simulations that allow the bereaved to interact with and find the closure that they require.

Something less discussed, however, is how grief can be amplified by regret, which deepens the emotional weight of loss.

Take, for instance, the regrets of not spending enough time with loved ones, leaving words unspoken, or taking their presence for granted while they were still alive.

And yet, despite knowing that regret often stems from inaction, why are we as Singaporeans still so unwilling to openly express love and affection for those who matter to us most?

What We Leave Unsaid

“I can’t remember the last time my family and I have openly expressed affection for one another. But I think I can count the number of times we’ve said ‘I love you’ using only my fingers,” Alicia says.

The 23-year-old Singapore Management University (SMU) undergrad explains that her family never had the tendency to verbally express affection toward one another. Over time, this became the norm—an unspoken culture her siblings absorbed too, shaping her belief that saying “I love you” is strange, even unnatural.

“It feels really awkward hearing the words come out of my mouth. I’m just not used to it,” Alicia adds.

She is not alone in facing this phenomenon.

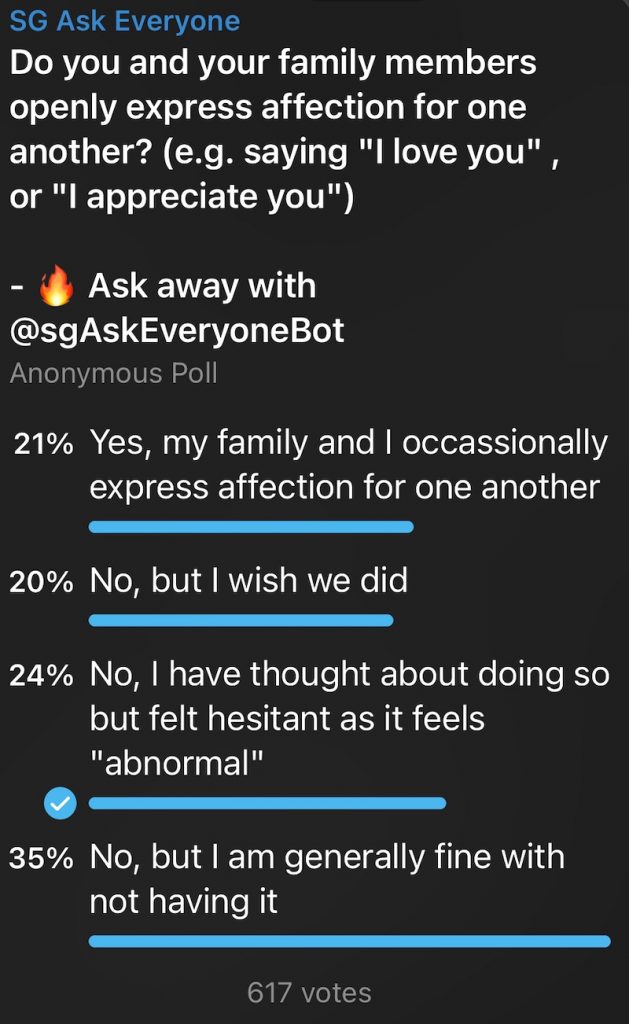

A poll initiated on a Singapore Telegram group shows that 79 percent of 617 respondents voted that they do not openly express affection towards their loved ones.

Many of us may resonate with growing up in households where affection is rarely expressed openly or verbally.

This begets the question: Is the reluctance to express affection for our loved ones hardwired into us as Singaporeans?

Research shows that children tend to develop emotional behaviours from how their parents express and teach emotions.

Then, we can reasonably expect the persisting lack of verbal and open expression of affection in Singaporean families to have been passed down from generation to generation, effectively perpetuating this phenomenon.

Perhaps most of us have eventually adopted and grown into this ‘culture’ through our adolescence and into adulthood. Gradually, we become uncomfortable with expressing affection.

Looking back at my own experience, I, too, realised that I am a victim of this phenomenon.

I recall the occasional “I love you” that I would say to my mom when I received birthday presents back in primary school. But it wasn’t until now that I realised her response (“Mummy loves you also lah!”) carried not just appreciation, but also a hint of awkwardness.

I’ve also come to realise that as I continue to age, the warmth of “I love you” that I used to say as a child has gradually changed to a dull “thank you”.

For some of us, we may have experienced occasions where we have expressed our affection for our loved ones through words, and it ends up worrying them instead—an indication that we subconsciously regard such acts as irregular or abnormal.

Alicia recalls a time in secondary school when her class was asked to call their mums on Mother’s Day, to tell them “I love you”.

“Instead of reciprocating with an ‘I love you,’ my mum was audibly worried. The first response she gave me was ‘what happened?’—as if something bad had happened to me,” Alicia adds.

While it might be part of our culture to avoid verbal expressions of affection, could there be something else that has contributed to this phenomenon?

A Straits Times article, which featured National University of Singapore (NUS) associate professor Feng Qiushi, who teaches sociology and anthropology, believes that Singaporeans are simply too occupied and stressed in their daily lives to express how they feel.

A Cigna Healthcare study also revealed that only 31 percent of Singaporeans are confident that they can manage their emotions. If we can’t manage our emotions, how do we even begin to express them?

Time and distance play a part. When asked whether work commitments have reduced family time, Alicia acknowledges that the busy schedules and work commitments for both her and her parents have limited the time they spend together.

“I’m not sure if this has impacted the emotional connection that I have with my family, but I definitely think having the opportunity to spend more time together will help strengthen my relationship with my parents,” Alicia reflects.

Perhaps the hectic lifestyles we lead in Singapore have inhibited our inclination to openly express affection for our families, exacerbated by the declining time spent with one another.

But if that is the case, how do we, as Singaporeans, display affection for our loved ones?

Tough Love, Singaporean Style

Indirect displays of affection are one channel that we, as Singaporeans, use to express our love.

Some of us may remember, in our teenage years, when we began to distance ourselves from our families, sharing less about the events happening in our lives, and even began to grow rebellious.

Jordan, a 24-year-old undergraduate, shares how he gradually spent less time at home when he was in polytechnic after forming new social circles and actively engaging in co-curricular activities.

“That period was when I became the most emotionally distant from my parents,” he remarks.

Jordan admits that he often felt annoyed from his parents’ constant nagging — telling him to stop staying out late too often and going to bed earlier.

“While I know that they were simply caring about me, I couldn’t help but feel annoyed, as I simply wanted to live my life back then,” Jordan explains.

“I think the fact that I spent less time at home and had fewer physical interactions with my parents could have driven that emotional wedge deeper for me. I just felt like they couldn’t relate to me.”

It wouldn’t be surprising if many Singaporeans have experienced something similar to Jordan, where our parents show their love and care for us in indirect ways.

Just very recently, my dad noticed that I was drinking several cups of black coffee a day. He chided me: “Cut down on the coffee, if not your heart might stop one day”. I knew he was just caring for me in his own way, but it probably wasn’t the best way to express it.

There is, in fact, a famous Chinese saying: “To hit is to dote, and to scold is to love”. After all, who would spend the time and effort to nag if they didn’t care?

Well-intentioned as they might be, these actions might end up doing more harm than good if the receiver misinterprets them.

Alicia recalls how her parents used to set a curfew for her till she was 19, chiding her for returning home late: “I knew they were just looking out for me. But during that period, all I thought about was how unfair it was for me not to have my freedom.”

“I don’t feel a particularly strong sense of love or care from the indirect ways my parents show it. Sometimes, I do wish they could be more open and generous with verbal affirmations instead — it would create a more loving and supportive environment, which I would really appreciate,” Alicia admits.

“Though talking about this now has made me realise that I should try to be more open with verbal affirmations as well.”

Love That Moves in Silence

Perhaps the most common way we express our affection for our loved ones is through acts of service.

When we are desperately trying to study for an exam the following day, or having to work overtime at home, our parents may quietly appear with a plate of cut fruits or a bottle of bird’s nest drink, insisting we finish it, telling us it’s good for our health.

“Every time I start to fall sick, my mom would notice and take the trouble to buy a bottle of herbal tea for me,” Alicia says. “Though I do appreciate it, I realised I haven’t explicitly expressed that to her.”

In Jordan’s case, he admitted that he didn’t realise how much he had underappreciated the little things that his parents would do for him, such as driving him to and from his army camp during his national service days.

“I think I might have taken these for granted, as if it’s something normal instead of realising that this is how my parents show their love for me.”

While many of us may subconsciously appreciate these silent acts of service by our loved ones, we often do not let them know how much it truly means to us or how much we appreciate them.

Instead, a simple ‘thank you’ is what we typically respond with—somewhat underwhelming and undermining our true feelings for our loved ones.

Dr Kenneth Tan, an assistant professor of psychology at SMU, shared in an interview with The Straits Times that he doesn’t feel that it is problematic that we express affection in different ways, such as through acts of service. NUS associate professor Feng Qiushi claims that doing so does not equate to our “emotional inner lives being any less rich than those of more outwardly expressive cultures”.

But things may become complicated when feelings of regret begin to haunt us—when we realise we haven’t expressed our love and appreciation in words towards our loved ones, and will never have the opportunity to do so again.

“After my grandfather passed on, I realised I had never really verbally expressed my affection for him or told him that I love him,” Alicia recalls, her regret evident. “I think about it sometimes and still regret not doing it, because I think at least for once, he would have loved to hear some words of affirmation from me.”

Alicia also mentioned that she remembers her grandfather’s favourite dessert—Rochor Original Beancurd—and would occasionally buy it for her grandfather.

“I didn’t really think much about it. I just knew my grandfather liked it a lot, so I would get the beancurd for him every time I happened to pass by the shop,” Alicia adds.

“Thinking about it now made me realise that I am also guilty of showing affection through acts of service instead.”

The Power of Words

While many debate over the pros and cons of expressing affection directly through the use of words, one thing that remains certain: Words are free.

Why not use them to let our loved ones know we love them and appreciate all that they have done for us?

“I love you” is uniquely powerful.

I’ve realised how much I haven’t said to my parents—my love and appreciation for all the things that they’ve done for me in the past 25 years of my life.

It does make me feel afraid that one day my parents might pass on, and I might no longer get the opportunity to let them know that I love them.

Too often, we take things for granted and assume that everything will remain as is perpetually. Let’s face it, how often do we truly pause and think about the ‘what-ifs’ in the event where our loved ones pass on one day, and the things that we haven’t done today?

I certainly haven’t given it much thought until now, which frightens me. But it has also motivated me to become more open in expressing affection toward my parents.

Thinking about it, my mum’s birthday is coming in a week’s time. I think I’ll make it one of her most memorable birthdays. On top of the usual birthday cake and present, I’ll also let her know that I love her.