All images by Isaiah Chua for RICE Media unless stated otherwise.

An hour before their show, my friends from Thambi K Seaow—a satirical rock band with a cult following a decade deep—asked me to warm up the crowd before their set. I was honoured, especially since I’d be introducing them at a venue that, in just a handful of years, had gained its own cult status: Phil Studio.

As I tested the mic on stage, my “ok, can?” was met with a thumbs up by Phil himself. A middle-aged East Asian man whose eyes crinkle when he smiles, Phil comes across like your friendly neighbourhood uncle—unassuming and unflustered. He’s often helping behind the bar, brimming with an easy smile as upstart musicians cut their teeth on his stage.

ADVERTISEMENT

No way would I have guessed that this 50-something-year-old is a martial arts sensei with black belts across multiple disciplines. On top of having two master’s degrees and a PhD.

And on top of all that is Dr Phil’s eponymous studio. It’s impressive because Singapore hasn’t seen a privately owned venue champion local music with this kind of fervour and success in years.

Shouldering soaring rent while trying to keep ticket prices affordable is a precarious equation, and many independent gig venues like Gas Haus, Home Club, Decline, and more have shuttered under the weight of these odds.

International names like Left to Die, Massacre, Origami Angel, The Fall of Troy, and Plain White T’s have all graced Phil Studio. Local favourites like Amateur Takes Control, Carpet Golf, Caracal, Subsonic Eye, Marijannah, and many more have made their rounds on Phil’s stage.

There’s a reason why local artists gravitate to Phil Studio—this hassle-free, plug-and-play venue at the basement of Selegie shopping mall GR.iD is open to all genres and anyone who needs a stage. In a city where rising real estate prices are choking the independent performing arts scene, Phil Studio has been going strong for the past two years. Grew bigger, even.

Built on inclusivity rather than clout and profits, Phil Studio has become Singapore’s new cultural incubator where subcultures intersect—from Latin dancers to Indian classical musicians; from acoustic singer-songwriters to hardcore punks.

There are no barriers between artist and audience here, and accessible and well-equipped venues are hard to come by in Singapore. Spectrum looks like a nightclub, but can be quickly transformed into a professional concert venue.

So when artists bare their souls on Phil’s stage, they attract an assortment of spectators, especially Gen Z-ers who crave raw and real connections after the isolation of the Covid years.

ADVERTISEMENT

But Phil tells me he doesn’t just champion local musicians. He roots for comedians, martial artists, and all kinds of performers who’ve coloured his stage.

“When you’re on stage, you’re naked, with just your skills to save you,” he chuckles in a thick French accent.

This enigmatic, scholarly pugilist has a French last name, but prefers to go by ‘Phil’, so as to keep his personal life separate from the far-reaching impact that he’s making on Singapore’s independent music scene.

Who is Phil?

Although he’s managed to blend into the local populace for the past 15 years, Phil is actually of Korean and Spanish ancestry and was born in Aix-en-Provence, a city in southern France, in the 1970s.

ADVERTISEMENT

His parents had fled the Korean Peninsula during the tumult that followed the Korean War. Phil was raised in France, where he developed a passion for dissecting complexity, whether in physics or in art.

He began practising Judo at five and entered international competitions at 17, which was when he was awarded his first black belt. By 25, he had earned his second.

He would go on to clinch a first-degree black belt in Taekwondo, a fourth-degree black belt in Shinkyokushin (full contact) Karate, and a second-degree black belt in Shotokan Karate.

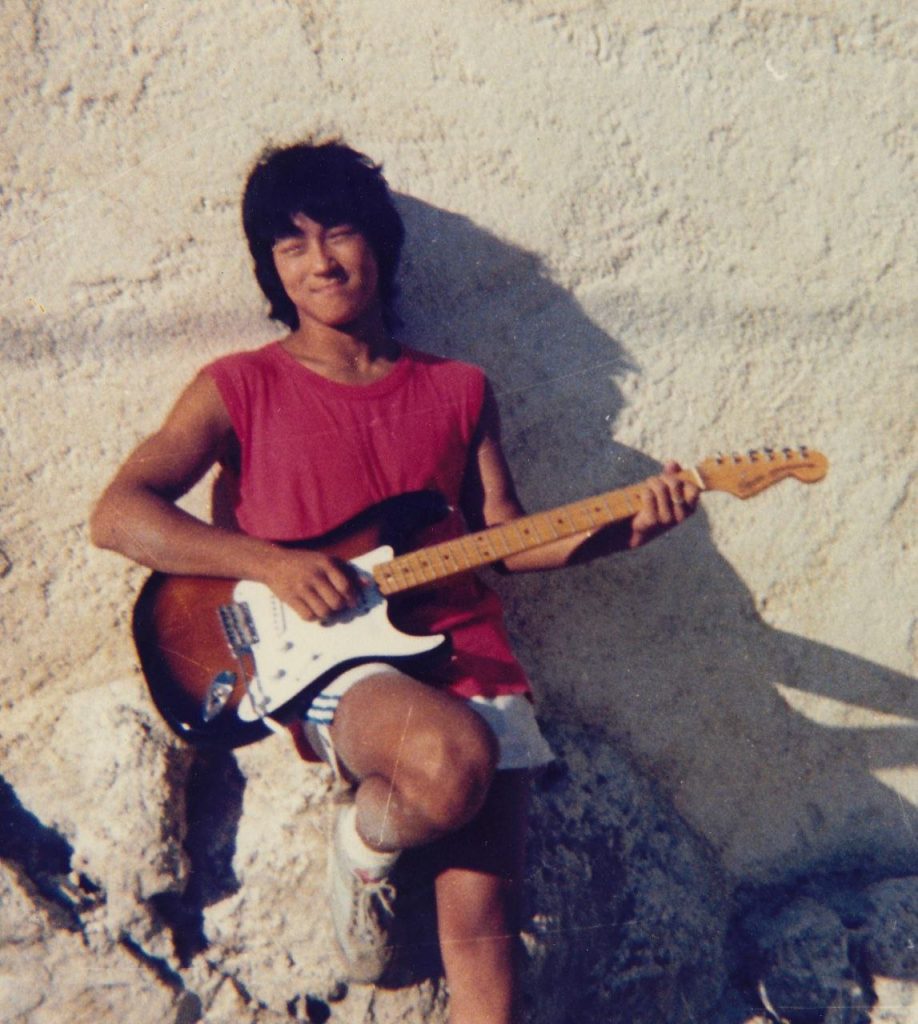

“I also learned to play guitar when I was a teenager, you know, to impress girls,” he laughs.

He holds a master’s in microelectronics, another in electrical engineering, and a PhD in semiconductor physics.

Besides teaching martial arts, he’s a corporate leader. He prefers not to name his day job, but you could say Phil is also a sensei of quantum mechanics.

“But first and foremost, I’m a family guy,” says Phil, whose 18-year-old son inherited his father’s knack for martial arts and music.

His resumé reads like something AI might conjure when asked to invent the perfect overachiever, but Phil wears it lightly. He’d rather shine a spotlight on others.

“Because we have too many talented artists in Singapore, and they deserve a platform where they can grow.”

Don’t be fooled by the warm grin, though. When he gets going, Phil speaks with the no-nonsense bark of a discipline master—enough to make even the scariest black metal vocalist seem tame.

Every time he raps a Coke can on the table for emphasis, my spine straightens involuntarily.

He doesn’t mince words, and that candour has ruffled feathers. Some creative egos have bristled at his blunt critiques. But even in conflict, his intent is clear: to push artists beyond comfort and into their full potential.

Perhaps, playing into the kindly Asian uncle stereotype helps others feel at ease. But behind that disarming presence is someone far more formidable—a catalyst who champions creativity, with the energy of someone half his age.

Phil’s Crucible

Phil moved to Singapore in 2010 as a laboratory director. He’s always worked in scientific research, and dedicates his free time to music and sharing his knowledge of karate. During the pandemic lockdowns, he built a karate dojo in his landed house to run small classes for kids and adults.

Eventually, he converted part of it into a jamming space for musician friends, constructing the studio himself, piece by piece.

“When the lockdown ended, I needed somewhere to store all the gear I’d collected,” he laughs.

And so he rented an 800-square-foot unit in Parklane Shopping Mall in 2023. “It was 99 per cent a karate dojo,” he recalls. But one night, while jamming with friends in front of the dojo mats, a thought struck him: This looks like a concert pit.

And with that spark, a new hybrid space was born.

By 2024, Phil moved to a space on the third level of High Street Centre, right across Parliament House. His vision had evolved from a casual jam space to a full-fledged performing arts venue.

After dark, once the building’s private schools and law firms shutter for the day, Phil Studio comes alive at night to draw in a very different crowd—underground musicians and the restless souls who trail after them.

Musicians came, yes. But so did comedians, DJs, dancers—anyone in need of a stage in a city starved of performance venues. The room was all sharp corners and low ceilings, never meant for a full-blown stage.

Not many, except Phil, would’ve thought of opening a gig venue within High Street Centre.

“The unit was small, its ceiling was low, the old building wasn’t well maintained, and it’s constantly under threat of en bloc,” recalls Phil, who began looking for better alternatives not long after moving in.

Nevertheless, Phil would host performances in his increasingly popular venue after work, night in and night out. Not just because he’s played music since childhood, but because he’s a pious devotee of the performing arts.

“You can’t bullshit when you perform,” he tells me, eyes gleaming.

“When you mess up on stage, people laugh. When you make a mistake in martial arts, you get hurt. No filters and no AI can save you when it’s just you, your art, and your audience.”

In early 2025, Phil moved again—this time to GR.iD, about a kilometre north of High Street Centre. The new spot is twice as big; its sound system rivals professional venues. But the soul of the space still hums like a Thai disco—unpretentious, unvarnished, and impossible to fake.

With the move came a new name: Spectrum by Phil Studio.

“‘Spectrum’ is all colours coming together,” he explains to me while sipping a whiskey coke near the entrance of his establishment.

It’s not just a fancy name—it’s a mission statement.

Phil is no stranger to Singapore’s art scene politics. He’s seen local performers shun each other over petty genre differences. He’s watched dancers gatekeep their shows and noticed musicians refusing to share bills.

And Phil is determined to pulverise the siloed mindsets local artists often retreat into. He slams his Coke can on the table again.

“I just want to break down the fucking barriers in the arts,” he says. “Let people come, plug in, and play.”

DIY or Die

Phil’s venue is in no way government-subsidised. He pays the rent, handles the logistics, and does all the mind-numbing paperwork—a defining trait of local bureaucracy—so that performers can just “plug in and play”.

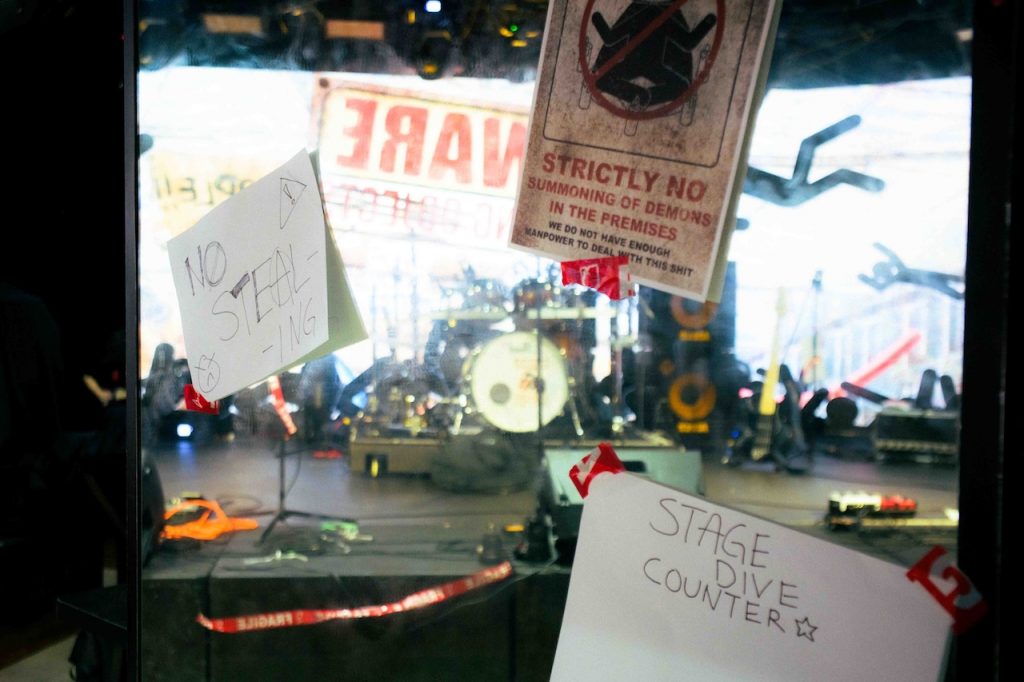

This is what Spectrum offers: a spacious pit, a well-equipped stage with a solid backline, an LED backdrop, and booking fees that won’t break the bank. And when you rent the space, you get Phil too—a very hands-on, very unflappable host who welcomes every kind of art with open arms.

And from what I learn, he’s shouldering everything on his own, including three full-time staff and several part-time staff on his payroll.

During his formative years in France’s pulsating gig scene, Phil was electrified by the raw passion and relentless drive of the country’s independent artists. It’s that same unwavering spirit he now hopes to stir in Singapore, where he dreams of an arts scene just as bold, hungry, and alive.

He speaks fondly of Le Plus Grand Cabaret du Monde, a French TV show that celebrated musicians, dancers, magicians, acrobats—“anyone pushing the boundaries of what humans are capable of”.

After every commercial break lay a new surprise, which kept a young Phil glued, dreaming of offering a stage to such radical diversity. Today, he’s grateful that he can provide refuge to a wide spectrum of creatives, through highs and lows.

Phil remains tight-lipped about margins—only that some nights make money, and some don’t. But unlike most, he doesn’t need the studio to put food on the table.

With other income streams and a steady, corporate job to provide for his family, he’s in a position to fund the space out of his own pocket, sheltered from the financial risks that usually keep others out.

“And it will never be about the money,” he affirms. “Overall, we are very solid and sustainable.”

Phil’s not one to complain, because he’s too busy creating a space where the next generation can fall and rise again.

While rents spiral out of control across the country, Spectrum thrives—booked solid nearly every night. Perhaps Phil has cracked the code. By opening his doors to everyone (from cha-cha dancers to cybergoths), he’s managed to build a sustainable business on one core belief: inclusivity.

Like the martial artist he is, Phil rises to challenges without hesitation. And he’s not afraid to challenge me either.

When I bring up Singapore’s ailing music scene, he snaps back: “Swee Lee has a huge store in Clarke Quay selling top-of-the-line equipment. If kids aren’t playing music anymore, then explain how Swee Lee is still in business.”

To Phil, the problem isn’t a lack of talent, but comfort.

“If we want to develop the next generation of artists—and Singapore has so many—they need opportunities, equipment and affordable venues.” And this is Phil’s humble yet priceless contribution.

However, Phil points out: “People want results without enduring suffering.”

Making music in Singapore isn’t a bed of roses—playing to thin crowds, paying for and carrying one’s own equipment, receiving scarce bookings, and getting paid in exposure are all part of a young musician’s baptism.

Rather than rise to the occasion, Phil laments that too many young musicians give up and move on after failing to catch their big break.

“But I’ve also seen the ones who’ve paid their dues, like [all-female alt rock band] Taledrops. They weren’t very well-known at first. Now, they have a sizeable fanbase and they’re crushing it.”

He cheers and hollers when upstart bands like Cactus Cactus take his stage.

Even the CB Dogs—infamous for their crude language and schoolboy humour—have earned his respect. “They just played here for the fifth time. They’re living proof that consistent hard work leads to success.”

Ultimately, Phil just wants to provide a soapbox for artists, where they can earn their metaphorical black belts and foster a sense of community while at it.

“Phil Studio is the new Substation! It’s a haven for the underground, for all kinds of unique ventures—modern dance, stand-up comedy, even martial arts,” says Petir Mamat of the InKorruptibles, one of many local bands who’ve found a home here.

Electronic musician JY Ang, aka Microchip Terror, also sings Phil’s praises: “I’m incredibly grateful for Phil’s support—and his LED wall, which let me display animations live for the first time.”

One-man band Cronkite Satellite shares how Phil welcomed his eclectic, cross-genre sound: “Phil always has a smile on his face and this genuine desire to help the music scene. He’s supported all my musical incarnations, and so many other artists from all genres.”

Phil is deeply touched by the love the scene has shown in return. But ever modest, he brushes off praise like he’s just another cog in the wheel—moved simply by the power of art.

“People flock to live music venues even if the speakers aren’t perfect,” he reflects.

“We perform or we watch, because it makes us feel something. It makes us dance, cry. It makes us human.”

Phil-ing a Hunger

Phil tells me he has nothing left to prove, but this space, these nights, the ringing feedback and calloused fingers are how he chooses to give back.

Spectrum by Phil Studio has become a sanctuary for unfiltered artistry. And Phil, with his quiet intensity, guards it, not for glory, but because he simply must.

And somehow, that choice has built something larger than any one person. Spectrum by Phil Studio isn’t just a venue; it’s a living, breathing argument for why physical spaces still matter.

“In this age of deepfakes and massive editing, the room for human artists is shrinking,” shares Phil of a worry that frequently crosses his mind.

“We want to provide affordable venues where artists can showcase their art and meet their fans. I think that’s especially important now, when increasing costs of living are convincing people to stay home and stream their entertainment.”

Within Spectrum’s walls, it’s obvious from the grins, the applause, the moshing and the occasional music scene drama. The act of showing up, for a gig and for each other, is revolutionary in a world constantly urging us to tune out.

At a time when creativity is filtered, monetised, and optimised to death, Phil’s stubborn refusal to play by those rules is as punk rock as it gets. He’s holding space for noise, for failure, for raw, awkward beauty.

“When fingers bleed into guitar strings, muscles pound on drum skins, I know that no AI will ever replace that.”

Where others see a basement, he sees a proving ground. An arena where audiences confer musicians their black belts, and a dojo that nurtures community, not ‘content creation’.

And maybe that’s the legacy he’s carving. The echoes left behind when the last chord rings out, and someone in the back row realises they’ve finally found their people.