All photos by Isaiah Chua for RICE Media unless otherwise stated.

Being a twin in Singapore means living life in constant echo. It can be as confusing as it is comforting; a constant negotiation of selfhood. Throughout their whole lives in a system that loves to measure and label, they’ll always have someone to be compared to, for better or for worse.

In a society that prizes uniformity, growing up with a twin turns the search for a distinct personal identity into a daily puzzle. How does one find oneself when the world constantly compares you to someone who looks, sounds, and sometimes even thinks exactly like you?

Four pairs of Singaporean twins reflect on what it’s like to grow up shadowed and mirrored—and how they’ve carved out individuality. In this instalment of our photo essay mini-series Twin Echoes, brothers Shaun and Kern Lee open up about how they’ve navigated their own life choices away from each other.

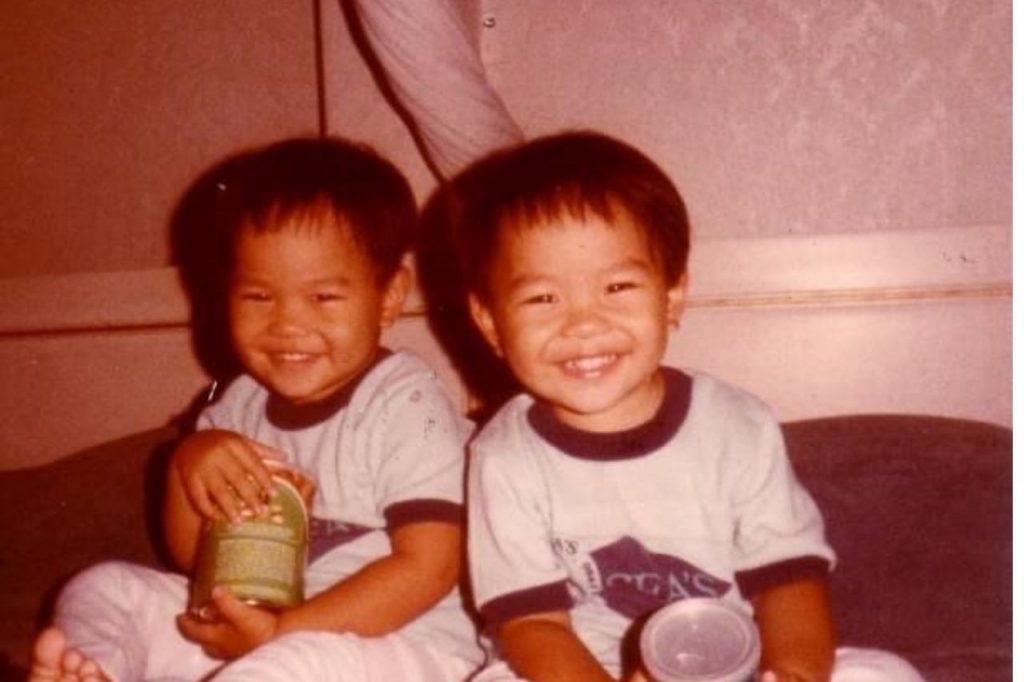

Shaun & Kern Lee, 45

Identical Twins

Kern: We’re the best of friends. Even in the army during National Service, when we weren’t in the same platoon, we’d call each other every day. When I got married and he stayed single, we’d still talk to each other regularly, even on my honeymoon. We know each other’s ins and outs.

Shaun: I’d say he’s my best friend too. He knows everything about me, and he’s a much more outgoing person than I am.

Kern: I can make friends anywhere and very easily. For instance, when it came to sports and activities, I was always the one to engage with other people, and then he’d join in. He’s more of an ambivert. When he’s with his friends, he’s very boisterous, usually the gregarious one in the group. But normally, he’s quiet.

Shaun: Growing up, it was natural for us not to have any differences. We also never really felt such an intense sense of competition between us to the point that we’d hate each other. But my brother’s definitely more laid back, and I’m more competitive.

Kern: Our parents tried to make it very fair for us, so if we were interested in different things, they would give us opportunities to explore them on our own.

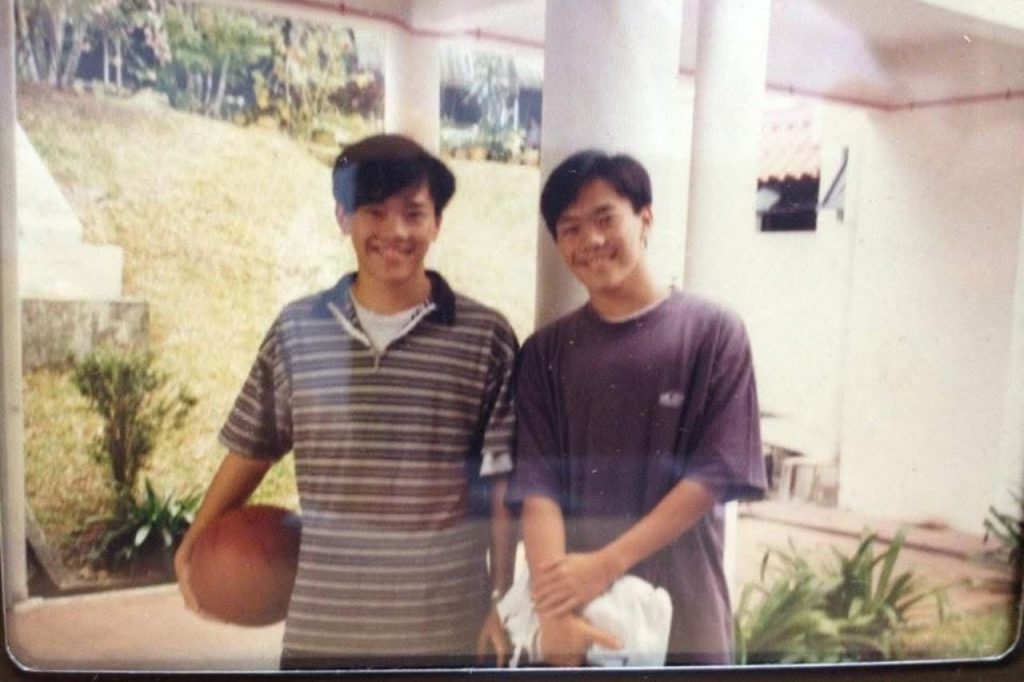

But we were very interested in sports. We were always grouped together in teams. However, when we were 17, we were put on different basketball teams. That was the first and only time we were separated, which created some tension between us.

That was a defining moment for me because from that point on, it was the first time we made friends independently.

Family and friends would love to compare us, for example, in terms of academics. While we had our differences, they’d still want us to maintain a certain level of similarity, such as how we dressed.

And when we grew up and wanted to become our own individuals, they questioned that a lot.

Shaun: Our mum actually loved to dress the two of us in the same clothes, so that was a little bit of a problem—we couldn’t share, and that became an issue. We always had two of the same things, never our own.

Oh, and we both have dyslexia, even though mine is a little worse than his.

I mean, we attended the same schools, served in the army together, and graduated from the same university. Psychologically, as you get older, sharing many similarities becomes a challenge because you want to establish your own identity.

Kern: When we started attending an international school, there was a 180° switch. Suddenly, they put us in different classes, told us to find our own friends and discover our own interests. But it was weird—we still signed up for the same activities, like we were telepathically connected.

It was hard because we felt like we never had our own identity. For example, I’d tell my friends stories and refer to myself as ‘we’ because I naturally associated myself with my brother.

But I think the turning point was when I got married. Life happened, and I got kids. He continued his single life and made more friends.

Our relationship still stayed strong because he’d introduce his friends to me along the way, and his friends would become my friends. But we’d live separate lives.

Kern: When we applied to universities after the army, we were accepted into 98 percent of the same schools. Although he had one university in mind, which he really wanted to attend—it was one of the top schools. That was the school that I didn’t get into, and despite appealing for the spot, they didn’t yield.

Shaun: So I chose to go to the same school as him.

Kern: But throughout the first semester, he complained, saying I was holding him back. We ended up confronting each other.

I remember that when we finished dinner at the dining hall, I confronted him, saying that we had both agreed to attend the same university, be each other’s roommate, and so on. We both knew that we’re stronger together than separated.

I told him that if he wanted to go, he was free to do so. It was his life. And I think having this confrontation helped him deal with his sentiments as well.

Shaun: Attending that school was more of a culture shock for me personally. The difference between American schools and Singaporean ones made it difficult to adjust.

We just needed that one conversation at dinner to really change my perspective on the school and our situation.

Kern: My brother just got engaged and is going to be married, but because my brother stayed single for so long, he actually took on the role of the older son in our family. He stayed back and took care of my elderly parents as I had my own family to start and care for.

Shaun: I took it on myself without asking anyone or needing anybody’s help. But I think as time went on, I felt quite mentally fatigued because I was bearing a lot of responsibilities by myself.

But I’m glad that my brother shared the workload with me. He buys food for my parents and the groceries, so I’m not so burdened by it.

Kern: There was a lot of guilt that I felt, and the feeling that I was burdening him. But we naturally compensated for each other when we had the time.

We try to work as a team now.