This story is part of our photo-essay miniseries, Unexpected Adulthood.

Adulthood doesn’t come with age—it hits when life leaves you no choice. In this series, Singaporeans revisit the moments that forced them to grow up, ready or not.

All images by Justin Tan for RICE Media unless stated otherwise.

Graduation’s over, my mid-20s are here, and I’m left staring down the big question: What does being a fully-fledged adult actually look like? How will I know I’m officially an adult in Singapore?

But what I do know now is that adulthood doesn’t arrive with a grand declaration, and its arrival looks different for everyone. It could be as simple as buying your first personal insurance plan, or as major as applying for a BTO flat.

Not everyone gets the luxury of easing into it—sometimes, the moment you’re forced to grow up comes long before you’re ready.

For Jess Lim, adulthood arrived not with a milestone, but with loss. Both her parents passed away in 2014 when she was just 20, at the start of her third year at the National University of Singapore. She was their only child, studying in Singapore while they remained based in Kuala Lumpur.

In 2013, Jess’ diabetic father had suffered from an infection after a kidney transplant, which led to a stroke and partial paralysis. Her mother would eventually suffer from a stroke eight months later, after taking on the added financial and emotional toll involved with the intensive care that her father required.

“From studying, suddenly it was about survival. Can I even finish university fast enough to start working and somehow support myself and my parents?” she recalls.

Jess was suddenly alone to bear the heavy responsibilities. Her mother had to be put on life support, while her father remained bedridden and paralysed.

Not long after, Jess’ father passed. With doctors confirming that her mum was brain dead, Jess made the difficult decision to pull the plug on the life support a day later. All of this before even graduating from university.

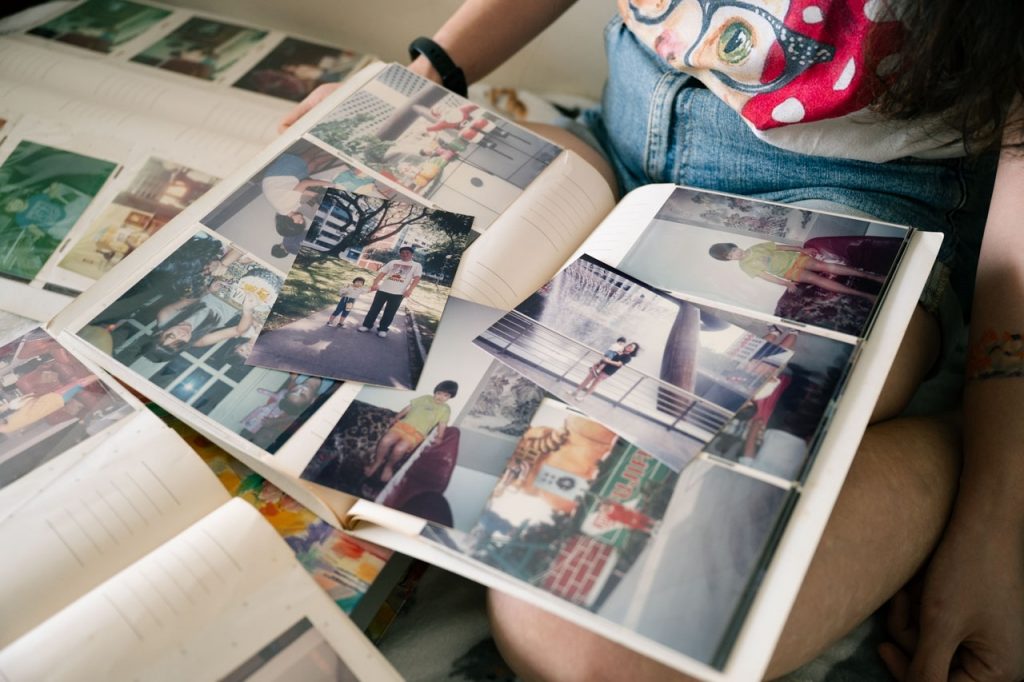

Now 31 and working as an accountant, Jess invites me to her 3-room flat in Clementi, which she inherited after her parents passed, to share her calamitous coming-of-age moment.

Could you walk us through the series of events that happened leading up to their passing?

[My dad] had to have a kidney transplant, but it didn’t work. It kept on giving problems, and then he got a really bad infection. He got intubated because his oxygen levels plummeted, and then during the intubation, he had his first stroke in December 2013.

He stabilised soon after, but he was half-paralysed and couldn’t talk. My mum took care of him for eight months, and I think that put a lot of stress on her.

My dad’s treatment became really expensive because my mum had two full-time nurses looking after him. He also needed immunosuppressants for his kidneys.

When I figured out how much that all cost and then compared it to my mum’s salary, I realised why she was so stressed—his treatment was wiping out more than what she was earning. Then my mum’s stroke happened on August 19th, 2014.

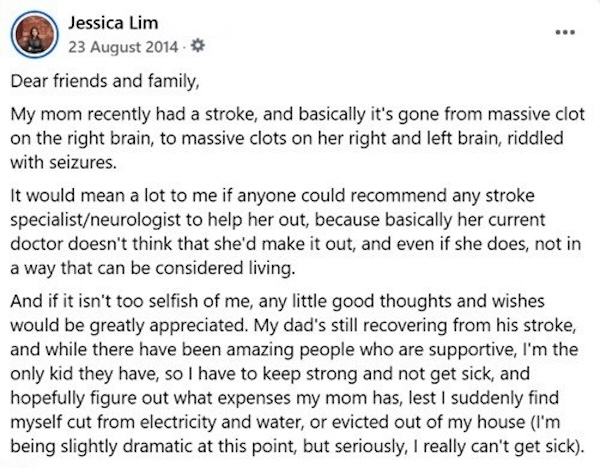

I got a call from her company’s HR department telling me that [my mother] had a stroke. Both of my parents were working in Malaysia at the time, so when that call arrived, I had to drop everything and book the first available bus from Singapore to Kuala Lumpur.

I was on my own at the time. My paternal uncle drove up to KL to be with me a few days later.

And then my mum had her second stroke. That’s when the doctor told me that she was officially brain-dead. There was nothing else they could do.

Since she was on life support, it was only a matter of when I would turn it off. By the end of August, I had already decided that I would end it on September 3rd.

I think at the time my dad understood certain words, so I informed him about my mum. I had to tell him that I didn’t think she was going to make it.

On the first of September, he had a chest infection and then suffered a second stroke. My dad passed away the day before we pulled the plug on my mum.

I had their funerals on the same day. The funeral was arranged for my mum, but then my dad passed as well. We decided they could have a joint one.

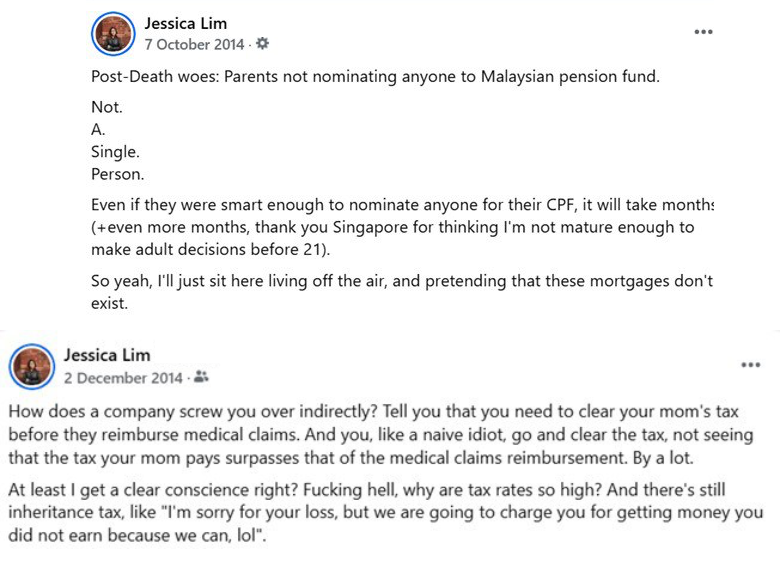

I was just looking back at what I wrote, because I wrote a lot back then. I forgot how stressed I was with studies, and final year [in university], and looking for a job. On top of all that, I was dealing with a lot of the legal stuff after their deaths.

That was quite a crisis to undergo for a 20-year-old. Did the experience change the way you saw yourself?

In times of crisis, I realised the kind of person I am—I just act. There was no space for sadness, no room to think about what six months down the road might look like.

All I can focus on are the concrete things and what I can do in this moment.

What were some immediate concerns that you had to navigate?

I was thinking: Where do I live? Their home in Malaysia was still under mortgage, and there wasn’t insurance on the mortgage—so I had to pay off the mortgage. Otherwise, the bank would repossess the house. Where would I get this money from?

I also ended up having to pay more in taxes than what I got [from her company’s insurance payout]. Her company [in Malaysia] said that before they could release the money to me, they needed to make sure that my mum didn’t have any debt in taxes.

Once that was sorted out, I went straight back to school. I took a Leave of Absence for a semester away from school. I think it took like a full good year or so to even just settle all the stuff related to my parents’ deaths.

This is the part they don’t prepare you for adulthood—dealing with so much paperwork and legal issues.

Mum and Dad had their personal insurance in Singapore as well, but because I was under 21, I had trouble getting started with the process for their insurance claim. They put each other as the beneficiaries, because they got the policy before I was born, and they never updated it. So I had to wait for the will to be sorted out because I had no right to get their insurance payout.

It was the same thing with their CPF accounts. When anyone passes, the funds will be released to their nominated beneficiaries. I was not a nominated beneficiary in their accounts. I had to wait until the will got sorted out.

Because they passed away overseas, I also had to inform the Immigration and Checkpoints Authority about their deaths before any processes could kick off.

Were there people around to support you during that period of time?

There was a message that I posted on Facebook—I was so desperate.

I wrote that my mum’s doctor told me her prognosis, and asked if anyone knew of any doctor I could go to for a second opinion. And this guy, a friend of a friend, just reached out and was like: “My dad’s a neurosurgeon, if you want a second opinion, just give me a photo and I can try to ask him for a second opinion”.

That was really nice.

His dad helped look at the photos of the MRI. But his second opinion confirmed the prognosis: there was no brain left.

There was only a bit left at the back, and the back apparently just controls bodily functions like breathing and heartbeat.

Relatives were there for me, too. My mum was quite estranged from her side of the family, but when my aunt heard about what happened to my mum, I think she quit her job and flew from New Zealand to stay in Malaysia with me for a while.

I lived so many years outside of Singapore, so most of my interactions with my relatives have always been only at major holidays, like Christmas or Chinese New Year. But I feel they made it a point to invite me to family gatherings as well.

After all the dust settled, I think most of it returned to the status quo—friends didn’t really treat me differently, and my relatives didn’t really treat me differently either. Which was nice, because I don’t want to be pitied as well.

To be honest, I’ve forgotten much of what I felt in that moment. I think I’ve just gotten very good at burying my emotions. Strangely, it was easier to talk about my parents right after they passed—I could speak about them stone cold, like it didn’t affect me.

I find it harder as time goes on. I’m not entirely sure why, but I think it’s because the emotions are now more present when I’m not in a fight or flight mode.

How did that change your views on life after that?

I think it shifted my perspective on life a little—when you’re young, death doesn’t usually feel that close.

But after going through that, I set a rule for myself: if work, or anything else, ever makes me feel as stressed as I did when I was dealing with my parents’ deaths, I have to take control and say no. Because really, what could possibly be worse than losing your parents?

I guess I grew more confident? Back then, I was barely an adult, and when I saw how the adults were handling things and treating me, I felt like I couldn’t trust them.

That’s when I took things into my own hands, and I had to do a lot of it on my own. And if I got through that fine on my own, I can get through anything.

When I started work in auditing, I got super stressed. I was OT-ing every night. Clients were stressful, bosses were stressful. I felt out of it—I was getting so little sleep. My friends saw how stressed I was.

Eventually, I learned not to let my work ever dominate my personal time. No matter how much the company might appreciate your efforts, you can’t get your life back.

What did that experience teach you about what it really means to be an adult?

Adulthood, to me, means finally being able to focus on myself without anyone’s opinions shaping how I live my life.

Your parents always tell you what to do, right? And whether or not you agree, you usually just go along with it.

But after they passed, I hit an existential crisis: if my choices—what I study, the job I take—are no longer dictated by them, then what do I really want to do?

My relationship with my parents was strained because I was an only child. A lot of pressure and expectations were placed on me. I’ll be honest—six months to a year after they passed, I had nightmares of them coming back to life just to express their disappointment in me.

Life kept moving. The insurance payout eventually came through, along with my parents’ personal savings. It was nowhere near FIRE money, but it was comfortable. There’s a lot more control now. I don’t need to work for the sake of working, but because I enjoy it.

Being an adult means I get to make decisions for myself now, without judgment. Right or wrong, those choices are mine alone.

If you could say something to your younger self then, what would it be?

I would tell her to be less hard on herself. All the fears she has about the future works out in the end.

That, and don’t cheap out on things.