RICE does not endorse any political party in Singapore. Refer to our GE2025 content coverage policy for details.

Top image: Stephanie Lee / RICE Media

“Wait… does that mean I can’t vote?” our 23-year-old intern mutters, half to herself, as she watches Minister of State for Home Affairs Muhammad Faishal Ibrahim deliver a victory speech on Nomination Day.

It would’ve been her first time at the ballot box. Now, like her neighbours, she’ll have to wait another five years.

ADVERTISEMENT

Marine Parade–Braddell Heights GRC will go uncontested in GE2025. No rallies, no debate, no flyers in the mail. Just a quiet default—not because voters weren’t interested, but because no opposing party showed up.

The Workers’ Party, citing redrawn boundaries and limited resources, made the call not to contest this year despite campaigning in Marine Parade since GE2015. Strategically, it made sense. Focus on winnable constituencies. Maximise impact. Play to win.

But when politics becomes a numbers game, who loses?

Bounded Rationality

Of course, no opposition party wants a walkover. And few could’ve predicted how things would unfold.

At the heart of it is a perennial feature of Singapore’s electoral system: the shifting of boundaries. They shift with each election—sometimes subtly, sometimes drastically. Neighbourhoods get reshuffled; candidates disappear or reappear elsewhere; residents find themselves reassigned like pieces on a board.

Redrawn every election cycle, often with meagre explanation, these changes don’t just affect maps. They affect momentum, memory, and morale.

Parties understandably adapt with each redrawing. They withdraw, reallocate, and prioritise.

A party can spend years pounding pavements, building trust, showing face—only to have the map pulled out from under them. Volunteers scatter. Residents get shuffled into unfamiliar constituencies. Years of work gone with a new imaginary line on a map.

That’s the subtext behind the explanation for why the Workers’ Party didn’t turn up for Marine Parade this time around.

ADVERTISEMENT

In short: the ground they knew isn’t the same anymore. The Marine Parade they campaigned in for years has been reconfigured. Parts of it—where they’ve done the work—have been redrawn into other GRCs. And parts they’ve barely touched, like the areas from the former MacPherson SMC, now make up this new electoral Frankenstein.

WP has taken a stance: this new version of Marine Parade isn’t exactly the same one they’ve been walking. This is new terrain. And with limited resources, would it be wise to parachute a team into unfamiliar ground just to show up?

It’s a risky move, even without the chess moves we’re seeing from the ruling party—where key office holders get shifted into battleground wards to tip the scales. We saw it in 2020, when former DPM Heng Swee Keat was abruptly pulled to run in East Coast. We’re seeing it now with DPM Gan Kim Yong’s pivot to Punggol.

With that in mind comes the strategy to keep cards close to the chest. Unfortunately, all that culminated in the residents of Marine Parade-Braddell Heights GRC not having the chance to make a choice.

The Playing Field

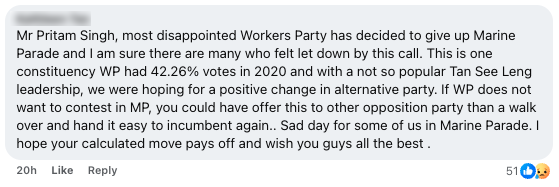

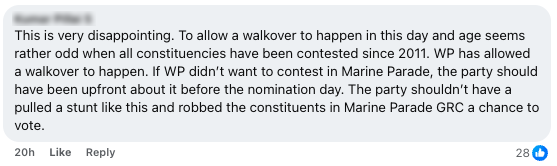

Yes, politics is for the people. The disappointment voters feel when there’s no contest is real and very valid. To watch Nomination Day unfold and discover there will be no debate, no choice, no engagement—it feels like something was stolen.

In a high-stakes environment where opposition parties are already stretched thin, this is the cruel math they’re forced to do: focus on where they’ve had time to build real presence, or risk burning out good people in a territory they haven’t made strong inroads in.

When walkovers happen, though, it reverberates among constituents. They face the absence of contest, of public debate, of even the chance to engage in a healthy democracy. It erodes the feeling that they were meant to have one in the first place.

Worse, it chips away at a deeper emotional truth. When no one shows up to make a case, voters can’t help but wonder—was my vote ever meant to matter?

That feeling lingers not just as disappointment, but as a kind of soft disenfranchisement. The quiet sense that your neighbourhood wasn’t worth the fight.

And while this strategy may serve parties in the short run, it leaves voters with long-term scars: cynicism, detachment, and the creeping belief that politics happens with or without them.

No doubt, WP will face a Sisyphean task of regaining the trust of Marine Parade’s residents over the next five years. It might even take longer for them to finally be in a place where they can confidently contest again in Marine Parade.

Again, feelings of disappointment are valid. Yes, they might not get to vote this time. But that absence could mean voters elsewhere now have stronger candidates to choose from. It could also mean a higher chance for these candidates to actually make it into Parliament.

Because when the system itself introduces this much unpredictability every time boundaries warp, is it any surprise we end up with Nomination Day curveballs? With walkovers that blindside even the most loyal supporters who turned up in good faith?

Until we properly address how shifting electoral boundaries continue to disrupt political engagement on both sides, we’ll keep having these moments of confusion and frustration every time the General Elections roll around.

Because when residents feel confused and parties feel cornered, no one really wins.