One of the greatest myths of sex work is that it isn’t work. In a recent blog post, Singaporean social escort Rebecca Lee, better known as Risqué Rebecca, lambasted an article in CLEO Magazine that sensationalised the profession.

In Rebecca’s words: “… we all have bad days and good days at work. There’s nothing to “be real” about. I really enjoy what I do, but just because it isn’t “fun” or “enjoyable” all the time doesn’t diminish this as a profession. For example, a good day for you might be to use escorts as an inspiration for your new article while simultaneously reinforcing decades and centuries of negative assumptions!”

Likewise for most laymen, we tend to think only of the money and services transacted between client and worker. But much like any other industry in Singapore, sex work accounts for a large amount of revenue that goes eventually to building the country’s economy.

When we sat down with Rebecca and Scarlet (another social escort) to map out the entire financial ecosystem surrounding this industry, Scarlet related how an escort colleague turned to this trade to pay off a loan for her HDB flat. A burden of this sort, undoubtedly, is something most Singaporeans can relate to.

Some Basic Numbers

Before Rebecca transitioned into social escorting, she was a sugar baby. For those unfamiliar with the term, sugar babies are generally individuals who receive an allowance from a sugar ‘daddy’ or ‘mummy’ in exchange for companionship and (sometimes but not always) physical intimacy.

During this time, she received S$2000 a month for between 16 to 20 hours a week of companionship. That’s about S$25 to S$30 an hour.

This might sound like a fair bit of money, but it doesn’t account for the additional time that these arrangements often entail. Rebecca tells us about a client who was “emotionally high maintenance,” who would text her throughout the week seeking consolation that what he was doing wasn’t wrong. She was not compensated for this emotional labour, which was never supposed to be part of their arrangement.

Today, Rebecca is no longer a sugar baby. As a social escort, she charges S$450 for an hour of her companionship. Her time is still money, and while her rates vary across arrangements that range from 1-hour sessions to 12 hour ones, these transactions involve other costs that aren’t usually accounted for in our collective imagination.

Clients foot the bill for hotel rooms, and in Scarlet’s case, for transport as well. Rebecca is primarily a dinner date companion, and only dines at upscale restaurants because they offer discretion. As an escort, being a fun, witty and knowledgeable confidante comprises the central part work.

This aspect of their work becomes clear when Scarlet tells us about how she has spent money on both language courses and a wine appreciation class. In total, these have set her back about S$1000. A colleague of hers has even gone so far as to pay S$15,000 for plastic surgery. Essentially, these are investments that help to justify better rates.

While Scarlet and Rebecca are independent social escorts, there are many girls out there who aren’t. A lot of them are featured on sites like Backpage and SammyBoy by agents or agencies, who handle their administrative work and serve as the main point of contact for girls and clients alike. Agents usually take a 30-50% cut of what they make, so a girl who charges $1000 an hour really only takes home $500.

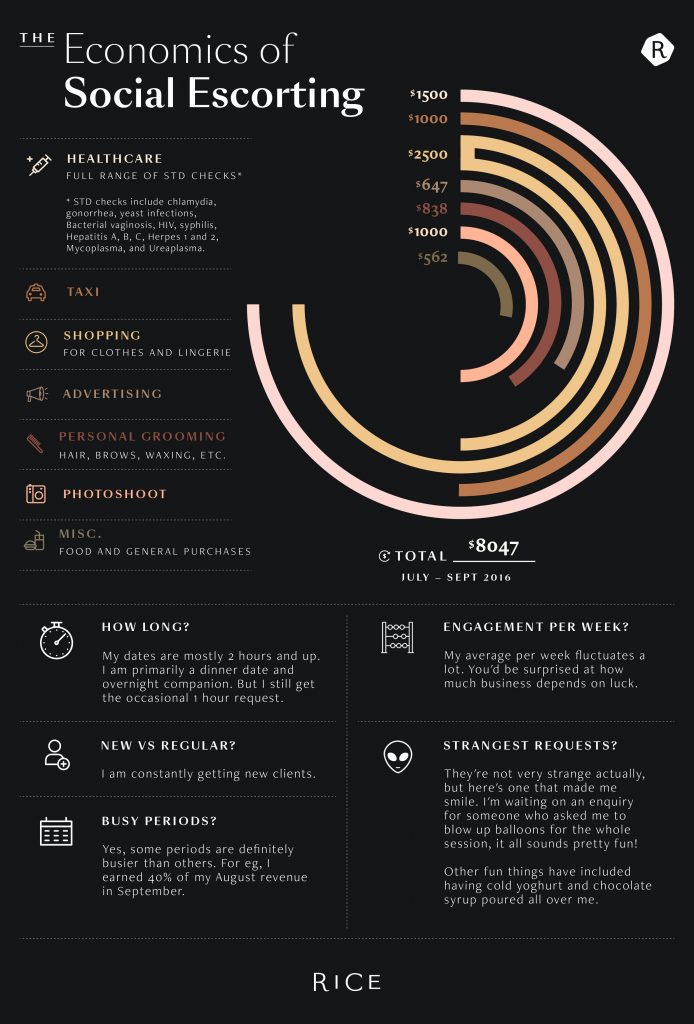

For a lot of these social escorts, agent fees are just one headache. There is the cost of personal grooming, advertising and health checkups. In the above infographic, a detailed breakdown has been illustrated of what it costs Rebecca just to be a social escort.

Scarlet estimates that about 200 to 300 social escorts enter and leave the industry every month.

The S$2682 she forks out every month goes towards Singapore’s retail, tech, creative, transport and medical industries. In the course of her work, the hospitality industry benefits as well; her dinner dates are no different from the business lunches that corporate executives partake in on a regular basis.

Scarlet estimates that about 200 to 300 social escorts enter and leave the industry every month, which gives us a pretty good idea of how much money social escorts alone generate for Singapore’s economy. For the two of them, a typical (approximately) 20-hour work month might net them about S$9000.

Some of these girls are in it for the money, but there are also those who are trying to pay off debts. There are education and housing loans, and some girls do this to be able to eventually launch their own businesses.

If the implications of these facts aren’t clear, here’s one way to look at it:

Girls who are able to afford their degrees then become able to pursue better, higher-value careers. Those who start businesses end up creating jobs. Those who manage to pay off their loans are then able to exercise their financial independence via spending in other areas.

This isn’t how everyone chooses to do these things, but it’s certainly one way to do it.

Opportunity Cost

Scarlet and Rebecca come from distinctly different family backgrounds. Scarlet juggles multiple gigs in events and social work on top of escorting and being a full-time student. She tells us that because of her family situation, she has no choice but to pay her own way through a private university.

Rebecca, on the other hand, doesn’t have to worry about her school fees at all. “I admit that I come from a privileged background,” she says, “Pretty much everything is paid for so I’m just doing this for fun.” On her profile on her website, she writes that, “Growing up, I dabbled in sports, namely swimming, fencing and squash.”

A little later, she adds, “Eventually I want my money to go into an investment portfolio.”

Despite these differences in personal ambition, there is one thing both ladies can agree on: social escorting is about capitalising on their youth. Along with this justification is Scarlet’s assertion that “Everything is all about profit-loss statements.”

Both Scarlet and Rebecca are only 20 this year, and are in the prime of their youth. Their rates are on the higher side, though they tell us that older social escorts (those in their 40s) command rates that go as low as S$200-S$250 an hour.

This is the predicament that a lot of escorts who lack formal education or business savvy often end up in. Many enter the industry thinking they will not do it for long, but it can eventually become a challenge to leave. Over time, it becomes the only thing they know how to do.

Because ‘Social Escort’ isn’t exactly something you can put on a resumé, a lot of escorts eventually end up trapped because the hourly compensation of unskilled jobs can seem paltry in comparison to what they make. For these workers, to be a social escort is to risk taking on a future of few alternatives.

We are more likely to judge a sex worker for soliciting than we are a client for engaging such services.

When our conversation with Scarlet and Rebecca turns to that of relationships, we get a sense of how escort work can go on to colour one’s relationship with money. Scarlet insists she would only date someone who pays for everything. On this point, Rebecca wavers, but ultimately emphasises that she still expects to be compensated for her time (if not in a tangible way, then in the intangible form of undying loyalty).

With escort-client relationships, the financial dimension takes centre-stage. Scarlet admits that she worries about how this might affect how she looks at love. Because everything is so rigidly measured in dollars and sense, it can be hard to see love for what it is—something that should ultimately transcend cost-benefit analyses.

Rebecca, on the other hand, is a romantic at heart. She is not jaded at all, and writes in her response to CLEO that “We are very much able to love and BE loved.” It has nothing to do with being a gold-digger and being able to afford the latest, trendy luxuries.

They acknowledge that they have been pampered by their work, and this has shaped their expectations of how men should behave in a romantic context.

We have a term for such dangers: occupational hazards.

Educators often struggle with mental health issues, and construction workers occasionally encounter falling objects. Whether we like it or not, this is no different.

The Only Problem Is,

We are more likely to judge a sex worker for soliciting than we are a client for engaging such services. We forget that it’s only because of demand that the supply exists. We don’t realise that the stigma attached to sex work is a direct result of a culture of victim blaming and slut shaming.

The fact is that it exists. To contemplate whether sex work is good for society is to perhaps ask the wrong question. When it is stigmatised, it creates an often dangerous environment for workers. Legislation in Singapore criminalises soliciting, which means that sex workers often cannot go to the police when clients turn abusive.

With this deconstruction of the financial workings of social escorting, this story aims only to do one thing: to illustrate how sex work is as deserving of the dignity as any other occupation.

It is one thing to disapprove of it, but to deny the people who carry this industry their rights is something else. For this to change, society will need to start by re-thinking how it looks at sex work.