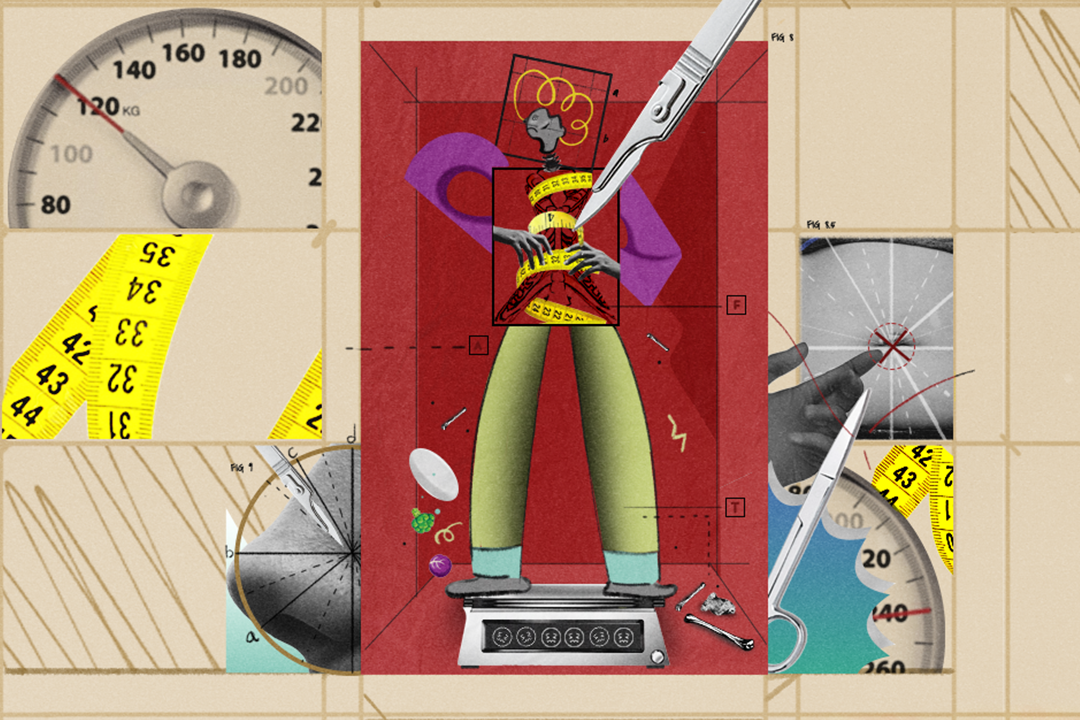

Top image: @iandanmari

I recently met an anorexic patient who shared her story with me. She was a few years older than me, skinnier than me, and shared a similar educational background and story as me. She reminds me of someone I could have easily been, and made me recall my fraught and estranged relationship with food over the many years.

My personal account is only one story, and should not be equated to anyone else’s experience. Many patients with clinically diagnosed eating disorders struggle with body image to a more debilitating and incapacitating extent.

As a little girl

I remember staring at my body as a little girl in the full-length mirror, my mother behind me, bunning my hair with bobby pins. I marvelled at the contour of my ribs beneath my primrose leotard—how they scalloped and curved down to form a cage, the pliable lungs they protected timing my breaths.

I remember sucking in my stomach tighter to make my ribs more pronounced. “I have a birdcage inside me!” I sang as I looked up at my mother. Turning back to the mirror, I traced the lower edge of my ribs, counting the number of stands I could offer flyover birds to perch on.

Even as a little girl, I had these ingrained notions of what a body should look like, how I wanted my body to look like.

How I had formed them, I can no longer recall. There was no defining incident that seeded these preoccupations. Instead, it was a series of subtle cues and references I picked up and internalised as truth, which I further fed and embellished with my interpretations. These repeated motifs reinforced my views on body image, which I then assimilated and acted on. In retrospect, most of these messages were unassumingly innocuous, but I was susceptible as a child, impressionable and eager to please.

Growing up, the girls in the cartoons I enjoyed somehow all had inverted pyramids for bodies, their torsos the thinnest parts of them. The girls in W.I.T.C.H. and Winx Club entranced me: they were powerful and magical, an image of who I wanted to become. Nevertheless, no matter how hard I tried, biology ordained I could not develop wings overnight. When I fashioned my T-shirt into a tank top with its lower end tied in a knot, I could never look as good; I could see my stomach bulge.

It never occurred to me that the girls on screen could be admired for their personalities and talents as well—they were resolute in their fight against the villains, beautiful in their heart for others. I conflated the girls’ worth with their appearance, neglecting the morals and lessons embedded within the episodes. I took everything I saw at face value, unable to see beyond the veneer.

In childhood, cruelty manifests in silence

Another incident I recall vividly: fat-shaming in primary school.

There was a classmate of mine who ran a little slower than the rest of us. Our school did not have a full-length track, so we jogged around an L-shaped asphalt road that looped back on itself. In every physical exercise class, he would be at the tail end of the troop, trailing behind the rest of us. We would watch him circle the bend as we started on our new laps, sniggling amongst ourselves at how his fats jiggled as he ran, joking he might have been an inflated balloon if only he was lighter.

I was not the one propelling the mean jokes, but I laughed along, complicit. In childhood, cruelty can also manifest in silence, in acts of omission.

As I grew up, societal standards surrounding body image became even more stark and poignant. They bombarded me everywhere I looked: in the TV shows I watched, the magazines I flipped through, bus stop advertisements by the roadside, conversations in school with friends. And in the mirror, when I looked at myself. Skinny was beautiful. Skinny was coveted.

My eating patterns became more rigid and restrictive. There were certain foods I could eat; there were certain foods I could not eat, which were out of bounds, taboo, no-no. I ceased to find pure joy in eating, pleasure unadulterated, in the simplest sense. A sense of guilt and awareness now sullied everything—the extra calories I was consuming, how another piece of bread was one too many. I no longer craved ice cream or chocolate like I used to, things I instinctively reached for previously for comfort. I was conscious that a slip of the lips meant another love handle around the hips, another hour on the treadmill.

My newfound food choices left me with the strangest mix of grief and relief. I imagined eating less of that creamy, dense-caloric muck meant I deserved to be happier—I was putting in effort and thought for my own happiness, I was earning my right to be happy, beautiful, thin. Why, then, did I feel so indifferent? The lack of emotional congruence disturbed me even as I congratulated myself on my self-restraint.

My insecurities over body image also stemmed from peer pressure and the opposite gender’s gaze. In typical Mean Girl fashion, I wanted to be seen and accepted for who I was, but I also felt compelled to put up a front, to fit into stereotypes of what was accepted and desirable.

Due to the academically rigorous and high-performing environment I was accustomed to, I equated skinny to discipline and deemed skinny as a totem of self-care and dignity. If you were thin, it meant you were health-conscious. You ate the right things, you exercised. You were diligent, and you put in the effort to take care of your own body.

It did not help that dance was an art form I had pursued all my life. As a dancer, you observed yourself in the mirror during practice. You compared. Dance instructors are ruthless at being simultaneous physique builders and self-esteem shredders.

All these implicit expectations and offhand judgements coalesced to form a skin adhering to my own, one I sought so desperately to crawl out from but ended up inhabiting instead.

Piecing together a broken mirror

Things only began to demystify in the latter part of my teenage years, when I consciously reflected on these issues and realised something was amiss. I noticed when my friends skipped meals for recess or when someone asked for less rice at the economical rice stall. I paid attention to the media I was consuming, identifying instances of unconstructive body critique or unattainable beauty standards.

It took growing up, true growing up, to untangle myself from the tyranny of body image and re-examine my relationship with food. It is one thing to be skinny in size and shape and another to have a healthy BMI in keeping with your body’s energy requirements. There are healthy ways of eating and unhealthy ways of eating. Sometimes, the way we eat may not translate directly to outcomes.

Granted, I am not immune to the cult of “the ideal body” as advertised by the mass media. I still try out diets and entertain the idea of intermittent fasting. I exercise to feel a little less heavy at the end of the day. I am, however, trying very hard to eat and live for myself, instead of anybody else. A shift in mindset takes time but is not impossible.

Can I protect my daughter from the same?

As a society, we are changing the ways we discuss body image. With the advent of self-actualisation and social media upending cultural norms and establishments, we are having broader and more fulfilling conversations about what we want health and beauty to be.

A few years ago, the no-makeup movement gained traction with Alicia Keys declaring she would go makeup-free indefinitely. Other celebrities followed suit, posting #nomakeup selfies of themselves on Instagram and encouraging followers to do the same. Organic and natural were heralded as the new beauty. Makeup was declared as no longer “necessary”. The point was to be authentically and unabashedly yourself while being environmental and cruelty-free. Women were empowered to feel comfortable and at ease in their own skin.

Increasingly, we are embracing and even celebrating bodies of all shapes and sizes. Individuals are lauded for their inherent worth as people, with a focus on one’s strengths, values, and dispositions. While appearance may affect how one is seen, it is not paramount and certainly not the be-all and end-all. This occurs alongside the call to be beautiful “inside out”, putting the whole person into perspective. Serena Williams and Gigi Hadid shared pictures of their evolving bodies during their pregnancy, relishing the joy of nubile motherhood. Plus-size models started to feature on runways, with the fashion industry finally acknowledging big can also be beautiful. Barbie, the iconic doll almost every girl starts playing make-believe with, now comes in four different sizes: original, petite, tall, and curvy.

Health and fitness influencers are also pivoting from “eating clean and healthy” to “eating for nourishment” and “eating for hunger”. With individuals joining the movement and role-modelling for each other, we have hope we are carving out a better path forward.

I sat with the anorexic patient, listening intently as she shared her story.

“It was a priority in life,” she stated. My eating disorder was my toxic best friend. I could always turn back to it for comfort and security. It was the validation I craved for.”

“And where do you think you are now? Or, where would you like yourself to be?” I prodded gently.

“I think I would like to get better,” she smiled wistfully. “I would like to get my kopi with sugar and milk. Taste the sweetness and savour it.”