All images by Yee Jia Ying for RICE Media.

It’s 7 AM on a Friday morning when Linus Lin emerges from his HDB void deck in Bukit Panjang. It’s the day of his O-Level Biology paper.

He’s 44, married, with no kids. And this is the eleventh time he’s taking the annual national examinations for secondary school students.

Linus, the co-founder of tuition centre Keynote Learning, is literally practising what he teaches—he’s been prepping his students for the exams and he’s sitting for it alongside them. This year, he’s slightly nervous about Biology, because it’s been getting trickier every year, he admits.

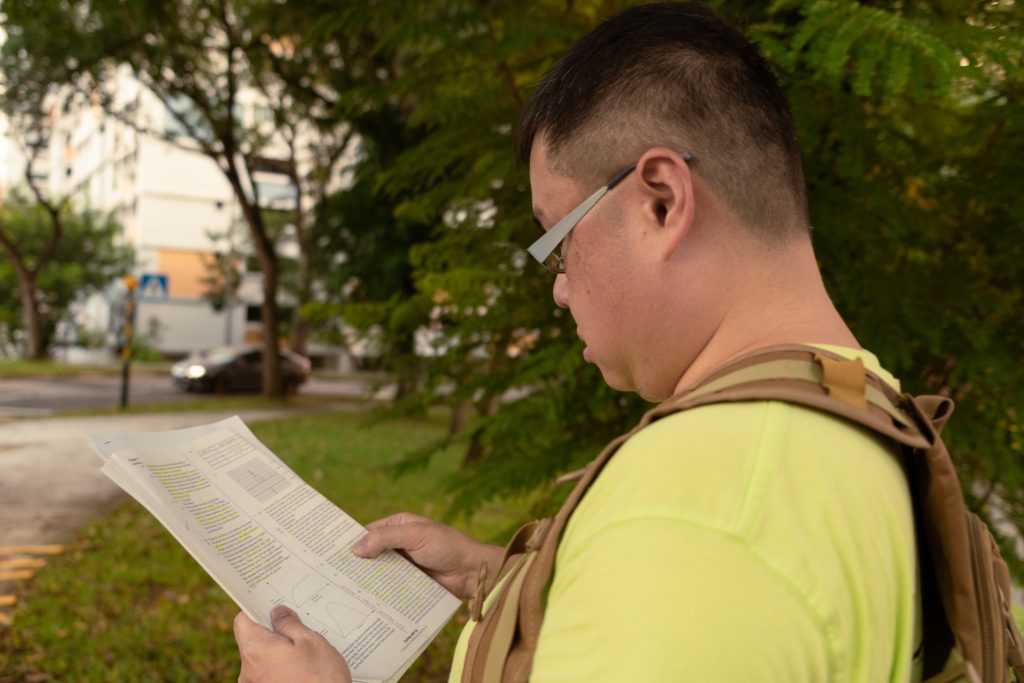

Sporting a neon yellow Mount Kilimanjaro shirt and a practical, army-green backpack, Linus looks ready for all terrains, including (but not limited to) the exam hall.

Besides Biology, Chemistry, and Physics, which are the main subjects he teaches, the man has also willingly thrown himself into the deep end, signing up for additional subjects such as History, Social Studies, and Business Studies. Just to get the “full exam experience”, he says—he wants to take subjects he hasn’t done before and understand what it feels like to be overloaded with revision.

Perhaps it’s an occupational quirk, but every anecdote from Linus comes accompanied by a lesson.

When I ask about his annual pilgrimage to the exam halls, his takeaway is this: “I realised that if I step out of my comfort zone, it keeps getting bigger and bigger.”

“I personally value sharing personal stories to inspire my students,” Linus adds earnestly. “Taking the O-Level exams every year is part of that story.”

Admittedly, it’s not unheard of for local tutors to take the national exams. Some do it for credibility, others for bragging rights.

But Linus’s motivation feels different. It’s almost like he sees O-level exams as an annual personal development ritual.

An Easy Routine

So much of Singaporean life hangs on how we perform in national exams—where we study, the careers we end up in, and even how people size us up.

Just as the PSLE marks the end of primary school, the O-levels mark the next big crossing. For many of us, they’re also stressful experiences that we never want to relive.

For Linus and his colleagues at Keynote Learning, the decision to retake the O-Levels began pragmatically. After a change to the Physics and Chemistry syllabi in 2014 led to grouses from students, they decided they needed firsthand insight into what their students were facing.

2015 would be the first year that Linus sat for the O-level exams as an adult. But Linus tells me that it quickly became a personal challenge and a way to bond with his students.

“First of all, I will shock the student when I tell them [that I am taking the O-level exams], so that brings about a conversation. And then I’ll tell them funny stories I see during the exam and so on. Eventually, there’s this feeling of ‘I am with you on the same boat.’”

Indeed, he looks the part of the nervous exam-goer as he chomps on a bun at his void deck, fuelling up before his paper at 8 AM. We’re meeting here because his examination centre is a secondary school that’s a 10-minute walk away.

Despite being an old hand at the O-levels, Linus still takes it very seriously each time. He insists on eating at least an hour before any exam and drinking plenty of fluids 30 minutes beforehand.

“You don’t want to waste your exam time in the toilet,” he says. Which explains the second half of his ritual: making sure he has fully emptied his bowels before the paper, so nothing distracts him. Of course, we don’t stick around for that part.

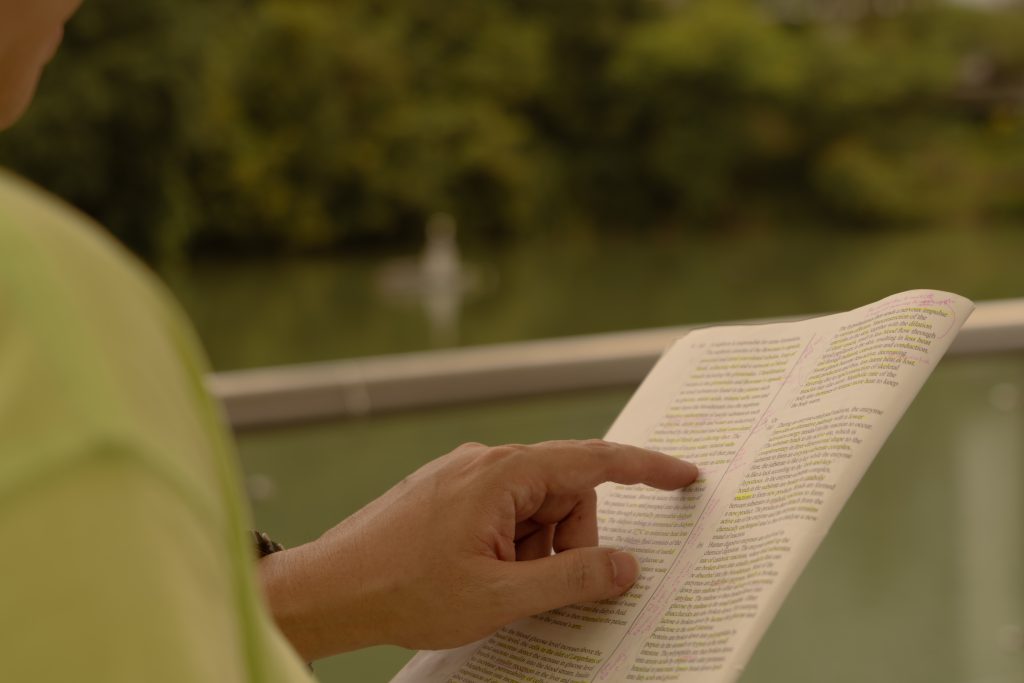

He digs out a set of notes as we start walking together to his examination centre, his bespectacled eyes scanning keywords like enzyme, substrate, and homeostasis while his fingers trace the lines.

He’s sitting for Biology Paper 2 today (the one with the open-ended questions). I follow silently, reluctant to disrupt his last-minute revision. As a former last-minute crammer myself, I know how precious those last hours before an exam can be.

Originally, he’d planned to squeeze in just one more round of revision last night, but he got sidetracked by his students’ frantic messages about other subjects. By the time he was done, it was already 11 PM. He had to retire to bed—getting a good night’s sleep is another one of his exam prep tips—and save the revision for this morning.

We’ve reached the school gates. Still gripping tightly onto his notes, Linus looks up momentarily to bid me farewell. The next time I see him, he’ll be done with his Biology Paper 2.

Linus looks slightly stressed, but there’s also a glint of excitement in his eyes.

The Making of an Educator

I suppose I’m a little curious as to what Linus really gets out of going through the O-Levels every year. And why, of all things, did the O-Level exams become something of a hobby and annual personal challenge of his. When most Singaporeans want to challenge themselves, they usually run a marathon or sign up for Hyrox.

When we meet up after his paper, he offers a little more of his backstory.

Linus didn’t set out to be an educator, nor did he dream of becoming an entrepreneur. He grew up in a family that prized stability, so naturally, he had one of the most mainstream Singaporean childhood dreams: becoming a doctor.

His father, who used to work as an electrician and a train technician, has a mantra: “The hero dies first”. This colloquialism essentially warns one against rushing to the frontlines—and Linus did shy away from battles altogether.

Whatever Linus did, this saying echoed in his head. He avoided making presentations, deflected leadership roles, and stuck to the safest options available. And when he became the first in his family to attend university, he chose computer science because it seemed like a sensible choice.

Halfway through university, he realised it wasn’t his path. But finishing the degree felt like an obligation.

“I didn’t want to disappoint my parents, so I completed the degree. But I also went through this process of, you know, who do I want to become? I then realised I definitely want to be an educator for life.”

In 2001, his first year of university, he started teaching private tuition and found purpose in education. Instead of chasing success and climbing the corporate ladder, he found it far more meaningful to inspire his young charges to pursue their own successes.

When he graduated from university in 2004, he knew he didn’t want to take a conventional job. But he also felt shackled by the “hero dies first” mentality he’d grown up with.

At that point, he says, he decided he needed a drastic lifestyle change to break out of the mindset. Essentially, he wanted to launch himself far outside his comfort zone.

“I told my parents that you should not give me a single cent. From now on, I want to think of a way to figure it out by myself… So I keep throwing myself challenges. There was one time I totally didn’t go home for one whole month and see whether I could actually survive on the streets.”

He tried being a life coach. His bank account dwindled. He spent nights approaching hawkers for discarded food. Strangely enough, Linus says he learnt confidence and resilience.

Linus tells me, without a trace of irony, that he calls his three years of self-development ‘Linus’s University of Life’.

At first, his father was incensed at Linus’s refusal to get a stable job. But he slowly began to accept his son’s unconventional self-help methods.

When Linus finally started his first tuition centre in 2007—a small space in Beauty World Centre—his father became his first investor and even volunteered to fix up the centre’s lighting. Years later, in 2016, he co-founded Keynote Learning.

“Our objective is very clear. We want to build academic success for our students, but we infuse a life skill component into our classes.”

He tells me about a hiking trip to Indonesia’s Mount Ijen, where he saw locals pushing tourists up the mountain in wheelbarrows.

“I brought that story back to my students, and we talked about the science aspect—the physics of pushing the wheelbarrow up. But then we also talked about the ethics. Is it right for people to do this?”

Still, Linus is pragmatic. Parents would rather pay for academic results than for personal development when they send their kids to tuition. What he’s doing now is a compromise—raising his students’ grades while imparting life lessons at every available opportunity.

He sees his annual O-level routine as just another way to do that. He believes education is life-long, not checkpoint-bound; that adults forget what it feels like to learn under pressure; and that students absorb stories more deeply than advice.

One story Linus tells them is about how hard it is to study as a working adult. As a child, he remembers watching his technician father studying late into the night for an Institute of Technical Education certificate.

Now, an adult himself, he reflects: “Your own studying is always the last priority. Therefore, I developed a deep sense of respect for people who are studying part-time while still pursuing a job and have a kid.”

“Don’t take your parents for granted,” he tells his students now. “You don’t know what they go through for you.”

Insights of an Exam Expert

Linus has taken the A-Levels too—General Paper, Physics, Chemistry—on the premise that to teach well, he must excel at the tier above what he teaches.

His dedication to taking these exams year after year also means he’s found himself in a pretty unique position; he’s one of the few people with a firsthand look at how our national exams have changed.

“The complexity of the papers has increased,” he says. “We used to be able to score A1 in pure science subjects just by depending on the Ten Year Series, but it’s not possible now.”

“Adults forget that exam results aren’t a straight function of effort. More tuition, more practice papers, more grind—it doesn’t automatically mean higher marks anymore.”

What worked when he was a student, he adds, may no longer work for the kids sitting in classrooms today.

His own relationship with exams began in 1996, when he first took the O-Levels. Back then, he scored mostly As, save for English (C6) and Chinese (B4). Still, these were results that far exceeded his family’s expectations.

His mother has a Primary 6 education, while his father only passed three O-Level subjects. The pressure to excel, he says, came not from them but from within: “I wanted to bring them pride. To be a role model for my younger brothers. The stress was self-imposed.”

He still believes national exams are vital, both as a way to build intellectual ability and as a pillar of Singapore’s meritocratic system. But his years as a tuition teacher and exam taker have shifted his views on what exam scores actually mean.

“I used to think people needed to do well to deserve a better life,” he admits. “Now I see national exams not as judging tools, but diagnostic ones. If you don’t do well, it simply means you might be more suited for another field.”

The Climb

Outside the classroom, he’s climbed Kilimanjaro and Mount Fuji, and trekked to Everest Base Camp, chasing both the physical challenge and the introspective solitude of long-distance walking.

All of it feeds into a worldview he tries to pass on to as many young minds as possible: Self-improvement is a habit, not a destination. Courage accumulates one uncomfortable experience at a time. Academic success is only one part of life.

That being said, he’s aiming for all A1s again this year. Biology worries him a little; English might slip to an A2 thanks to a “very tough” listening comprehension paper. Physics and Chemistry are, as always, a walk in the park for him.

But the grades are almost incidental. For Linus, the O-Levels have become something like an annual self-development report card. Of course, the results matter—he is, after all, a tutor whose credibility is scrutinised by paying parents—but they’re not why he does this.

“Is there some part of you that actually enjoys the process?” I ask.

He pauses.

“There’s a breakthrough feeling that comes with it,” he says. “And it is… very addictive.”

In an education system built on fear of failure, it’s fascinating that Linus has turned a national exam into something else entirely: a mountain he climbs each year.