You are freckle-faced fifteen, February fumbling in your fingers. You still can’t get a grip on how things have changed.

The girls stand straighter, their eyes more wary. The boys are louder, rowdier, moodier. Six weeks of holiday went past, and suddenly there’s a new normal. As though a switch flicked and everyone’s seeing clearer now.

Your fingers crumple into your palm. You’re not sure how you’re going to get through the year.

⚀

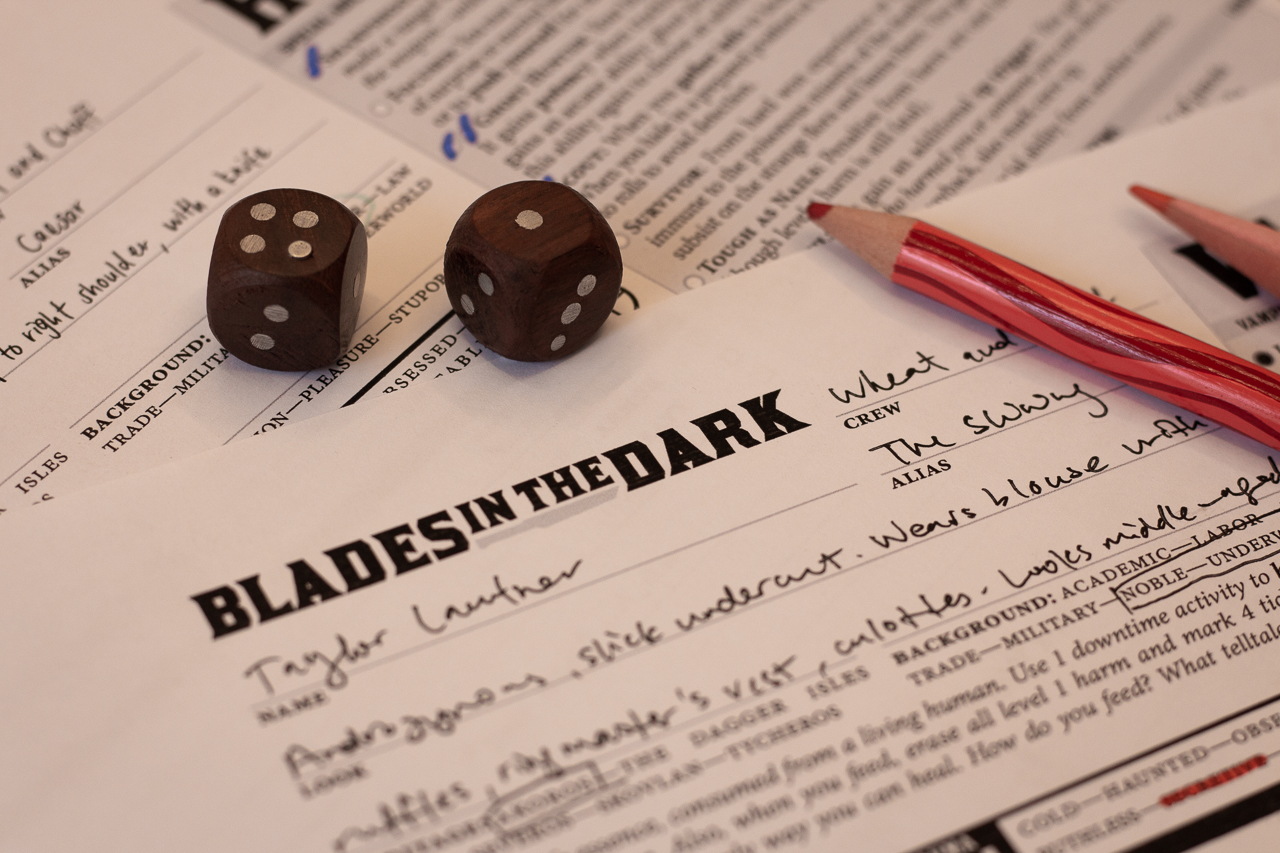

Tabletop Roleplaying Games (TTRPGs) are one of those obtuse, niche hobbies that people associate with nerds or children. But stripped to its essence, it is procedural, collaborative, verbal storytelling.

Whether by embodying their own characters, or as the game master (GM)—moulding the in-game universe and other non-player characters—players take turns narrating a story together. It’s the adult version of children pretending to be superheroes at a playground, or playing house—it’s make-believe taken seriously.

But things don’t go exactly how the players want. It’s a game after all, and an element of randomisation is introduced through mechanics like rolling dice.

Because of this, failure is rampant in TTRPGs—much more common than clean successes. But you just have to keep moving, not just in spite of failures, but because of them. There is no ‘game over’ and repeat loop. Each consequence sticks, and you have to make the best out of the cards you’re dealt.

In tabletop, as in life, this is known as failing forward.

“Left!”

You’re stumbling on the court, the last pick of the basketball draft.

Somehow, the ball makes its way into your hands. Somehow, you haven’t dropped it. And somehow, you’ve been marked by a 1.8m tall girl with her hair brought back in a tight ponytail.

“Shoot!”

The tall girl sniggers, her armpits blocking your view of the hoop.

You wind your hands backwards in your desperate attempt at a final stand. Before you can fling the ball, it’s knocked out of your hands.

Shouts swerve around you as the game continues. You hang your head.

⚁

The game progresses by succeeding or failing at reaching your intended outcome through your actions. By attacking the thief you hope to slow them down. By seducing the consular you want access to their bedroom.

Characters normally have certain stats: strength, intelligence, dexterity etc. You should ideally play to what your character’s good at to succeed. But if your GM’s a bit of a dick—and the best ones are, because conflict is interesting—you’ll be put in situations you suck at. You’re bound to roll with the odds stacked against you.

However, failure exists in shades. There’s a neat improvisation exercise to add colour to your obstacles: tacking on a ‘but’ to your successes and failures. So you could succeed in slowing the thief during your attack, but in doing so make a sound that draws allies to reinforce them. You could fail at seducing the consular, but cause their paramour to be jealous, allowing for another opening.

This allows complications to arise while still granting an opportunity to move forward. It’s up to you to find creative ways to make the best use of these.

⚂

You switch gears. If you can’t score, you can surely be a nuisance defending. Your mark is a wiry, jumpy boy who ricochets across the court. It takes every iota of effort to stick to him.

It doesn’t matter that you slap the ball out of the court, or let him outmanoeuvre you half the time. You put pressure on his movements, and it shows.

Your team still loses, but barely.

Afterwards, he gives you a fist bump, a gesture of solidarity between sportsmen.

“You’re annoying,” he chuckles. “I like it.”

You don’t step on court again, but you act as commentator for your peers’ matches. Your woeful lack of basketball knowledge makes your commentary even funnier, and the players sometimes execute unconventional, guerrilla strategies just to be noticed by you.

Without a lick of passion for sports, you still manage to bond with your basketball-obsessed classmates.

The girl with wavy shoulder-length hair and dark stick-on fingernails is sitting behind you for History remedial. You feel sweat on your collarbone.

Five minutes till class begins. You rock your chair back ever so slightly, mulling over how to approach her. Then she snorts—a gun shot of laughter followed by shotgun spittle on your neck.

Startled, you fall backwards, but her table catches your chair.

“Sorry!”

“It’s alright,” you reply. Your mind’s a blank, but you mouth continues moving.

“History, huh? Waste time only.”

“I find it okay eh,” she shrugs. “I quite like the subject, I’m just rubbish at SBQ.”

“Oh yeah, it’s okay lah,” you nod.

There’s silence as the both of you stare at each other, processing your idiotic, contradictory statement. She raises an eyebrow.

“I mean-”

But she’s no longer listening, looking at her phone. She thumbs her feed, moving from one hilarious meme to the next.

You slink back, defeated.

In the weeks that follow, you never recover. Sometimes, she grins at you in the corridor, but nothing more.

⚃

Sometimes, consequences suck.

When you’re playing in the fictional world, your actions stick, and your failures especially so. You let the dragon escape, and it razes a country. You accidentally kill your informant, and the real killer goes scot free.

It happens. You might have to make tough choices in the heat of the moment, have tunnel vision or overestimate yourself, or just end up plain unlucky.

You could wallow in your misery, but the world keeps moving. The game reminds you that there are things to be done, that as protagonists you cannot dawdle.

But you aren’t allowed to ignore your mistakes. They will come back to haunt you—trading routes disrupted because the country is now scorched earth; the victim’s mother is still seeking closure, driven to self destruction. The only way to move forward is to take ownership of your actions, learn and grow from your mistakes, and accept that some losses are irreversible.

You might lose a limb or never be allowed into your home city again. But you gotta roll with the punches.

You don’t have to stay in-character all the time.

When the stakes are high and uncertainty is peaking, or in the wake of a catastrophic mistake, players often take a step back and discuss how to move forward with the group.

Being able to dissociate from your character allows you to reflect on the big picture. To calm down, and think about your character’s wants, needs, and how they fit into the story you want to tell. This exercise has often given me clarity on what needs to be done next.

And if you’re stuck, you can ask for help around the table.

What else can I do differently? Is there something I haven’t considered? What are the potential consequences?

When you’re brainstorming alone, it’s easy to spiral into anxiety, trapped by your thoughts. But when you do it with others, it’s problem solving bundled into a heart-to-heart.

⚄

Dusk blooms, and your head’s between your knees as your best friend sits next to you. They’ve always told it straight to you whenever you’ve fucked up. Like now.

“You shouldn’t have brought up Eric’s family,” they tell you.

“What could I have done?” you sigh. “I wanted to help-”

“You just made him more defensive. Maybe if you were closer, and maybe if it was in private. But in front of the rest like that-”

“We’re not close meh? Aren’t we all-”

They put their hand on your back, and shake their head.

“You know Eric doesn’t open up easily,” they say. “And now he’s going to be more withdrawn and paranoid over how you found out.”

“But Victor told me, and he’s Eric’s best bro, so I thought everyone already-”

“Don’t assume lah! I’m sure Victor only told you because you’re in a similar situation. Next time, please be more sensitive.”

You run your fingers through your hair, nails hooked into your scalp.

“I should apologise.”

“Yes, but give him some space,” your friend tells you. “Send him a message.”

“Handwritten?”

They smile. “I’ll make sure he gets it.”

The next few years are a blur. You struggle in your studies, and you end up having to retain in your program when you’re seventeen. You decide to drop out instead.

You make the unenviable decision of pursuing a private diploma. It’s 2.5 years of enervating work, spliced with co-curricular and familial commitments. But you make it through, graduating near the top of your class.

When you apply for local university, you don’t expect to get in. But you do. It took a lot of blundering, and an academic path you never imagined you’d take.

But you’re still here.

⚅

“You have to play to find out what happens.”

This is one guiding principle held by Austin Walker—GM and host of TTRPG podcast Friends at the Table, and Editor in Chief of VICE Games. It’s a nod to the fact that you can never truly predict anything absolute in a tabletop campaign.

Even the most well constructed and guaranteed plans can become rubble and ash, and the most unlikely gambits can pay off.

The only way to discover the answers to your questions, to collapse a nigh infinite simulacra of possibilities into a single reality, is to commit, be a player, and put yourself on the line.

You just have to roll, and hold your breath.

We’d love to form a table with you (please hit the author up). Roll with us at community@ricemedia.co.