Raymond Ng is a businessman.

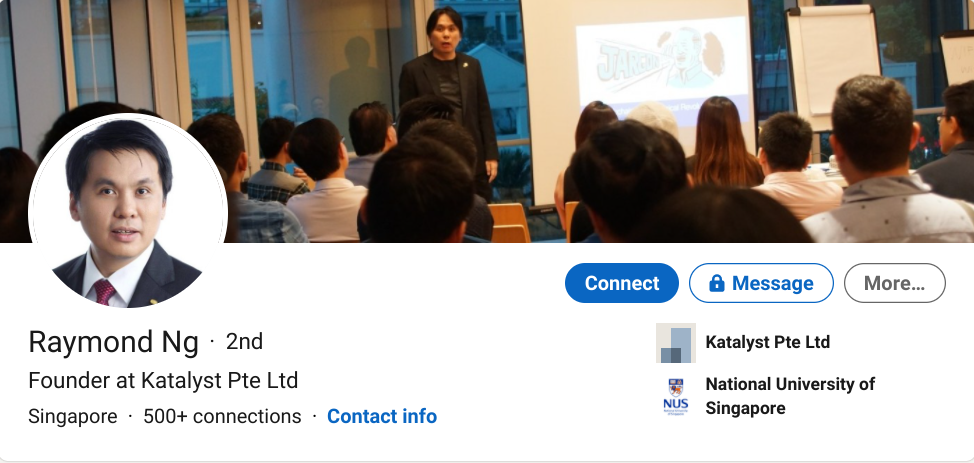

On LinkedIn, Raymond presents himself as an entrepreneur, graduating from NUS with a degree in Computer Science. His companies are registered in Singapore under various names, including Katalyst Pte. Ltd and Candle Consulting Pte. Ltd.

One of Raymond’s business ventures is Vendshare, a company that enables ‘franchisees’ to co-own stakes in coffee vending machines located across Singapore. On Vendshare’s website, the company states that it wants to “empower the middle class to grow their income,” by using ‘blockchain technology’ to distribute profits.

Interviews conducted by RICE, however, paint a different picture of Vendshare’s activities:

1. Raymond has collected deposits from over 200 Singaporeans under the Vendshare scheme. These franchisees hail from all walks of life: students, retirees, self-employed Grab drivers, civil servants, and people with disabilities.

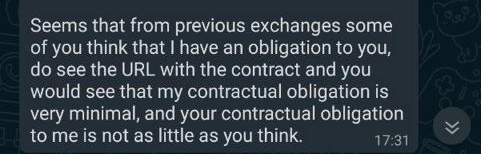

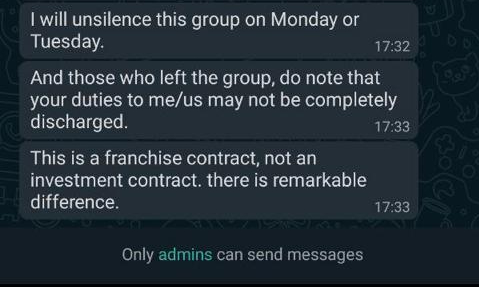

2. Through in-person interviews conducted by RICE, as well as Whatsapp conversations, dozens of franchisees have alleged that Raymond collected deposits from them upfront and provided no payouts in return. Raymond’s reason for non-payment? Their contracts do not stipulate that franchisees must be paid.

3. Raymond has had at least seven police reports filed against him by Vendshare franchisees.

Complaints about Raymond’s company Candle Consulting Pte Ltd have also been published on a website called Scamsg.com, where one reviewer alleges that Vendshare is ‘a complete scam’.

Despite these allegations, Raymond has not been charged with any wrongdoing.

According to franchisees who went to the police, SPF declined to investigate further, explaining that there was currently “not enough evidence”, and “not enough police reports” being filed.

This begs the question: why aren’t more franchisees going to the authorities or taking steps to protect their legal interests?

Finally, in ‘law and order’ Singapore, how many police reports need to be filed against one individual / business for SPF to take action?

Who Are These Franchisees?

-* all franchisees RICE interviewed requested anonymity

“I first heard about Vendshare in August 2019,” said Winston, who is a university student in his early 20s. “I saw Raymond’s advertisement on Facebook, signed up for his newsletter, and joined a free webinar. Then I went to the live session to hear Raymond give a presentation at his office. In total, I paid $3,000, which is the price for one lot.”

“Vendshare was recommended to me by a trusted friend,” said Eric, 58, a retiree. “I went straight to Raymond’s office for a talk. After the talk, I paid for five lots, worth $15,000. Raymond gave me a discount for paying a lump sum. So in total, I put in $13,800. My friend had bought ten lots himself, for just under $30,000.”

“Someone shared a Zoom link to Vendshare webinar on a Whatsapp jobs group I joined when I was unemployed back in early 2019,” said Peter, 32, who is confined to a wheelchair. “After that, I paid Raymond $1,500, which is one month of my take-home pay, before other franchisees warned me to stop.”

What was their first impression of Raymond?

“He sounded quite convincing,” said Peter. “He told me that I could earn a bit of passive income in the vending machine business. On my small salary, that was important to me. I used all of my savings to invest in Vendshare. Even then, I had to pay by installments.”

“To be honest, my first impression was that he was a bit arrogant,” said Winston. “He started his presentation with ‘first of all, I’m not here to waste your time…’ He had this air of: ‘I can help you make money. If you’re not interested, I don’t care!’ type of attitude. There was no hard sell. The returns he was promising — $200 per month per lot — sounded quite reasonable. It didn’t feel like a ‘get-rich-quick’ scheme.”

“He was very secretive though,” said Eric. “In hindsight, there were questions I asked him that he did not answer. I assumed it was a business secret. At the time, I felt OK because of his credentials. He had a degree in computer science from NUS, authored a book on blockchain and claimed he’d worked with 3,000 consulting clients.”

Despite these early warning signs, why did they go ahead to put money into these schemes? Eric, the retiree, summed up the group’s sentiments best:

“We weren’t looking to get rich quick. We simply wanted to make some passive income to tide us through tough circumstances. Just look at how local banks are lowering their interest rates 3-4 times a year, while cost of living is going way up. We have to find ways to invest!”

How the Vendshare Scheme Works

At Vendshare, bidding starts for a vending machine location before the machine is even procured.

‘Franchisees’, who were solicited through webinars or attended the live presentation would be invited to a Whatsapp group chat, where Raymond or one of his staff would open the bid on a location, requesting deposits upfront.

For example, a Tiong Bahru location may have five lots. Each lot is worth $3,000, and represents an ownership stake in the Tiong Bahru coffee vending machine, entitled to one-fifth of the machine’s profits.

To secure this lot, franchisees compete against each other to place their bids via Whatsapp. Putting $500 down gives you priority to choose your lot and location. Putting $1,000 gives you higher priority. Of course, franchisees can opt to pay the full $3,000 upfront and secure the lot and location of their choice.

‘Winning’ franchisees are then sent digital contracts and an NDA (non-disclosure agreement) to review, which they are not obligated to print out or sign.

At this point, things start to fall apart.

Every franchisee that RICE spoke with recounted that Raymond’s updates on the machines would become increasingly scarce — until they stopped entirely. Some vending machines were never installed at their promised locations.

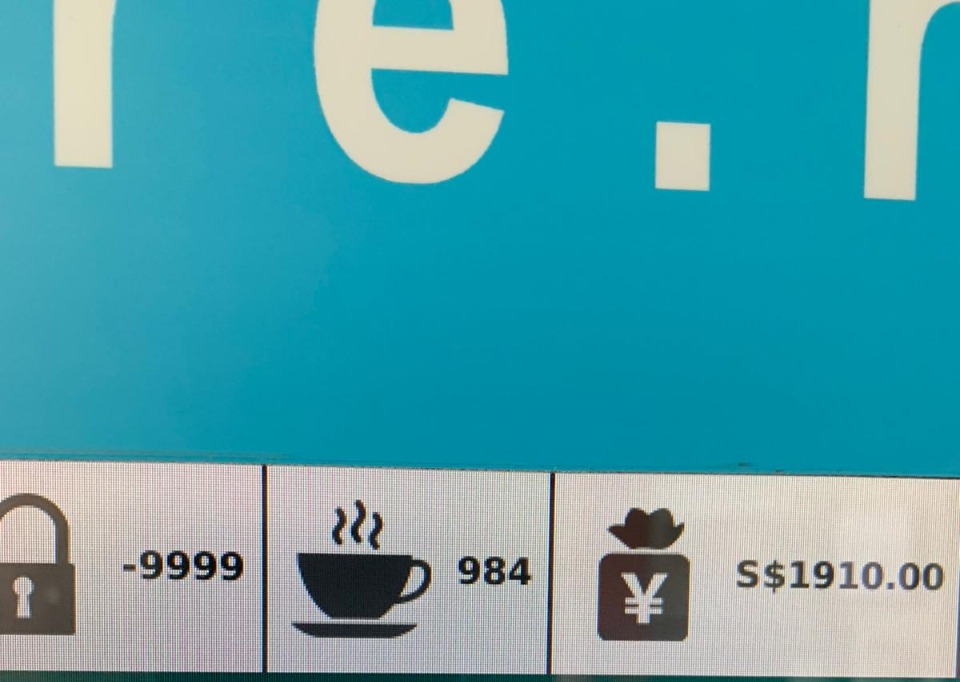

For the franchisees whose machines did get installed, Vendshare’s promised payouts never materialised, despite evidence that the machines were earning revenues.

When franchisees started demanding answers, Raymond threatened to bring lawsuits for defamation and breach of contract, and severed communication by kicking them out of the franchisee Whatsapp group chat.

“None of us know exactly how many vending machines are physically in Singapore,” said Winston. “Most recently, Raymond claims he has about 25 machines placed across Singapore. But according to the evidence we have so far, he has collected deposits for at least 43 machines already.”

Why Many Franchisees Do Not Take Legal Action or Go to the Police

“Yes, I did make a police report at the station as soon as I learned I’d been scammed,” said Peter.

“The Investigating Officer (IO) told me that they’d already received several reports on Raymond, but he explained that because there were too few reports, the police could not move forward with the investigation.”

Before he left the station, the IO told Peter not to respond to these investment schemes in the future.

“But he’s already taken my money!” exclaimed Peter.

Despite the fact that there are numerous allegations against Raymond which appear to provide reasonable grounds for investigating or inquiring into Vendshare’s operations, it is unclear whether investigations are ongoing, or what actions are being taken to look into Raymond’s conduct.

The next logical step was to consult legal counsel, but the franchisees I spoke to were surprised when their lawyers advised against pursuing a claim.

The reason was simple: the legal cost for an individual to take Raymond to court would far outweigh the money they’d stand to get back. Depending on the outcome of the case, this could risk hurting their wallets even more.

But the main reason why many franchisees do not take legal action or file police reports at all is because of shame. They either borrowed money from relatives and loved ones, or do not want to be judged as gullible and stupid. Some work in the civil service; at least one franchisee is a police officer himself.

Many are between jobs, and worry that being involved in an ongoing legal dispute might hurt their chances of getting hired. Most job applications require them to check a box to disclose whether they are involved in any ongoing police investigations or, according to one franchisee, in legal disputes.

“Some are spooked by the contract and Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) Raymond made them sign,” said Eric. “But if he’s doing something wrong in the eyes of the law, he cannot enforce these agreements!”

“This is a Matter of Principle”

The group of franchisees who were willing to speak to RICE in person is only a small fraction of Vendshare’s investors.

Why are they willing to speak up against Raymond?

“For us, the money that we lost is not life-or-death,” explained Winston. “I only lost $3,000. Not small change by any means, but as a student in my 20s, it will not damage my financial prospects permanently. This is a matter of principle for us.”

Winston claimed that “Raymond threatened me” when he asked for an explanation. According to Winston, Raymond said on a call, ‘You’re in your 20s, a student. I can drag you into a lawsuit for seven years and ruin your employability and life!’ I made a voice recording of this call, where he was verbally abusive and aggressive towards me.”

“If nobody stands up to this guy, then he will keep getting away with it,” said Eric. “He will keep collecting money from vulnerable people, and nothing will happen to him. Vendshare is not an isolated venture. As we investigated Raymond’s activities, we just kept digging up more dirt. It’s really disgusting. The fact that this person can continue to do this to people and get away scot free.”

“It doesn’t sit well with us.”

What they would like to say to Raymond if he were sitting across the table from them?

“You reap what you sow,” said Winston.

But these franchisees weren’t sitting around and waiting for karma to materialise. For the better part of last year, the group has been diligently documenting evidence, voice recordings, and speaking to other franchisees to collect their testimonies.

Despite these efforts, they are worried that they will have no other recourse and cannot recover their investments.

Catch Me If You Can

“If you just give me thirty seconds…”

By now, these Youtube ads have become so familiar to Singaporeans that they border on parody. In this recession, alternative business schemes and other unregulated financial products soliciting the public through phone calls and text messages have become a weekly occurrence.

Meanwhile, the stock market and real estate markets are at all-time highs.

In effect, Singapore has become a tale of two cities: between those who earn their living with capital and those who earn their living with labour. The former naturally believes that PSAs warning Singaporeans to ‘be more careful’ of shady business practices are sufficient deterrents against financial crimes; the latter lives in a reality where they feel like they’re being left behind, and have no other choice.

It’s in this reality that unethical and shady businessmen thrive.

That’s because many of these bad actors know that in all likelihood, they’ll get away with it. The shame of losing their money keeps many people from going public with their experiences or filing reports with the authorities. The prohibitive cost of legal fees means that they’re more likely to write-off their losses than go to court.

The solution to combating these bad actors is two-fold:

1. More victims need to come forward to file police reports

2. Authorities need to be more responsive to these reports

Singapore is known as a law and order society. A financial hub of SE Asia built on prudent regulation and governance. It is a system that is averse to ‘handouts’; one that believes that setting the right incentives, mainly for businesses and employers, is critical to Singapore’s competitiveness.

At what point does this incentivise the wrong behaviours?

In the absence of adequate protections and enforcement, what if a new generation of Singaporeans conclude that this is the way the game is supposed to be played?

Is Singapore prepared to deal with those consequences?

-* All the quotes from interviewees setting out their impressions of Raymond are their personal views and comments on the matter based on the facts available to them and should not be construed as statements of fact.

Any concerned parties may wish to reach out to a coordinated group of Vendshare franchisees via the following email address: me.too.reach.out@gmail.com.

For all other questions or comments related to this article, write to us at community@ricemedia.co.