‘After the Vote‘ is a RICE Media series where Singaporeans from all walks of life share their hopes for Singapore—the changes they envision, the values they want to uphold, and the future they want to help shape.

After GE2025, we take a step back from the political theatrics to explore the bigger picture: What kind of Singapore are we building beyond this election? Through these conversations, we uncover the aspirations and concerns shaping the nation in the next five years and beyond.

All images by Stephanie Lee and Eudea Tan for RICE Media

When The Projector announced it was shutting its doors, citizens sprang into action with petitions to lawmakers in the hope of keeping the independent cinema alive, and an outpouring of tributes. These weren’t part of any sanctioned campaign, but it was active citizenship, no less.

‘Active citizenship’ and its many variants have become familiar refrains, appearing in policy speeches, school textbooks, and even the fine print of grant applications.

Yet the irony is that while institutions exhort us to be active contributors to society, many Singaporeans feel most alive not in official programmes but in the unscripted acts of everyday life—small gestures of kindness and solidarity that aren’t part of any government playbook.

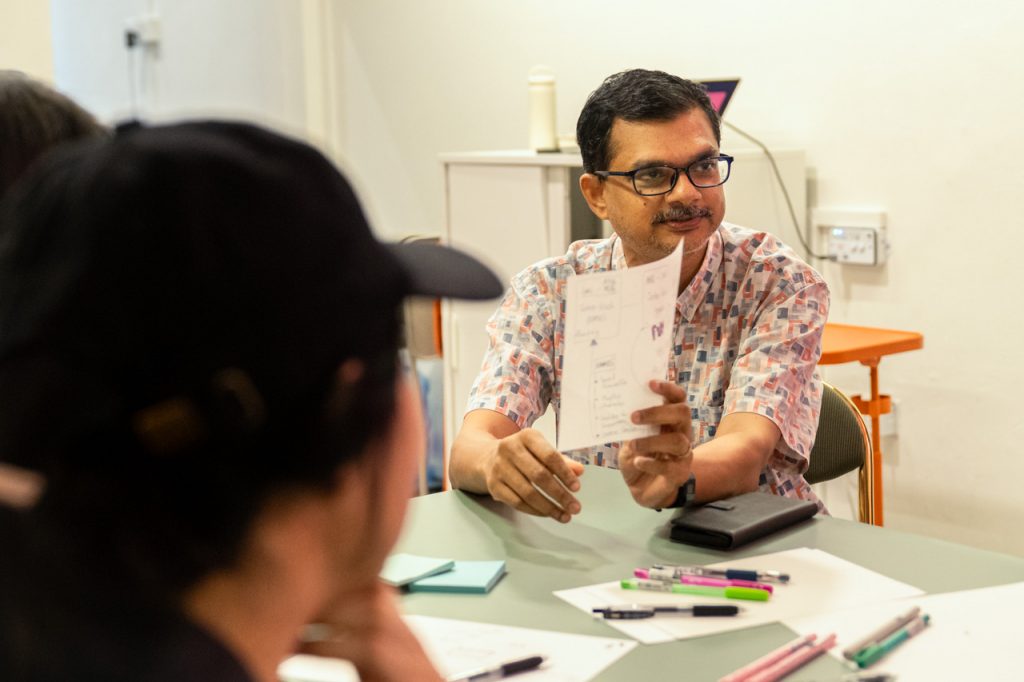

But before participants of a recent RICE Media community dialogue broached that topic, RICE co-founder Julian Wong asked them to consider a more fundamental question: What does nation-building really mean?

Replies shot across the room.

“HDB flats.”

“Economic growth.”

“A sense of belonging.”

Someone even opined “social engineering”, a reminder that much of Singapore’s nation-building has been designed from the top down, not constructed from the ground up.

As participants warmed up to one another, the theme, though straightforward, unravelled into a complex and surprisingly intimate conversation.

What does doing your part mean in a society where most forms of participation are carefully managed, and where passivity has long been the default?

The array of perspectives that emerged offered a glimpse into how Singaporeans imagine community through humour, play, and holding space for others.

At stake is more than semantics. In a nation familiar with didactism, these ideas suggest a different way of belonging.

Dissecting Citizenry

When the discussion shifted to the topic of active citizenship, the room grew livelier and cheekier.

In Singapore, the phrase usually conjures familiar prescriptions: Volunteer your time, donate to charity, join grassroots organisations, and do your part to keep the community humming in step with national goals.

The state has long promoted active citizenship through channels such as Character and Citizenship Education (CCE) in schools or REACH, the government’s official feedback unit.

Some participants echoed this framing, suggesting that citizenship often boils down to working hard, paying taxes, spending money, and redeeming the latest round of Community Development Council (CDC) vouchers.

But several pushed beyond these boundaries, insisting it could also mean exchanging ideas with taxi uncles, helping strangers on the MRT, or the quintessentially Singaporean pastime of complaining.

After all, in a city where dissent is fraught, participants laughed about how complaining is often the safest way to show you still care.

Yet it is precisely the habits that make Singapore orderly—such as deference to authority, fear of rocking the boat, and a preference for letting institutions take the lead—that make it harder for citizens to imagine participation beyond sanctioned channels.

Model United GRCs

Next came a challenge: Julian invited participants to dream up initiatives that could spark the kind of change they wanted to see.

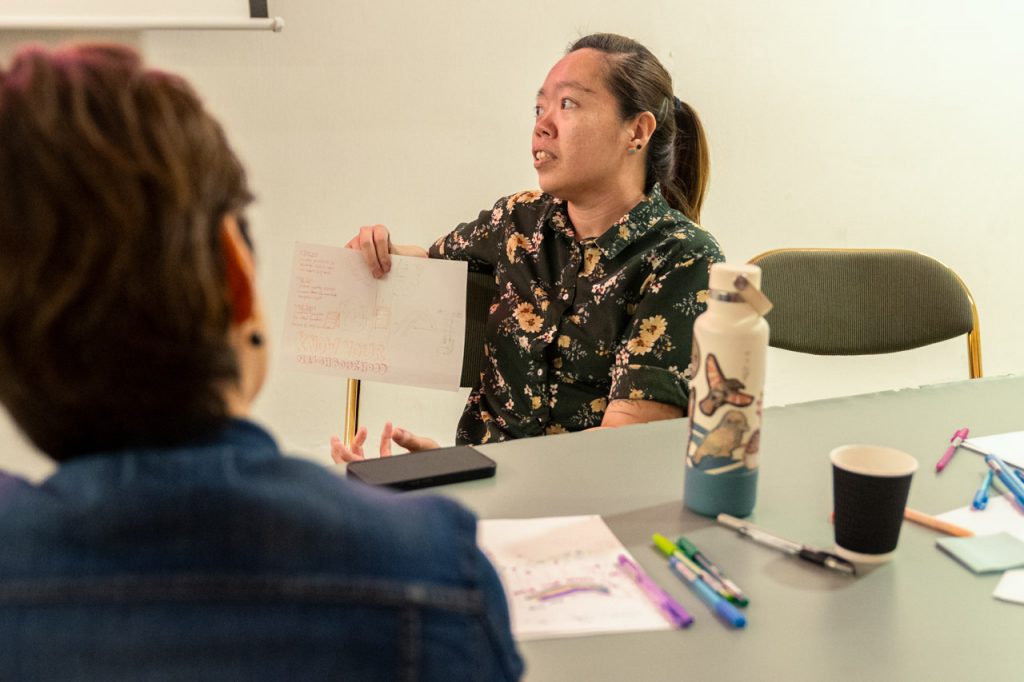

This prototyping workshop, by contrast, revealed how citizens envision civic contributions when freed from official scripts.

One group proposed a “Do Nothing Social Club”, a resistance to the productivity gospel, where resting, enjoying a coffee, and the company of neighbours becomes a civic act.

A common theme soon emerged: Singaporeans’ competitive streak. Members of the audience proposed team missions like mock fire drills, litter-picking relays, or community gardening challenges, all with tongue-in-cheek rewards like primary school balloting perks or even extra years on your HDB lease.

Another attendee suggested Singlish Charades, which reclaims cultural “inferiority” as heritage and identity.

Someone suggested labelling the species of the plants around HDB estates, turning an ordinary void deck garden into a slow-reading library of leaves, coaxing neighbours to slow their pace.

Beneath the whimsy, these ideas sketched an alternative Singapore—one that is participatory, empathetic, reflective, and attuned to the small joys of daily life.

A university student suggested a public Telegram channel where Singaporeans could share their favourite foods and places, inviting the world to see Singapore through everyday joys rather than glossy tourism ads.

Participants also pictured void decks where symbolic neighbourliness becomes real material care: Sticky-note message boards for neighbours to share their daily lives, alongside unused nighttime spaces as community-run shelters to offer respite to the homeless.

Others dreamt of intergenerational play corners, where people of all ages can find healing for their inner children.

Even amid the playfulness, it was evident that participants wanted to resist the soullessness that can ironically pervade a city where people live in tightly stacked HDB flats.

Their spirited responses were undoubtedly inspired by a desire to reclaim culture and shared spaces before they vanish. And that might be the fruit of active citizenship, regardless of definition.

Constructive Citizenship

These playful sketches—colloquial charades, coffee clubs, even constructive complaining—might seem unserious. Yet they point to a truth that official slogans often overlook: People feel most alive in the spaces they make for one another, not in the ones scripted for them.

When Singaporeans rallied to fund the Palestinian Scholarship Initiative and aid victims of last year’s Bukit Merah blaze, their collective energy and drive were impossible to ignore. Isn’t that active citizenry too?

The voices in this discussion suggested that kinship can be reclaimed by recognising the humanity in our peers, especially those left on the margins.

So, if active citizenship is to mean anything in Singapore, it may lie in the courage to create a life together on our own terms.

That courage, after all, doesn’t always look like grand speeches or policy papers; sometimes it’s just an individual scribbling affirmations for neighbours on a sticky note, or someone slowing down long enough to read the name of a bougainvillaea.

Perhaps that is the joke and the lesson at once. That in a country obsessed with doing more—GDP, PSLE scores, birth rates—the most transformative acts of citizenship are gentler, intangible, and born from genuine care for the things that truly matter.

As digital echo chambers pit Singaporeans against each other, and the everyday stress of economic volatility intensifies these divides, social trust cannot be restored by policies alone. Rather, healing requires us to see one another not as strangers, but as partners in shaping the place we call home.