This story was brought to you by Healthcare Scholarships.

All images by Benjamin Tan for RICE Media.

Clinical psychologists treating today’s youth are in a curious position. This is a generation more aware of mental health than any before it, fluent in therapy-speak thanks to TherapyTok and pop psychology.

But awareness hasn’t stopped the cracks from showing. In Singapore, reports of depression, suicide, rampant bullying, and even substance abuse point to a generation grappling with pressures that knowledge alone can’t soothe.

For the psychologists working with these young people, the task isn’t simply treating behaviour—it’s decoding the human behind the label. And what they’ve found is unsettling: those dismissed as ‘troubled’ are often just mirrors of the pressures baked into Singapore’s system.

With that in mind, should we rethink how we treat our youth? And what does it really take to identify and exorcise the new demons plaguing Singapore’s youths today?

The Life of a Clinical Psychologist

The task of uncovering these demons often falls on the shoulders of clinical psychologists, whose practice involves the assessment of mental health conditions and the provision of psychological interventions.

Unlike psychiatrists—medical doctors who diagnose, treat and prescribe medication for mental health conditions—psychologists rely on conversation, assessment, and a variety of therapeutic tools and techniques to help patients cope with ongoing life challenges and to heal emotionally.

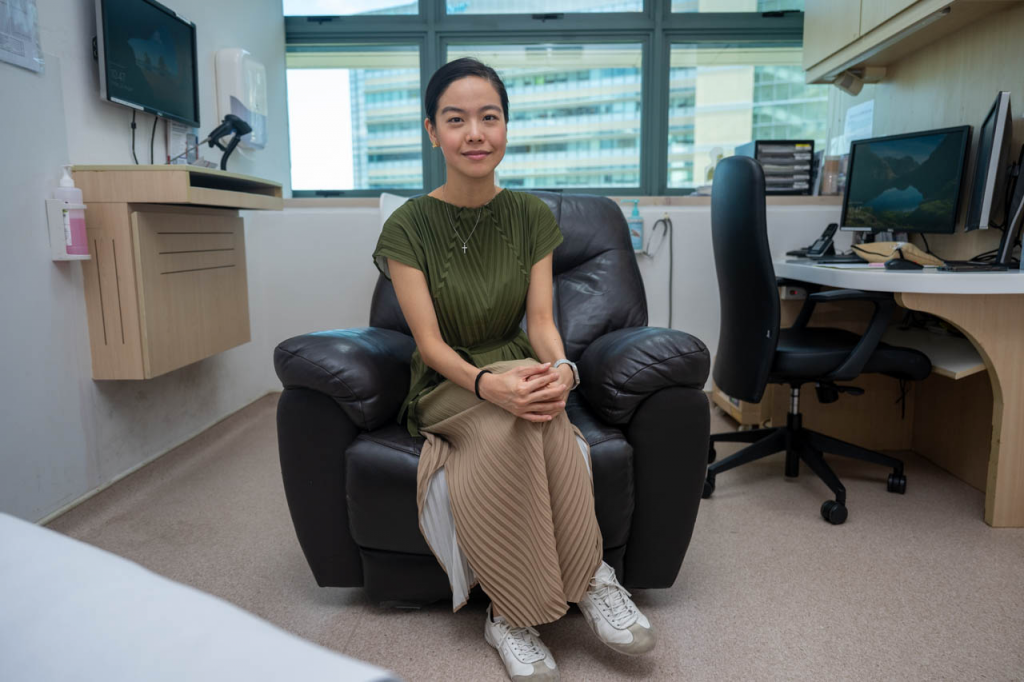

Clinical psychologists in Singapore work with people facing mental health challenges by assessing their mental health needs and developing a comprehensive understanding of their presenting issues. Within the context of healthcare, clinical psychologists attend to patients in a variety of settings, ranging from warded patients to specialist outpatient clinics in hospitals and polyclinics. Some, like Carmen Chew from the Institute of Mental Health (IMH), handle both inpatient and outpatient cases.

Carmen explains that most young people find their way to her through referrals from doctors or school counsellors. But lately, she’s noticed more of them knocking on her door themselves. That, she says, is a good sign of growing awareness of mental health issues among youths.

Still, awareness is only one part of the work. The harder work is teaching parents, teachers, and caregivers how to support their children, which means understanding struggles beyond what’s visible. This means understanding what’s going on with their young charges, getting to the root of their struggles, and being there for them.

To outsiders, the work of a clinical psychologist may look deceptively simple. One enduring misconception, for example, is that therapy is “just talking”.

In reality, it’s an intricate process. Carmen spends most of her days helping people make sense of what’s going on in their lives and the challenges they’re struggling with, and equipping them with tools to deal with those challenges.

But real progress hinges on what’s called ‘doing the work’—actively engaging in self-improvement, healing, and personal growth. Ultimately, taking responsibility for one’s own emotional well-being with the tools learned through therapy.

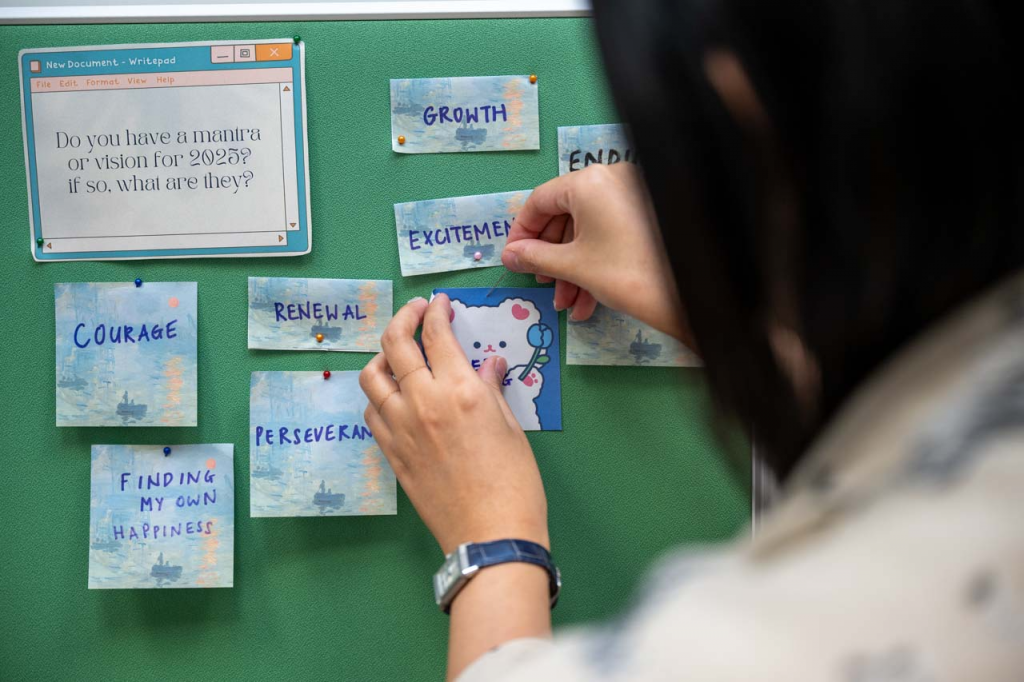

“A lot of the change that happens in therapy actually happens out of the room,” says Isabel Yap, a clinical psychologist at Khoo Teck Puat Hospital.

“At the end of the day, I will always wrap up the session with what they can do in between sessions.”

It can be a slow, painstaking process—in their work, psychologists often need to establish trust with their clients before proceeding. Lee Lexin, who practices at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, upholds the belief in creating a safe space where youths feel heard and validated.

She recalls a client with speech delays. In one of her sessions with him, Lexin had suggested that it might be helpful for him to draw out his life story. In the next session, the boy actually brought her a comic he had drawn about his life. That moment, she recalls, underscored for her the importance of seeing beyond the diagnosis.

“Yes, a diagnosis is important. It guides our interventions,” Lexin says. “But at the same time, you really want to know the person behind the diagnosis.”

Sometimes that even means expanding her vocabulary of Gen Z slang or watching shows that her young clients recommend to better understand their world.

Another common misconception is that therapy is a quick fix.

“Sometimes clients come in and there’s an expectation,” Lexin shares.

“They ask: Can you solve my problem in this session? Or can we do it in two to three sessions?”

Perhaps it’s the Singaporean tendency to want instant results (and more bang for our buck). But as Lexin points out, therapy takes effort, persistence, and trust on both sides.

And when both sides put in the work, it can be an incredibly meaningful experience for everyone involved.

The Hidden Woes of Today’s Youths

Outside the therapy room, the same principle applies: behaviour is a clue, not the whole story.

Entry to young adulthood often means picking up a vice or two. Some youths might hang with the ‘wrong crowd’. Others might start smoking. And lately, K-pods and vapes have emerged as a dangerous new trend.

The truth is, many of these ‘troubled’ youths are misunderstood. They aren’t just acting out willfully. Society, and sometimes even families, tend to focus on outward behaviours—such as defiance, breaking curfews, or engaging in vices—without considering the underlying reasons behind these actions.

Lexin notes that these behaviours often come from feeling misunderstood at home; they’re less acts of defiance than bids for connection. Carmen warns that these coping mechanisms quickly become traps, deepening the struggles they were meant to ease.

All three psychologists I spoke to affirm that one of the most common emerging issues among young clients today is something called anticipatory anxiety.

“Even before they enter the workforce, they start thinking about what the future holds for them,” Lexin tells me.

“With more information online than ever before, these youths are often exposed to constant social comparison–seeing others’ achievements, lifestyles, and apparent successes—which can feel overwhelming for some.”

Carmen sees the same in children barely out of primary school—kids already worried about family finances.

Youths of today indeed have more privileges and choices than previous generations, but this often comes with more expectations to live up to. This generation faces immense pressure to follow a narrowly defined path to success. And for those whose dreams don’t fit, the weight is suffocating, says Isabel.

It’s also important to note that it’s not just the youths who act out that need help; some of them hide behind masks.

“Some seem very okay at the beginning,” Lexin says. “But as the conversation goes a little deeper, you start to realise that they’re struggling with things that no one knows about.”

Isabel often sees youths who feel alone even while surrounded by friends. Their relationships feel shallow; they don’t want to ‘burden’ anyone with their struggles.

The problem is that this is exactly how isolation begins and festers—long after young adulthood.

Beyond the Diagnosis

Society loves slapping labels on troubled young people: Lazy. Weak. Avoidant. But these dismissals mask real pain and may discourage young people from seeking help.

“Even after so many years,” Isabel says, shaking her head, “I’m just like—why is this still going on?”

The reductive picture people tend to paint of ‘troubled’ youth completely ignores their resilience and potential. The psychologists that I spoke to—the people who probably work the closest with these youths—insist that these young people are so much more than their diagnoses or the labels society gives them.

“Actually, there is a lot more to them,” Lexin says. “They have dreams, they have hopes, and sometimes, they just need that little bit more guidance.”

Carmen concurs.

“I wish people would see mental health as part of general health. You shouldn’t wait until it becomes an illness, then do something. The earlier the intervention, the better.”

Of course, none of this work happens in isolation. And it’s not as simple as encouraging youths to seek professional mental health help early, or rethinking the judgments we make of them. The environment shapes every step.

“There are some cases where parents with the best intentions may possess limited understanding of what’s going on with the child—whether because of lack of information or cultural beliefs,” Carmen offers.

“So there are times where we have to work with both the parents, to help them understand what’s going on, and with their child to improve their communication.”

Small Victories

The work of a clinical psychologist is not glamorous. It’s often complex and emotionally demanding, yet deeply impactful—both for the clients and the psychologists themselves.

Not every story ends in success. Isabel recalls a client with severe trauma who wasn’t ready for therapy and eventually dropped out.

“She needed help. I could see that, but she wasn’t particularly ready for therapy… In the end, I didn’t continue seeing her because she dropped out. It’s still a case that stands out in my mind.”

But it’s precisely this unpredictability that makes the small victories matter so much more. All three clinical psychologists tell me that the best moments of their job come in witnessing their clients’ small but life-changing breakthroughs.

Carmen remembers a teenager with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) who couldn’t bring herself to touch her parents.

“They were a very close family, and really affectionate before,” Carmen recalls. “So part of the work was helping them find that again. It was a very tear-jerking moment for everyone, myself included, when the child was able to hug the parents again.”

These little breakthroughs are reminders that change is possible, even if it comes slowly. And maybe, as Isabel muses, that’s enough.

“If I were to dream on a larger scale, if some of my work were to reflect in some very tiny societal shift, I think I’ll be really, really happy.”