All images by Eudea Tan for RICE Media unless stated otherwise.

When the Find Your Folks @ Jalan Besar festival closed down Hamilton Road for a street party, the pre-war carriageway stirred with new life. Skaters soared above the crowd, kickflipping through the music-filled air. Strangers sat together on artfully upcycled benches. Kids and adults alike linger next to friendly games of chess.

Snatches of conversation drifted between stalls—someone admiring a painter at work, another laughing at an old neighbourhood tale—as people met, traded stories, and rediscovered the district through its creative communities.

Besides Find Your Folks, Singapore’s growing calendar of street festivals and pop-up community gatherings—from the Aliwal Urban Arts Festival to the Armenian Street Party—continues to reimagine public spaces as canvases for culture and connection.

They might seem like lighthearted fun—another excuse to eat, shop, and post vibey Instagram Stories. But look closer, and they tell a different story. Amid the food trucks and makeshift stalls, something precious is being rebuilt: a sense of genuine communal belonging in a city that keeps erasing itself.

To this end, these street parties serve as a form of placemaking, a global movement that transforms ordinary or forgotten spaces into memorable places of authentic belonging.

Elsewhere, New York’s High Line transformed an abandoned railway into a linear park that now anchors local businesses, art, and community life. In Seoul, the restoration of the long-buried Cheonggyecheon Stream did more than beautify the city—it reconnected citizens with nature and heritage.

As for Singapore, a city where rising costs, sky-high rents, and stagnant wages have eighty-sixed beloved F&B outlets and arts venues, can street festivals step in to address its unique urban challenges?

What We Lose When We Redevelop Without Care

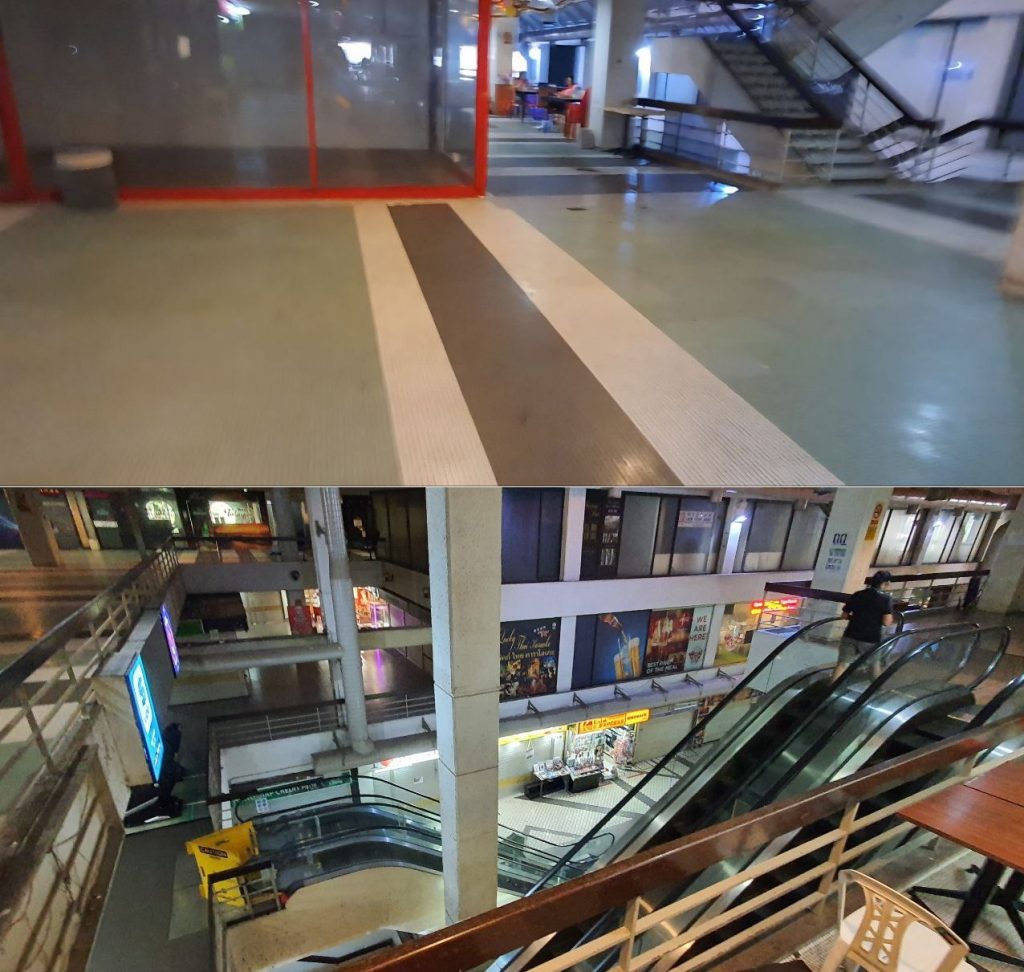

Singapore’s reflex for struggling spaces is demolition. A mall grows quiet? Tear it down. A district loses its shine? Bulldoze and rebuild. When the wrecking ball swings, it flattens not just concrete, but memory.

“We shouldn’t always have to rebuild from ground zero,” says Randy Chan, Principal Architect of Zarch Collaboratives, who has worked on public projects such as i Light Singapore and the Founders’ Memorial.

“Yes, redevelopment is necessary in land-scarce Singapore, but we can afford to be more discerning when demolishing.”

Randy references painful examples, like the old National Library and National Theatre. Personally, I agree.

I remember taking a sentimental walk around Peace Centre last year (which was co-designed by my wife’s late grandfather), absorbing every detail before it was lost to demolition. The year before, I helped my father carry his case files and legal encyclopedias out of Golden Mile Complex. The physical weight of those volumes felt heavier than usual as the fading mix of Thai spices and cigarette smoke hung in the air—a scent I knew I’d never encounter again.

Today, all these disembodied memories survive only in photographs and conversations with friends, which usually start with, “Eh, you remember the time when…”

While some icons, like People’s Park Complex, have dodged plans for total demolition, adjacent landmarks like Pearl Bank Apartments have vanished unceremoniously—leaving Singaporeans with fewer touchstones of identity.

What it does is fuel the perception that our city is forgettable and lacking in tangible heritage.

It’s probably the driving factor behind independent businesses and communities that are increasingly pooling resources to organise festivals that reattach meaning to places. Placemaking initiatives, such as the Singapore Night Festival in the Civic District and the Five Footway Festival in Chinatown, give people a reason to gather again, rekindling the culture that once anchored these streets.

As old venues fade from relevance and homegrown enterprises vanish day by day, Randy sees these challenges as opportunities to add new dimensions to familiar landmarks.

“How do we redesign places with care when the parameters are efficiency? I love that we live in this troubling time, with such an interesting problem to solve.”

Festivals As Anchors of Identity

As placemaking imbues space with meaning to cultivate pride and attachment, it provides a compelling reason to preserve rather than destroy.

“When places are conserved and redesigned for modern use, their residents can proudly proclaim, ‘I’m from Tiong Bahru’ or ‘I’m from Siglap’,” Randy notes. But when neighbourhoods are flattened and rebuilt from scratch, the emotional bonds vanish with them.

Singapore has long pursued a top-down approach to organising its spaces, clustering districts into neat ‘hubs’—medical hub, financial hub, transport hub, arts hub, and so forth. On that note, Randy cautions that culture cannot be manufactured so rigidly. It grows in chance encounters, in the messiness of human participation, wherever it so pleases.

Street festivals, in this sense, are cultural greenhouses of sorts that offer a gentler alternative to Singapore’s “hard reset” of demolition and redevelopment.

By staging inclusive activities—outdoor film screenings, art exhibitions, flea markets—we seed collective memories. These are the locale-driven attachments that draw people back again and again, slowing the erasure of landmarks and creating a sense of continuity across generations.

“When we design cities without people at the centre, we risk losing the soul of a city,” notes Lorenzo Petrillo, founder of placemaking consultancy Lopelab.

Together with his team, they mobilised entrepreneurs, designers, creative collectives, and stakeholders for the Find Your Folks @ Jalan Besar festival as part of Singapore Design Week.

Public reception was downright positive. Cafes, bars, and studios buzzed again—Chye Seng Huat Hardware, Druggists, and The Fashion Pulpit saw new crowds, while the artists from Play!, the chess players of Aliwal Chess Club, and the skaters of Millennial Events found themselves in front of fresh, curious faces.

Lorenzo tells me that he’s been urged to bring the festival back soon. For him, the most rewarding moments were not just the performances, but the unscripted conversations—attendees sharing ideas on how to enrich their own neighbourhoods, and older Singaporeans swapping stories of how Jalan Besar once bustled with trades now half-forgotten.

People weren’t just finding their folks, but also getting acquainted or reacquainted with places they can proudly associate with. And in those shared moments of celebrating Jalan Besar’s genius loci, the invisible walls that divide us quietly came down.

“Besides the buzz around culture and heritage that weekend, I loved seeing foreign labourers spontaneously join locals in the dancing during musical performances,” Lorenzo recalls.

“Connections were being made across people of different social groups. That, to me, is the true value of placemaking.”

Why Placemaking Matters

Singapore is not immune to the global ‘loneliness epidemic’, where hyper-connectivity paradoxically breeds isolation. In Parliament recently, Prime Minister Lawrence Wong flagged how even young Singaporeans are drawn to hikikomori tendencies—retreating indoors, content with only online contact.

Cities from Tokyo to Toronto are grappling with the same dilemma: how do we build connections in an increasingly isolated world?

In Singapore, street festivals are one way to address this search for belonging—but not everyone buys into their magic. Too often, placemaking is reduced to a marketing exercise: more about Instagrammable moments than community. Economic realities play a part too; when people are preoccupied with survival, it’s hard to care about something as intangible as heritage.

And when street activations overlook the spirit of placemaking, events may gloss over social inequalities or prioritise commercial interests, turning public spaces into soulless showcases rather than places for meaningful discourse.

The government, too, has long staged its own placemaking initiatives, from festivals like PARK(ing) Day to PAssionArts Street, further blurring the line between citizen-led culture and top-down design. These efforts have reimagined familiar spaces, but they’ve also raised questions about what kind of participation we want in public life—organic, or orchestrated?

Still, for placemakers like Lorenzo, these street soirées are more than momentary entertainment—they’re seeds that can outlive the events themselves. By centring programmes around storytelling and shared histories, they hope to inspire others to imagine their neighbourhoods differently.

“Long after ‘Find Your Folks’ is gone, I hope memories of our festivals will inspire people to continue those conversations and create their own initiatives,” he says.

Honestly, we don’t need full-blown festivals to reap the benefits of placemaking. A vibrant mural, a well-designed shelter, creative interventions in underused spaces, or even QR-guided self‑tours can ignite curiosity and spark interaction.

For Lorenzo, the greater goal is a shift in mindset: a Singapore where identity and attachment nurture responsibility and pride. It’s a vision of a city where Singaporeans treat streets and squares not as anonymous corridors to rush through, but as shared homes to nurture and enliven.

“When people no longer see public spaces as just transient spaces, but as extensions of their own living rooms, they’ll start caring for them—fixing things, cleaning up, improving them—instead of leaving it all to the government.”

Even if placemaking can turn out imperfect, performative, or unevenly implemented, it remains one of the few mechanisms through which the city’s soul can be felt, claimed, and carried forward by its people.

Towards a More Human City

A city of cookie-cutter malls and smooth infrastructure may run well. But it can also feel bland and alienating.

“If we don’t feel rooted, we might not feel confident,” Lorenzo observes.

“When we feel stressed or down, many of us draw strength from personal identity. But if we aren’t sure who we are, where does that strength come from?”

Creating new festivals might feel redundant, but history tells us otherwise. Our forebears infused vitality into their communities through pasar malams in the heartlands, as well as open-air film screenings and storytelling in Chinatown. Culture, after all, is something built from nothing.

As Randy continues to advise on government projects, he notes that policy is often shaped by real anxieties: how do we build identity in a place that reinvents itself every decade?

His answer: Leave room for incompleteness.

“In Singapore, we like ‘complete’ things—top-down masterplans and zoning that promise results. But it’s okay to be incomplete, because incompleteness allows possibility.”

In those grey spaces between efficiency and imperfection, culture can breathe. And the returns—pride, belonging, happiness—are immeasurable.

“When people don’t feel uprooted, they may enjoy longer, healthier lives, with fewer mental health struggles and even lower crime rates,” Randy reflects.

Just last month, he curated Design For Care at Marina Central, a campaign exploring how spaces can be designed with empathy and human connection at their core. Through showcases, talks, wellness workshops and a two-day music festival, it invited Singaporeans to make memories in new spaces before they grow old.

All this to say that culture is fragile; it is renewed only when people choose to participate. And perhaps the true paradox of Singapore’s progress is this: efficiency may have built our prosperity, but it is the unplanned, imperfect moments of community that make life meaningful.

The question isn’t just what kind of city we want to live in, but what kind of inheritance we leave behind. Buildings will fall and skylines will change, but what matters is what endures between the cracks.

The bunting will come down and the buskers will pack up. Yet if someone remembers dancing with a stranger under Marina Square’s lights, something of Singapore has been saved.