The Price of Tomorrow presented by OCBC is a financial wellness festival held in conjunction with The Financial Coconut and RICE Media to take a holistic, human look at the role of money in our lives.

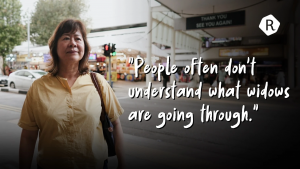

All images by Isaiah Chua for RICE Media.

This might horrify the Type As, but when friends PayNow me after a meal or trip, I don’t check the amount. I simply assume it’s right, much to my fiancé’s bafflement.

I was raised to believe that being calculative about money was a character flaw. To me, talking about money—even something as simple as reminding a friend that they owe me $10 for lunch—feels uncomfortable.

It applies to all other aspects of money with my loved ones. I don’t know how much my brothers earn. Nor do I have any idea how much my parents have saved. In my family, there’s an unspoken consensus: Money comes and goes. As a family, we each contribute as much as we can to get by—no need to overthink things.

The realisation that other families might operate differently came only when I found myself at my fiancé’s family meeting, where his parents coolly discussed their assets and exactly which child was getting what in their will.

It was an openness I couldn’t fathom. Still, for many families and couples in Singapore, it seems like tiptoeing around money talk isn’t uncommon.

A 2024 MoneySmart survey found that 32 percent of Singaporeans find it difficult to discuss finances with their partner. About one in four Singaporeans has had a relationship breakdown due to money disputes.

Clearly, avoiding the topic of money is akin to kicking the can further down the road. But how do you talk about money in a way that builds trust instead of tension?

At a recent The Price of Tomorrow panel, ‘Before I Do: Money, Marriage, and the Plans We Don’t Talk About‘, it became clear that what most Singaporean couples need isn’t purely financial advice—it’s relationship advice.

After all, in Singapore, money is rarely just dollars and cents. It’s emotionally tied to all these other things, like trust and security. Self-worth, even. And ignoring that is where couples trip up.

When More Money Means More Problems

In my parents’ era, money talk was simple because they had none. They met while working minimum-wage jobs at a Chinese restaurant and spent the next few decades working their tails off to provide for three kids.

These days, it’s a little more complicated.

Across ethnic groups here, household incomes have risen over the last decade, driven largely by dual-career couples. The most recent census found that households earning at least $20,000 a month more than doubled from 6.6 per cent in 2010 to 13.9 per cent in 2020.

More of us are getting married later, while we’ve already established our own careers and accumulated our own assets. We’ve also probably taken on obligations, like becoming caregivers for our ageing parents.

Chen Shao Chun, a personal finance content creator, offers his take:

“When we get married, we are not just marrying each other, both financially and non‑financially, we’re marrying each other’s prior lives and future families.”

When he got hitched, one of the topics he had to navigate was how much he and his spouse would contribute to each of their families, he says.

“So the way we actually sat down was—this was extremely un-romantic—but my wife and I said, okay, going into this marriage, we’re going to treat this as a merger and acquisition transaction.”

This meant being completely transparent about each other’s assets, liabilities, and financial obligations, and eventually reaching a compromise.

At the same time, Shao Chun admits that you can’t completely discount emotions from the mix, especially when filial piety comes into play.

Providing financially is proof of a child’s devotion. So when couples ask each other about things like their obligations to parents or inheritance plans, it’s easy for emotions to run high. When that happens, maximising profits becomes less important than being a good partner.

“Do you want to be a husband? Or do you want to be an investor? As an investor, you’ll press [certain numbers] to get a better return. Or do you want to be a husband and realise that there’s only so much influence your spouse has with their family?” he poses to the crowd at 27 Ann Siang.

“So yes, your return on your portfolio might not be as good, but that is the price to pay as a supportive spouse.”

Trust and Transparency

These are tough conversations, to be sure. But not talking about money doesn’t mean your relationship is healthy. It might simply mean the tension hasn’t surfaced yet.

Vasu Menon, Managing Director of Investment Strategy at OCBC, puts it plainly during the panel:

“If you don’t have a conversation… and you go into the marriage, you may have to deal with the conversation when you are married, and then it becomes even more uncomfortable down the road.”

We tend to assume that raising money questions signals distrust. The same way that broaching the topic of a pre-nuptial agreement tends to be misinterpreted as planning for divorce before marriage.

Of course, nothing punctures the romance faster than avoiding money talk for years, then blindsiding your partner with a prenup just before the wedding. But there’s a kind of love in being fully open with each other and in tackling difficult conversations early.

Wong Kai Yun, a senior partner at Dentons Rodyk’s Litigation and Dispute Resolution practice who specialises in matrimonial law matters, suggests reframing the prenup conversation entirely. Rather than “talking about divorce before marriage,” it can be seen as a promise two people make to each other.

“In the Women’s Charter, prenuptial agreements are one of the factors that the court has to take into account,” she said. “In certain circumstances, it would be given significant and even critical weight. It’s a bit like insurance—better than nothing.”

But it’s also a way to start a crucial conversation, Kai Yun insists.

In one recent case she shared, the groom’s parents wanted assurance that the property they willed to their son would remain his. But the prenuptial agreement also included a stipulation that their son’s earnings from the family business would go into a joint account with his future wife. They even deposited some ‘seed money’ into the account to signal their goodwill towards their future daughter-in-law.

“You already know that in your family, these are the things you’ve got to face. So the whole point is to master enough courage together and start that conversation earlier rather than later.”

The Myth of ‘Equal’ Contributions

Part of what makes money conversations with people you love so hard is the illusion that finances can be cleanly separated.

In reality, the money a couple accumulates is the product of joint decisions: Where to live, whether to have children, who prioritises career, and who manages the household.

Trying to split everything strictly down the middle can disproportionately disadvantage women—especially mothers—who still tend to shoulder more unpaid care work.

Vasu shares a personal example: over the past three years, his wife has placed a promising legal career on the back burner to care for their children.

“Contributions to a marriage are never going to be even. Some of it will be financial. Some of it won’t be. My wife gave up her job, and I have benefited from that. How do you value that?”

Ultimately, it comes down to openness. Vasu says there are no secrets between him and his spouse: “She knows what I own. I know what she owns.”

These days, more and more couples are opting to share some money in a joint account, while keeping some money separate. It’s uncommon for couples to merge all their finances, as Vasu and his wife have done.

“For me, our assets are ours… It’s all one. This is a pool of money that the family has,” he adds.

But the key isn’t simply pooling money together and calling it ‘trust’. Rather, it’s talking to each other, acknowledging each other’s contributions, and figuring out what works.

Finding Romance in Financial Planning

It can be daunting to sit down with your partner to talk seriously about money. And perhaps Shao Chun isn’t the best person to offer advice on this—he admits that he and his wife are finance nerds who hold an Annual General Meeting to take stock of their balance sheets.

But for those of us who aren’t as familiar with the finance realm, Shao Chun suggests starting from the basics: “Something as simple as a budget… just talking about budgets with each other will unlock a lot of unconscious biases or spending habits that may help you avoid conflict in the future.”

We often think of money as the root of conflict. But I think avoiding it entirely actually breeds tension.

Early in our relationship, my partner and I started a small savings pool. It wasn’t much, and we didn’t even have a wedding date on the horizon yet. But making that small transfer each month felt like a reaffirmation of our commitment to each other.

Yeah, I was raised to believe that numbers and money shouldn’t define relationships. Turns out, there’s still plenty of romance in knowing you’re building the same life through spreadsheets and shared savings.