Trigger warning: Mentions of suicide.

Image: Xue Qi Ow Yeong / RICE File Photo

On June 1, the police received a distressing call: a 12-year-old girl had locked herself in a room of a flat along Yishun Avenue 11, threatening self-harm.

In response, officers from the Special Operations Command (SOC), the Crisis Negotiation Unit (CNU), and the Singapore Civil Defence Force (SCDF) were swiftly deployed. The SCDF even inflated a safety life air pack at the foot of the block as a precaution.

Photos of the iconic red SOC Tactical Vehicle parked nearby quickly made the rounds online, fuelling debate: Was sending an armoured vehicle necessary for a lone child in crisis?

Fortunately, the situation ended without physical harm. Police gained access to the room, and the girl was apprehended under the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) Act. Under Section 7(1), it is the duty of police officers to apprehend any individual they believe are a danger to themselves or others on the basis of suspected mental disorder.

The operation was technically a ‘success’, but the image of such a response to a child’s mental health emergency struck a nerve. For some members of the public, it felt more like an escalation than a rescue.

To be clear, certain threats, such as if a person is armed or barricaded, justify the activation of specialised units. Understandably, the CNU is under the administrative command of the SOC, which explains the tactical vehicle’s appearance.

Deploying crisis negotiators was undoubtedly the right call, and the fact that no injuries were reported speaks to their effectiveness. When a child’s life hangs in the balance, it’s never easy to choose between swift action and patient, empathetic de-escalation.

Still, questions remain about the optics and ensuing trauma of such scenes—especially for vulnerable individuals in distress.

What We Call Help

“Ideally, the family could have handled the situation without involving the authorities,” opines Kelly*, 26, who speaks from personal experience.

She recalls her own encounter with the police in 2022, during a tough period when stress from school and family pushed her to the ledge of an HDB block.

“A passerby must have seen me and called the police,” she says. “They came running up the stairs and pulled me away. I was examined by caring paramedics, but personally, the police felt cold. And being taken to IMH (Institute of Mental Health) in the back of a police car felt humiliating.”

Since May 2019, suicide attempts have been decriminalised in Singapore. The repeal of Section 309 of the Penal Code marked a shift in how society views suicide—from a punishable offence to a symptom of mental distress that calls for care. Police are now trained to refer individuals for help, not punishment.

Yet, lived experiences like Kelly’s suggest that the system could still work on its nuance and empathy.

“I understand they had to act fast,“ Kelly says. “My experience was traumatic—not because they stopped me, but because of how procedural it felt.”

Today, she supports stronger mental health interventions, but urges more compassion in the way first responders engage with vulnerable individuals.

“I think many officers want to help. But over time, maybe they get jaded from having to deal with these situations frequently. Still, we need to remember that for the person in crisis, this is likely the worst moment of their life—and how you treat them in that moment matters.”

How, then, should first responders respond? And what can we do when someone in distress turns to us first?

“Just be there, not as an authority figure but as a fellow human being,” advises Arjuna, 30, who intervened twice to prevent a close friend from committing suicide.

In one instance, he stopped her from swallowing a bottle of pills and let her cry it out while punching a pillow he was holding.

“She was going through something a lot darker than what her friends and family could see.”

And if you ever find yourself in his shoes, he advises creating a safe space for that individual.

“Because in the pits of their despair, their first instinct is to feel extremely alone. Once they can see some light, they will feel some purpose.”

Between Care and Control

There may be a way for such escalation to be avoided, and it starts with mental health literacy.

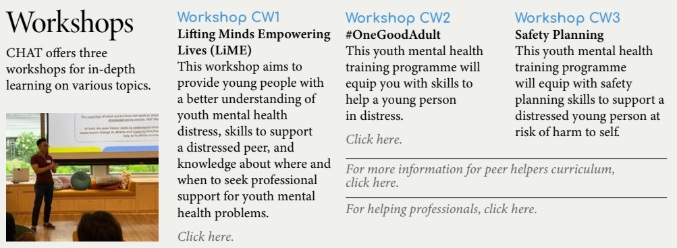

The landscape is starting to shift with the rise of accessible services like CHAT, which advocate for greater access to both in-person and online counselling, alongside broader awareness of safety planning skills.

CHAT runs a variety of programmes that teach people how to support youths in crisis, and they aren’t the only ones providing these workshops. As mental health takes centre stage in shaping our future, resources like these are more vital than ever.

It’s a promising step forward, though much work remains. If friends and loved ones are armed with knowledge, perhaps fewer emergencies would escalate to the point of having to call the cops.

While some urgent cases do require immediate intervention from the authorities, the focus should be on prioritising de-escalation and involving mental health professionals swiftly, writes Dr Jared Ng, Senior Consultant and Medical Director at Connections MindHealth, in a CNA op-ed last year.

“Mental health professionals and law enforcement officers have a responsibility to work together to ensure the best possible outcomes… Only then can we ensure both public safety and the compassionate treatment of those in mental health crises.”

Crisis Response is More Than Just Showing Up

Incidents like these force us to examine whether we’re meeting mental health crises with care or control. While safety is paramount, and every case brings its own risks, the need for sensitivity among first responders is clear, which can be achieved through closer cross-agency collaboration.

In a post-criminalisation era, our institutions must catch up not just with policy, but with practice, ensuring interventions are not only effective, but humane.

Can we evolve beyond a societal framework rooted in reward and punishment towards one that centres dignity? A person in distress needs delicate care, not deterrent force.

Empathy is not a soft skill. It’s a form of strength that can be trained, especially in high-pressure situations where lives hang in the balance. If we approach mental health episodes like enforcement operations, we could risk alienating the very people we’re trying to protect.

The 12-year-old girl in Yishun may never forget the sight of that big red truck, the uniformed officers, and the overwhelming machinery meant to keep her safe. Neither should we.

*Name has been changed for anonymity

Helplines in Singapore

Samaritans of Singapore (SOS) Crisis Helpline

Call: 1-767

Institute of Mental Health Helpline

Call: 6389 2222

National Care Hotline

Call: 1800 202 6868

Singapore Association of Mental Health (Toll-Free Counselling Hotline)

Call: 1800 283 7019

ec2 online counselling

Visit: www.ec2.sg

CHAT

Visit: www.chat.mentalhealth.sg