Top image: Amanda Heng, Every Step Counts (2019). A Singapore Biennale 2019 commission.

These are criticisms typically lobbied at our nation. I am guilty of this as well. When I was a hot, strapping lad of 18 and deciding which university I wanted to enrol in, I didn’t even give our local universities a second of consideration. I wanted to get as far away from Singapore as I could.

I still do. I’m sick of how our landmarks like Rochor Centre are mercilessly torn down to make way for something utilitarian like a freaking highway or Pearl Bank Apartments for yet another soulless steel-and-glass condominium. I’m tired of being confronted with the same cookie-cutter malls with the requisite Uniqlo, Golden Village, Ichiban Boshi.

I want to live in a country where common spaces are cherished. Where individuals matter. Where the new does not always supersede the old.

“The crane.”

“Why?”

“You see it everywhere because things are always under construction.”

Someone once told me this joke. It’s a bad joke. But it is true.

And it is part of why Singapore has an identity crisis. When buildings—and all the memories and emotions they have lovingly nursed within their spaces—suddenly turn into a flattened landscape one day, barricaded by signs warning us to KEEP OUT, how can we not feel as if we have lost an integral part, not just of ourselves but of our nation too?

And we Singaporeans have carved an identity from the demolition of our former memories. Out of this rubble we have reclaimed the ubiquitous danger sign adorning construction sites across the island: it is now splashed on tee-shirts and souvenirs, implicitly proclaiming that this constant demolition is, ironically, our national character.

In this way, our attempts at redefining what Singapore means to us allow the Singapore spirit to soar in a way the cranes cannot.

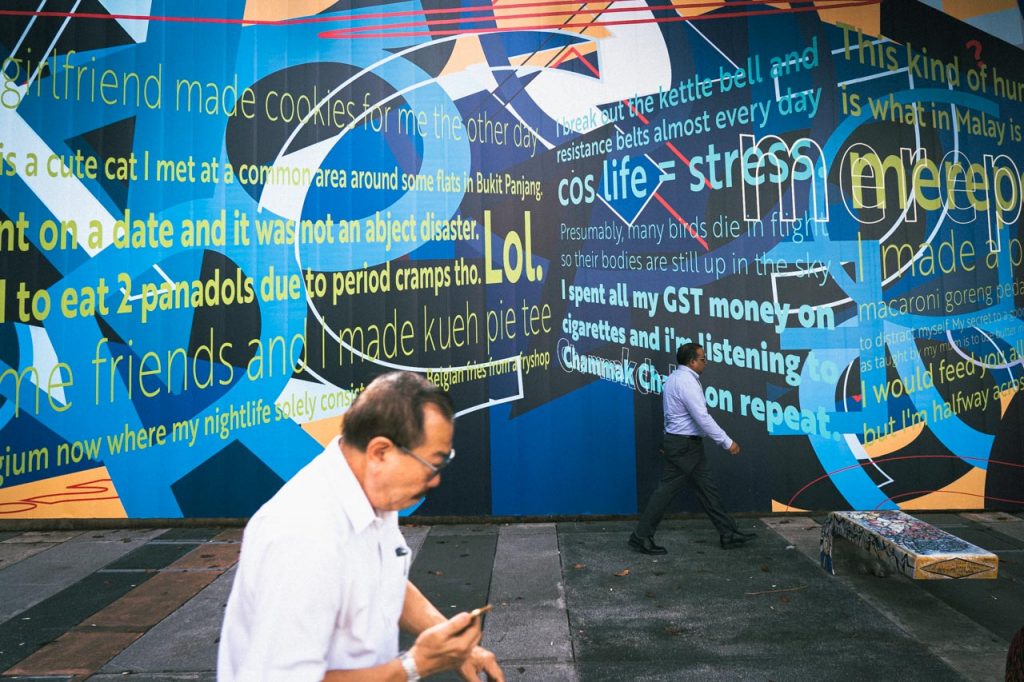

It does so by turning the construction hoardings around the SAM at 8Q into a riotous piece of art that celebrates our everyday life—on it are extracts from WhatsApp chats with her friends.

“We have so many birds around, but I rarely see their carcasses. WHERE ARE THE DEAD BIRDS?!?!?! Presumably, many birds die in flight so their bodies are still up in the sky,” goes one thread of conversation.

I don’t know what Pooja really wants her artwork to say. It’s thought-provoking, for sure. And like all great art, it changed me irrevocably. Before viewing Coping Mechanisms, I had not thought about pigeon carcasses at all, but now I can’t get them out of my head.

On a more serious note, despite not fully understanding the message of the artwork, it did make me reflect on my relationship with our city’s obsession with urban renewal. As much as I feel that with each demolition, we are losing some part of our city permanently, the WhatsApp conversation on the construction hoardings reminds me that our voices will fill these spaces once again.

Public art, the argument goes, takes art out of stuffy museums, which liberates it from being a “thing” to be seen and traded by an exclusive group of people. When created and displayed in the open, it welcomes passers-by who might be on their way to … wherever it is human beings who have a life outside the office go.

More crucially, most public art respond in some way to the place where it is displayed. Thus, it invites contemplation not as an art object divorced from its context and surroundings—e.g. the way we experience a Chinese painting of peony blossoms in a British gallery—but as a piece of work that interacts with and interrogates the space it is in.

What this means, practically, is that such artwork makes us view the places we walk past every day with new eyes. Locations that once looked tired and worn out attain a new life.

We realise we have grown jaded of the city because we have stopped seeing it.

I stopped and stared at them for a bit because they looked pretty. The leaves had an alluring, iridescent sheen, like an oil slick dancing on the sea. I admired them for a bit, marvelling at the way their roots crawled into the crevices of the bricks.

Then I left, still thinking they were leaves.

They were not leaves. They were, I found out later, leftover paint and material from the artist.

I don’t have much to say about the art except that it looked like really pretty leaves to me.

But that, perhaps, is the point of the piece, I think. As long as it made me stop and consider the space carefully, does it matter if it was Art or really just a bunch of plant matter?

Maybe I was looking for the city’s soul in all the wrong places. Sure, it inheres in heritage buildings, ground-up community movements, art enclaves … but Far from Home (Meeting Place) reminded me that it also exists in homes and in the mundane, like a sapling fighting for life between the tiles of a HDB carpark.

In the same way, public installations are more than just interactions with the tactile characteristics—e.g. its texture, temperature, height—of a space. Without light, sound, or people, a space is just … literally what the word says: a space.

It’s pretty. People will take photographs of it and post them on Instagram. It’s the sort of art that will make people go, “Wow, look at how vibrant Singapore’s spaces are.” Then they will walk away and forget about it.

I know this because that’s me, every Singapore Night Festival and Singapore Biennale and whatever art festival Singapore has seemingly throughout the year nowadays. And then I complain about Singapore’s art scene being sterile.

This epiphany struck me because the sun was very hot. So I climbed under Lani’s artwork, seeking shade. It made for an excellent umbrella.

Inside, I found solace, but was also unexpectedly transported to a world of pure sound. Catching the muggy breeze of the day, the capiz shells started to whisper to me, so I closed my eyes, trying to catch their words. I felt … peaceful? It was a strange feeling. I’m not usually a calm person. Nor could I believe I was still in Singapore and sitting on the lawn of the National Museum.

When I thought things couldn’t get any weirder, a child, seemingly oblivious to my presence, wobbled his way in and plopped himself down beside me.

There we sat, silently, listening to the song of the shells, as if it were the most natural thing to do. Which, in retrospect, I suppose it is—this is after all what Lani, the artist, intended her artwork to do. It was designed less as an object than as a space, an aural experience, that encourages people to interact with the work and with each other.

Was this place, this feeling, here all along? Was all it took an artwork to foreground that sense of peace and solidarity that can be found in the busy, cold heart of the city?

But if I’ve lived in Paris all my life, that charming boulangerie with baguettes sticking out of baskets will become just another BreadTalk to me.

Maybe that’s the problem with me. I seek Singapore’s soul in monuments; I think malls evict communities. But I’ve been looking in the wrong places—or not looking at all.

A city’s soul might manifest in the stupid WhatsApp texts I share with my friends. The quiet spaces of the city that refresh me. Or something as basic as a tree that, unexpectedly, blazes into bloom at the start of the monsoon season.

I just needed someone, or something, to say, “Hey, look here. What you’re looking for has been here all along.”

What do you think is the soul of Singapore? Tell us your thoughts at community@ricemedia.co.